For decades, it existed more as myth than reality, a holy grail whispered about in martial arts circles and home video forums. We all knew Bruce Lee had been filming something ambitious, something deeply personal called The Game of Death, when he tragically left us far too soon in 1973. We’d seen snippets, bizarrely repurposed and padded out in the questionable 1978 film of the same name. But the real footage, Lee’s actual vision? That felt lost to time, another layer to the legend’s mystique. Then, in 2000, came Bruce Lee: A Warrior's Journey, a documentary that felt less like a film and more like an archaeological discovery finally brought into the light.

Beyond the Exploitation

Let's be honest, the 1978 Game of Death was… something. A cash-in cobbled together with awkward body doubles, flimsy plotting, and mere minutes of genuine Bruce Lee footage, often used out of context. It was a fixture on video store shelves, sure, instantly recognizable by its iconic poster, but it always felt profoundly wrong, a disservice to the man himself. What A Warrior's Journey, meticulously helmed by Bruce Lee historian John Little, achieves is nothing short of restoration – not just of film reels, but of artistic intent. Little, drawing on extensive research and unprecedented access granted by Lee's estate, including Linda Lee Cadwell, set out not just to show the lost footage, but to place it within the context of Lee's evolving philosophy, Jeet Kune Do, and his vision for what martial arts cinema could be.

Unearthing the Pagoda

The heart of the documentary, and the reason it sent reverberations through the fan community, is the presentation of roughly 40 minutes of Lee's original, uncut footage intended for the climax of The Game of Death. Discovered tucked away in the Golden Harvest archives, these reels contained the legendary multi-level pagoda sequence, filmed by Lee himself. Little painstakingly assembled this material according to Lee's own detailed notes and script outlines, giving us the most complete and coherent version of Lee's concept possible. And seeing it, truly seeing it as intended? It's breathtaking.

