Some films arrive shrouded in whispers, their reputations preceding them like a chilling fog rolling in off the water. Boxing Helena wasn't just whispered about in 1993; it was shouted about, argued over, sued over. Long before the tape ever slid into my VCR – likely rented from the 'New Releases' wall purely out of morbid curiosity fueled by headlines – the story of its creation was almost as bizarre as the psychosexual fairy tale it spun. It promised something transgressive, something dangerous. Did it deliver? Well, that requires a descent into the ornate cage of its narrative.

An Uncomfortable Proposition

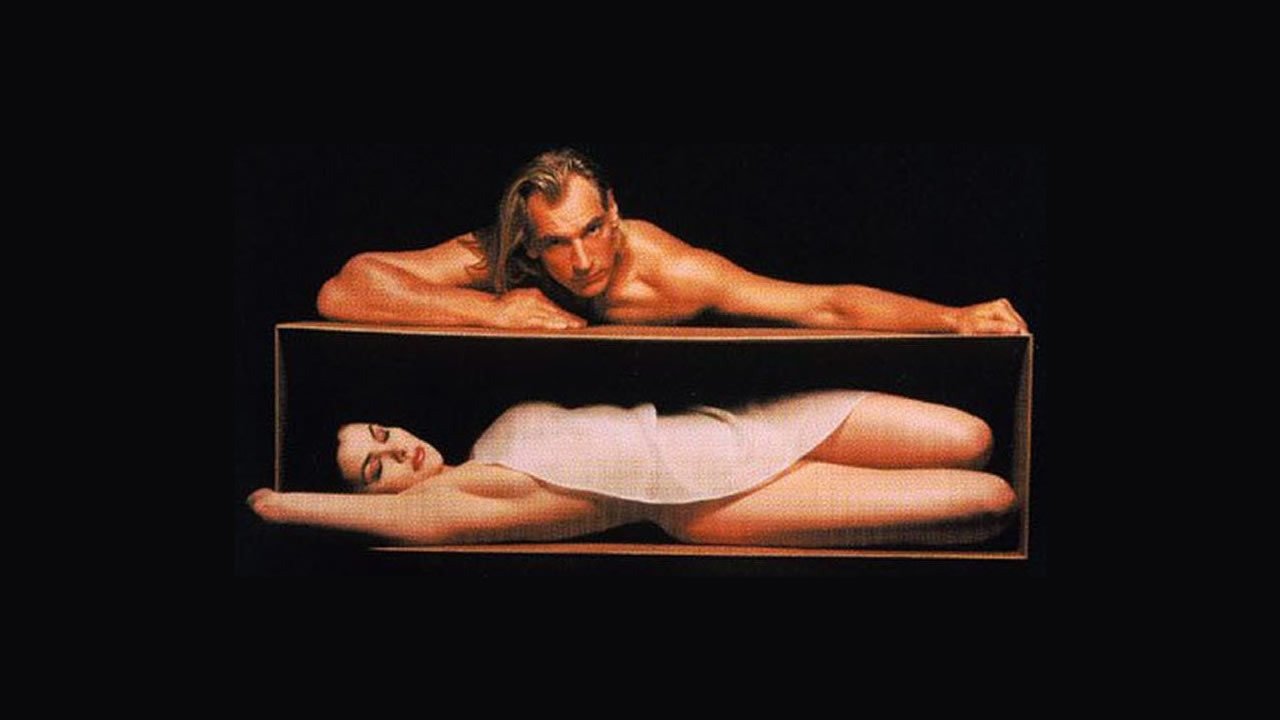

The premise alone is enough to make your skin crawl. Dr. Nick Cavanaugh (Julian Sands, perfectly cast for his unnerving intensity honed in films like Warlock), a brilliant surgeon haunted by his past and crippled by obsessive desire, fixates on the beautiful but disdainful Helena (Sherilyn Fenn, then riding high from Twin Peaks). After she rejects him one final, brutal time and is subsequently involved in a horrific accident near his isolated mansion, Nick makes a decision so grotesque it still feels shocking: he amputates her legs, and later her arms, keeping her captive – a living Venus de Milo, utterly dependent on his care. It’s a setup steeped in dread, promising a deep dive into obsession, control, and the male gaze turned monstrous.

