Okay, let's dim the lights and slide this tape in. The tracking might be a little fuzzy at first, but the dread? That comes through crystal clear. Forget gentle ghosts or bumps in the night; sometimes the most terrifying thing is the void right next to you, the unseen malice. Paul Verhoeven's Hollow Man (2000) arrived just as the millennium turned, feeling like a technologically supercharged, mean-spirited echo of classic Universal horror, dragged kicking and screaming into the digital age. It asks a simple question – what would you do if you were invisible? – and answers it with deeply unsettling cynicism.

### The Unseen Edge of Madness

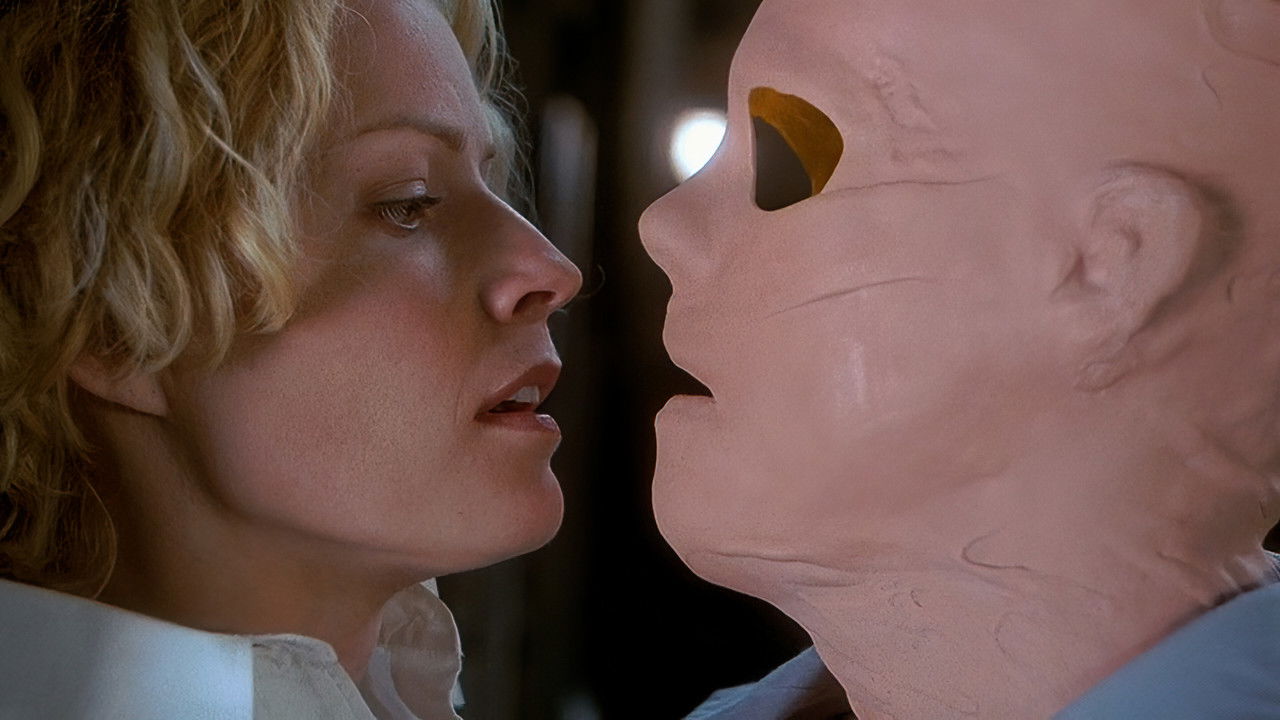

Right from the start, there's a cold, clinical feeling permeating the underground lab where Dr. Sebastian Caine (Kevin Bacon) and his team, including ex-lover Linda McKay (Elisabeth Shue) and colleague Matt Kensington (Josh Brolin), push the boundaries of science. Verhoeven, never one to shy away from the uncomfortable – this is the man who gave us the brutal satire of RoboCop (1987) and the fascistic spectacle of Starship Troopers (1997) – doesn't frame Caine's breakthrough as heroic. It’s obsessive, reckless, fuelled by ego. When Caine ignores protocol and makes himself the first human test subject, the film doesn't just become about invisibility; it becomes about the terrifying stripping away of inhibition, morality, and humanity itself. That slow, agonizing transformation sequence, layer by visceral layer? It wasn't just groundbreaking effects; it was a visual metaphor for a soul turning monstrous.