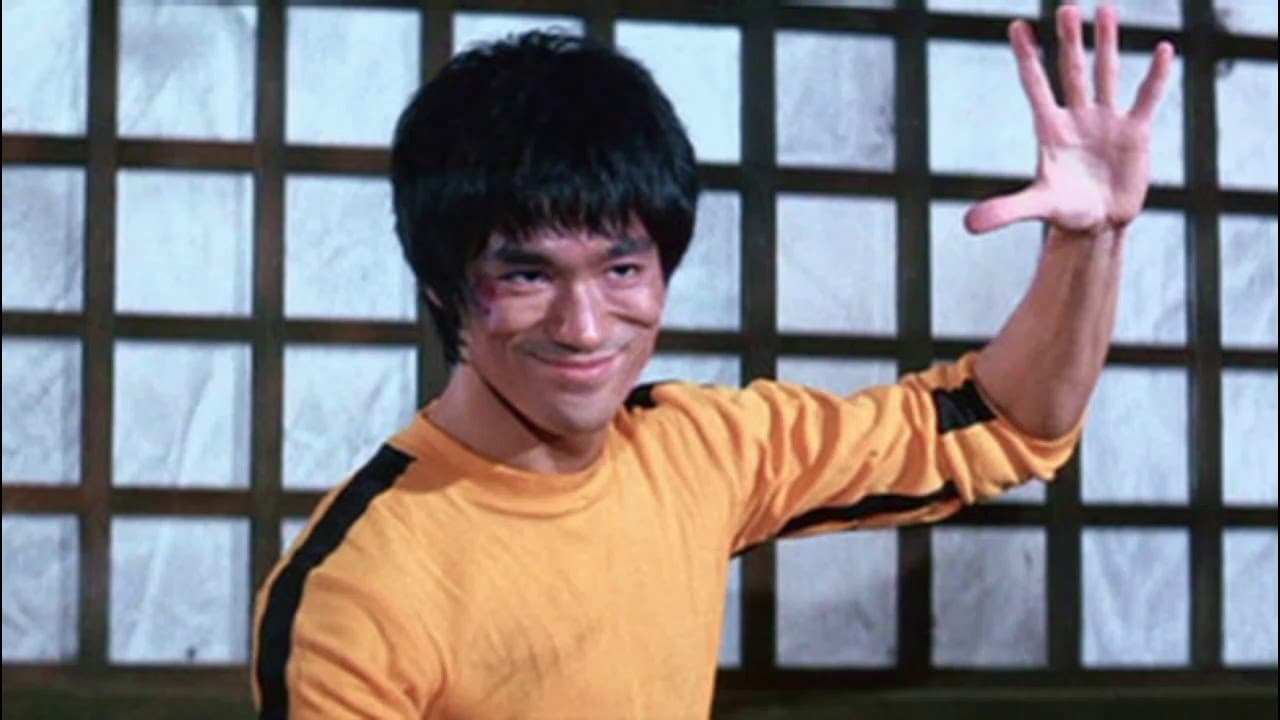

Forget the clumsy edits of '78. Here, we witness Lee, clad in that now-legendary yellow-and-black tracksuit (a practical choice, apparently, as it showed impact marks well, but now forever iconic), ascending the pagoda, facing masters of different styles on each floor. The choreography is fluid, dynamic, and deeply rooted in Lee’s Jeet Kune Do principles of simplicity, directness, and adaptability. The fights against longtime student and friend Dan Inosanto (master of Filipino Kali), Hapkido Grandmaster Ji Han-jae, and finally, the towering Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (a student and friend of Lee's), are presented with a clarity and length previously unseen. There’s a raw intensity here, a sense of philosophical exploration through combat, that the '78 film completely missed. It wasn't just about winning; it was about demonstrating the limitations of rigid, classical styles against JKD’s formless form.

A Glimpse into the Mind

A Warrior's Journey does more than just showcase the fights. It uses interviews, Lee's own writings, and contextual narration to frame the pagoda sequence as the ultimate expression of his martial philosophy. We learn about the symbolism Lee intended – each level representing a different challenge, a different aspect of martial arts dogma to be overcome. The documentary takes pains to present Lee not just as an action star, but as a thinker, an innovator constantly pushing boundaries. Hearing Linda Lee Cadwell speak about his passion for this project adds a layer of poignant intimacy. It becomes clear this wasn't just another movie for Lee; it was intended as a deeply personal statement. One fascinating tidbit often discussed is how Lee specifically chose opponents like Abdul-Jabbar, not just for the visual David-and-Goliath dynamic, but because their skills represented specific challenges he wanted his character (and philosophy) to overcome.

More Than Just Lost Footage

Watching this documentary, especially for those of us who grew up renting battered VHS copies of Enter the Dragon (1973) or even the '78 Game of Death, feels like solving a long-standing puzzle. It provides closure, correcting the historical record and offering a profound sense of "what might have been." The quality of the recovered footage is remarkable, showcasing Lee’s incredible physical prowess and screen presence near the peak of his powers. Seeing the unedited takes, the moments between action, even Lee directing his co-stars, adds a layer of humanity often lost in the tightly-cut final products of his finished films. It connects us to the process, the journey of creation, which feels incredibly valuable.

Does it fully reconstruct The Game of Death? No, that remains impossible. Too much was left unfilmed. But what John Little achieved was monumental: rescuing Lee's core vision for the film's climax from obscurity and presenting it with the respect and context it deserved. It serves as both a vital historical document and a moving tribute.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the documentary's immense historical significance for Bruce Lee fans and martial arts cinema enthusiasts. It expertly contextualizes and presents the recovered footage, finally allowing Lee's intended vision for the Game of Death climax to be understood and appreciated. While inherently incomplete due to the source material, A Warrior's Journey achieves its goal brilliantly, offering a respectful, insightful, and often thrilling look at a legend's final, unfinished masterpiece. It doesn't just show footage; it restores a piece of Bruce Lee's soul.

For anyone who ever wondered about the real Game of Death, this isn't just recommended viewing; it feels like essential viewing – a piece of cinematic history finally brought home.