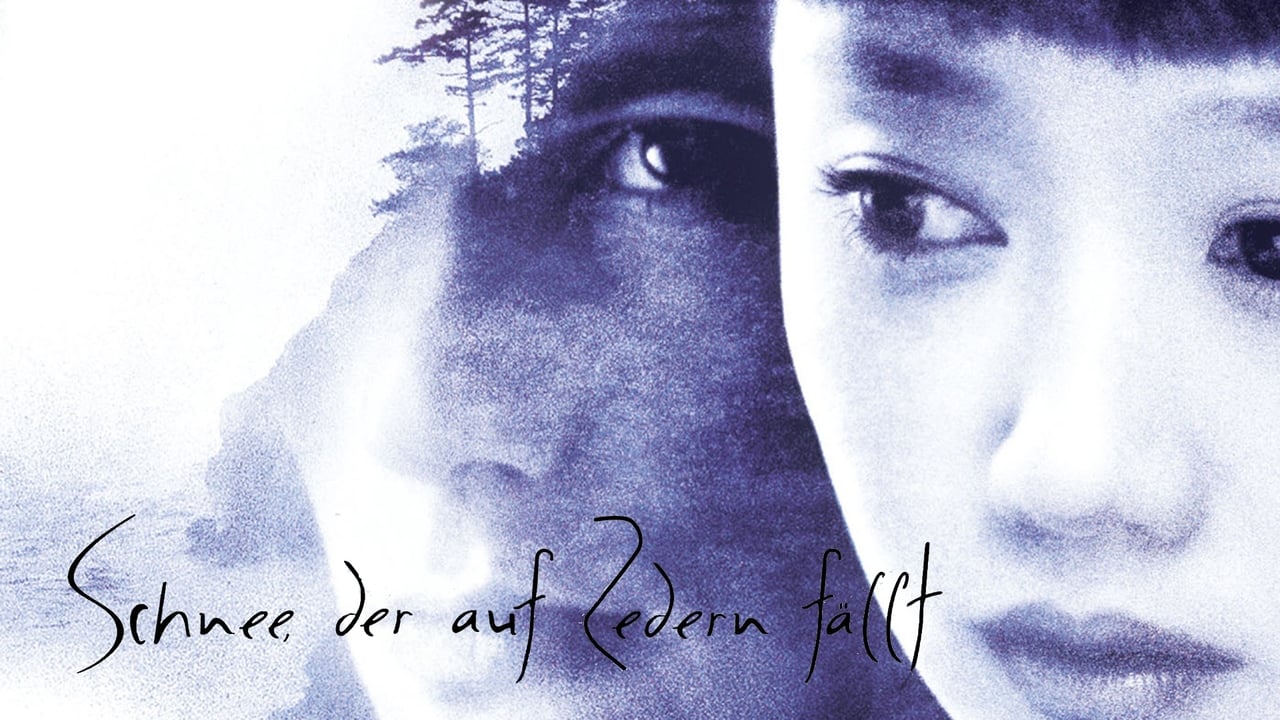

There's a certain hush that falls over Scott Hicks' Snow Falling on Cedars (1999), a quiet that permeates the screen much like the titular snow blankets the fictional San Piedro Island in the Pacific Northwest of 1954. It’s not the silence of emptiness, but the weighted quiet of unspoken histories, simmering prejudices, and memories held captive like breath in the winter air. Watching it again, years after first sliding that VHS tape into the VCR – likely rented alongside louder, more immediately gratifying fare – the film's deliberate pace and somber beauty feel even more pronounced, a stark contrast to so much that clamored for attention then, and now. It asks us to lean in, to listen to the whispers beneath the courtroom drama.

Beneath the Surface of a Small Town Trial

Based on David Guterson's celebrated novel, the film centers on the murder trial of Kazuo Miyamoto (Rick Yune), a Japanese-American fisherman accused of killing a fellow islander, Carl Heine. Reporting on the trial is Ishmael Chambers (Ethan Hawke), the editor of the local newspaper, a man irrevocably bound to the accused's wife, Hatsue (Youki Kudoh), by a poignant, secret adolescent love affair tragically interrupted by World War II and the shameful internment of Japanese-American citizens. The trial itself becomes a crucible, forcing the community – and Ishmael – to confront the ghosts of the past, the deep-seated racism exacerbated by the war, and the complex, often painful nature of truth.