### A Spectacle of Skin and Sinew

Let’s talk about those effects, because back in 2000, they were absolutely jaw-dropping. Forget the slightly rubbery CGI monsters of earlier years; Hollow Man earned its Academy Award nomination for Best Visual Effects. The painstaking work by Sony Pictures Imageworks, blending CGI with practical elements, created truly unforgettable moments. Remember seeing the outline formed by steam, or rain, or blood? Or that horrifying sequence where Caine’s musculature and veins become visible before vanishing again? It felt disturbingly real, a technological marvel used to depict grotesque violation. Achieving this wasn't easy. Kevin Bacon spent countless uncomfortable hours encased in green suits, latex masks painted black, green, or blue inside (to reduce light reflection), and contact lenses, effectively performing blind for many scenes. He later called the experience isolating and frustrating, which perhaps inadvertently channelled perfectly into Caine’s increasingly detached and hostile psyche. The sheer technical hurdle of making someone convincingly disappear on screen, interacting with the environment, was immense, requiring innovative motion capture and rendering techniques that pushed the envelope.

### Bacon's Brilliant Breakdown

While the effects were the draw, it's Kevin Bacon's fearless performance that anchors the horror. Caine isn't just a scientist gone wrong; he becomes a predator, an entitled voyeur who quickly escalates to far worse. Bacon throws himself into the role with chilling conviction, his disembodied voice dripping with menace, his physical presence (when visible, or implied) radiating danger. He makes Caine utterly despicable, yet somehow magnetic in his depravity. Does anyone else recall feeling genuinely unnerved by his casual cruelty long before the outright violence begins? Elisabeth Shue and Josh Brolin do solid work as the increasingly desperate targets of Caine's invisible wrath, grounding the escalating chaos with palpable fear and determination. Their struggle against an enemy they often can't even see generates considerable tension, especially within the claustrophobic confines of the locked-down lab.

### Verhoeven's Uncompromising Glare

This isn't a feel-good sci-fi adventure. True to form, Paul Verhoeven embraces the nastiness. The film reportedly cost a hefty $95 million – a significant sum for an R-rated horror/thriller back then – and Verhoeven allegedly clashed with the studio, resisting pressure to tone down the darker elements and violence for a potentially more lucrative PG-13 rating. Thank goodness he held firm. The film's power lies in its willingness to explore the ugliest impulses invisibility might unleash. From voyeurism and sexual assault to brutal, calculated murder, Hollow Man doesn't flinch. It's a sleek, often brutal thriller that uses its high-concept premise not just for spectacle, but to expose a chilling darkness within its protagonist. Andrew W. Marlowe (who penned Air Force One (1997)) provided the initial script, but Verhoeven's cynical fingerprints are all over the final, grim product.

### The Lingering Chill

Hollow Man arrived a little late for the true VHS heyday, hitting screens as DVDs were rapidly taking over. Yet, it feels spiritually connected to the ambitious, often boundary-pushing R-rated genre films of the late 80s and 90s. It’s a studio picture with sharp teeth, impressive technical prowess, and a willingness to be genuinely unpleasant. While perhaps not as thematically rich as some of Verhoeven’s earlier work, and maybe the supporting characters could have used more depth, its central horror concept, fuelled by Bacon’s performance and those state-of-the-art (for the time) effects, remains potent. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the most terrifying monsters aren't aliens or creatures, but the darkness lurking unseen within ourselves, just waiting for the constraints to disappear.

Rating: 7/10

Justification: The groundbreaking visual effects (for 2000) and Kevin Bacon's chillingly committed performance are undeniable strengths. Verhoeven delivers intense, often brutal thrills with his signature cynical edge. However, the supporting characters feel somewhat underdeveloped, and the script occasionally relies more on shock value than narrative depth. Still, it's a remarkably effective and unsettling slice of sci-fi horror that holds up as a visceral experience.

Final Thought: Watching Hollow Man today is a potent reminder of that late-90s/early-2000s moment when CGI was becoming truly convincing, used here not just for wonder, but for deeply uncomfortable, skin-crawling horror. It might not be subtle, but its central terror – the violation you can't see coming – still leaves a residue of unease.