Gilded Cage, Hollow Center?

Director Jennifer Lynch (daughter of the master of surreal dread, David Lynch) was just 24 when she helmed this, her debut feature. The film looks sumptuous in a decaying sort of way. The production design crafts a world that feels both opulent and suffocating, Nick’s mansion a lonely palace filled with classical art and surgical precision, mirroring his fractured psyche. There's an undeniable atmosphere here – a slow, deliberate pace emphasizing Helena's confinement and Nick's meticulous, disturbing ministrations. The score often drifts into unsettling ambient territory, punctuated by classical pieces that feel ironically applied to the unfolding horror. Yet, for all its atmospheric potential, the film often feels strangely inert. The tension relies heavily on the inherent horror of the situation, but the psychological exploration sometimes feels surface-level, the dialogue occasionally tipping into stilted melodrama. Sherilyn Fenn, trapped physically and perhaps narratively, does her best to convey rage and despair, but the script gives her limited avenues beyond defiance and vulnerability.

Retro Fun Facts: The Making of a Maelstrom

You can't discuss Boxing Helena without mentioning the pre-production chaos that became Hollywood legend. The role of Helena was a hot potato few wanted to hold. Kim Basinger famously accepted the role, then backed out, leading to a highly publicized lawsuit by production company Main Line Pictures that resulted in an $8.1 million judgment against her (later overturned and settled out of court). Before Fenn bravely stepped in, Madonna was also attached, only to depart as well. This legal turmoil overshadowed the film itself, generating immense notoriety but perhaps setting expectations impossibly high for what was ultimately a relatively low-budget ($2 million) arthouse horror piece. It certainly didn't help its box office prospects, barely recouping its budget with a $1.8 million domestic gross. Even Bill Paxton appears in a somewhat thankless role as Ray, a former lover of Helena’s, offering a brief glimpse of the outside world she’s lost. Lynch herself reportedly faced immense pressure, not just from the lawsuits but from delivering on the provocative premise under the inevitable comparisons to her father's work. Did the off-screen drama inadvertently become more compelling than the on-screen story? For many, the answer was yes.

Body Horror or Broken Fairy Tale?

The film walks a precarious line. Is it a chilling examination of obsessive love and the ultimate act of objectification? Or is it an exercise in shock value that doesn't quite connect emotionally? The practical effects depicting Helena's state are handled with a degree of restraint – less graphic gore, more unsettling implication – which aligns with the film's arthouse aspirations. Yet, the central conceit remains deeply disturbing. Some critics at the time lambasted it as misogynistic and exploitative, while others saw a dark fable about control and vulnerability. Watching it now, through the lens of decades past, its flaws are perhaps more apparent – the pacing lags, the psychological insights feel underdeveloped. But there's still something undeniably bold about it, a willingness to venture into truly uncomfortable territory that few mainstream films would dare. Remember how certain films just felt dangerous to rent back then, like you were accessing forbidden knowledge? Boxing Helena definitely carried that aura.

Spoiler Alert! (Regarding the Ending)

The film's infamous twist ending – revealing the entire horrific scenario to be Nick's dream/fantasy following Helena's actual accident (where she survives relatively unscathed) – remains deeply divisive. Does it undercut the preceding horror, rendering it meaningless? Or does it reframe the narrative as a terrifying glimpse into the potential darkness within the protagonist's mind? It’s a choice that certainly pulls the rug out but leaves a lingering sense of ambiguity and, for some, dissatisfaction.

***

Boxing Helena is a cinematic curiosity, a film whose troubled production and controversial premise arguably overshadow its actual content. It’s atmospheric, unsettling, and features a committed performance from Julian Sands, but it often feels emotionally distant and narratively thin despite its shocking core. Its ambition is undeniable, but the execution doesn't fully realize the potential of its dark fairy tale. It remains a fascinating, if flawed, artifact of 90s boundary-pushing – more compelling as a conversation piece than as a fully satisfying film.

Rating: 4/10

Final Thought: A film forever boxed in by its own controversy, Boxing Helena is a stark reminder from the VHS shelves that sometimes the most disturbing horrors are not those depicted on screen, but those imagined in the troubled minds behind – and in front of – the camera.