Hicks, who had previously captured lightning in a bottle with the vibrant Shine (1996), here adopts a far more meditative approach. The narrative weaves seamlessly between the stark courtroom proceedings of 1954 and the sun-dappled, yet fragile, memories of the 1940s. This isn't merely a flashback device; it’s central to the film’s thesis. How do past traumas – personal and collective – infect the present? Can objectivity exist when viewed through the lens of deeply ingrained prejudice and unresolved heartbreak? The film doesn't offer easy answers, instead immersing us in the melancholic atmosphere of a community struggling to reconcile its ideals with its actions.

A Canvas of Cold Beauty and Quiet Pain

Visually, Snow Falling on Cedars is breathtaking. Cinematographer Robert Richardson (a frequent collaborator with Oliver Stone and Quentin Tarantino) earned a well-deserved Oscar nomination for his work here. He paints with a palette of muted blues, grays, and whites, capturing the oppressive beauty of the snow-laden landscape. The dampness feels almost tangible, the chill seeping into the very bones of the story. From the fog-shrouded waters to the claustrophobic intimacy of the courtroom, every frame is meticulously composed, enhancing the film's themes of isolation, hidden truths, and the suffocating weight of history. It’s the kind of cinematography that truly benefited from the largest screen you could find back then, though even on a fuzzy CRT, its power was undeniable. Filming largely in British Columbia and Washington state, the production reportedly battled actual challenging weather, an effort that pays dividends in the film's authentic, lived-in atmosphere.

Performances Etched in Restraint

The performances are keyed to the film's understated tone. Ethan Hawke, then solidifying his transition to more serious adult roles after Gen X touchstones like Reality Bites (1994), carries the film's emotional core as Ishmael. His is a performance of quiet observation and simmering resentment, a man physically and emotionally scarred by the war and his lost love. He conveys Ishmael’s internal conflict – his journalistic duty versus his personal history – with subtle glances and a pervasive sense of weariness.

Youki Kudoh is luminous as Hatsue, embodying a quiet strength and dignity amidst the suspicion and her own complicated feelings. The scenes depicting her youthful romance with Ishmael possess a fragile tenderness that makes their later distance all the more resonant. And then there’s the legendary Max von Sydow as Nels Gudmundsson, Kazuo’s defense attorney. Von Sydow, whose screen presence always commanded attention since his iconic work with Ingmar Bergman, brings immense gravitas to the role. His closing argument isn't pyrotechnics; it's a deeply felt appeal to reason and conscience, delivered with the weary wisdom of a man who understands the deep roots of prejudice all too well.

Echoes in the Silence

Despite its literary pedigree, acclaimed director, talented cast, and stunning visuals, Snow Falling on Cedars wasn't a box office sensation (grossing around $24 million worldwide against a $35 million budget). Perhaps its deliberate pacing and somber themes were a difficult sell in the late 90s marketplace. It demands patience, asking the viewer to absorb its atmosphere and contemplate its uncomfortable questions about justice, racism, and the persistence of memory. It doesn’t offer the easy catharsis of a typical courtroom thriller; its resolutions are quieter, more internal.

What lingers long after the credits roll isn't necessarily the intricate plot of the murder mystery, but the pervasive mood – the chill of the snow, the weight of unspoken words, the haunting beauty of a love lost to time and prejudice. It’s a film that reminds us how easily fear and resentment can curdle a community, a theme that sadly remains perpetually relevant. Doesn't the struggle to see past prejudice, to truly understand the 'other,' feel as urgent now as it did in post-war America?

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's exceptional craftsmanship, particularly its evocative cinematography and restrained performances, and its willingness to tackle profound themes with nuance and sensitivity. Its deliberate pace might test some viewers, preventing a higher score, but for those willing to immerse themselves in its melancholic world, Snow Falling on Cedars offers a rich, rewarding, and deeply felt cinematic experience that stands apart from the louder offerings of its era. It’s a film that settles over you slowly, thoughtfully, much like the snow itself.