It wasn't just the thumping bassline you remembered; it was the shimmer, the promise of something illicit and impossibly glamorous filtering through the slightly fuzzy tracking lines of a well-worn VHS tape. Watching 54 back in 1998 often felt like pressing your face against the glass of a legendary party, invited to look but maybe not fully feel the pulse within. There was a curious disconnect, a sense that the real story lingered just outside the frame, obscured by velvet ropes and studio notes.

Beyond the Velvet Rope

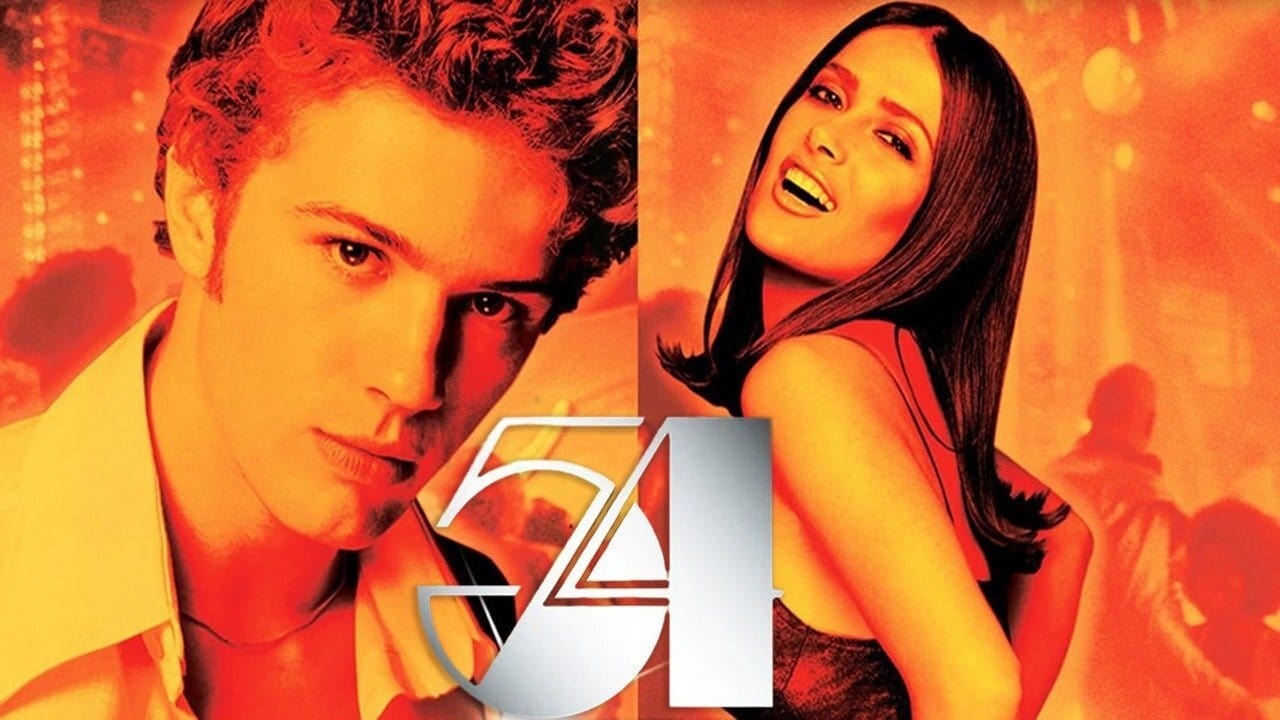

The premise itself holds undeniable allure: Shane O'Shea (Ryan Phillippe), a handsome, naive kid from the wrong side of the tracks in New Jersey, crosses the bridge and finds himself swept into the dizzying orbit of Studio 54, the epicenter of late-70s hedonism. He catches the eye of the club's mercurial co-founder, Steve Rubell (Mike Myers), and is quickly absorbed into the intoxicating world of disco, drugs, and debauchery, becoming a bartender – one of the chosen few serving nectar to the gods of nightlife. Alongside him are fellow aspirants: the ambitious coat-check girl/wannabe singer Anita (Salma Hayek) and her busboy husband Greg (Breckin Meyer). Shane also forms a connection with Julie Black (Neve Campbell), a soap opera starlet navigating the treacherous waters of fame.

A Different Kind of Performance

What immediately struck many viewers back then, and perhaps resonates even more now, was the casting of Mike Myers. Fresh off the phenomenal success of Austin Powers (1997) and known primarily for his brilliant comedic characters on Saturday Night Live, seeing him embody the complex, often predatory Steve Rubell was a genuine shock. Myers sheds his comedic persona entirely, offering a performance that’s surprisingly nuanced and unsettling. He captures Rubell’s desperate need for validation, his sharp business acumen warped by excess, and the darkness lurking beneath the party-host facade. It wasn't the performance many expected, and perhaps its dramatic weight felt slightly out of sync with the film's perceived trajectory at the time, but looking back, it's a genuinely brave and largely successful turn.

Phillippe, embodying the wide-eyed discovery and eventual disillusionment, carries the audience surrogate role well, capturing that deer-in-headlights transition from hopeful outsider to jaded insider. Salma Hayek, radiant and driven as Anita, injects ambition and a yearning for artistic recognition into the proceedings, while Neve Campbell, then at the height of her Scream (1996) fame, brings a touch of fragile celebrity as Julie. Their intertwined stories, however, often felt like they were orbiting a central narrative that wasn't quite allowed to fully form.

The Ghost in the Machine: Studio Interference

And here lies the rub, the reason 54 often felt like a tantalizing glimpse rather than a full immersion. This film carries one of the more infamous tales of studio meddling from the late 90s. Director Mark Christopher envisioned a darker, more complex story exploring the bisexuality of Shane's character and the grittier realities beneath the club's glittery surface. Test audiences reportedly reacted poorly to these elements, particularly the male-male kiss and the overall downbeat tone.

Enter Miramax, notorious for its heavy-handed editing practices. Substantial reshoots were ordered, excising Shane's bisexuality entirely, manufacturing a romance between Shane and Julie (Campbell's character), and generally sanding down the rough edges. This resulted in the theatrical cut most of us rented from Blockbuster – a version that, while visually capturing some of the era's energy, felt narratively compromised and emotionally hollowed out. Reports suggest nearly 45 minutes of original footage were cut, and about 30 minutes of new, studio-mandated material was added. This surgery fundamentally altered the film's DNA, turning a potentially challenging character study into a more conventional rise-and-fall narrative that pulled its punches. The original $13 million budget struggled to recoup, barely making $17 million worldwide – a disappointment given the star power and iconic subject matter.

A Flawed Time Capsule

Despite the behind-the-scenes turmoil, the theatrical cut of 54 wasn't without its merits, especially viewed through that nostalgic VHS lens. It looked the part. The costume design, the pulsating disco soundtrack (Donna Summer, Chic, Sylvester – pure auditory bliss!), the recreation of the club's atmosphere – it all contributed to a certain visual appeal. There was a undeniable thrill in seeing this legendary space brought back to life, even if the drama playing out within felt strangely muted. You could sense the potential, the stronger film lurking beneath the surface, and that perhaps added to its odd fascination. I remember renting this tape, drawn by the cast and the promise of disco decadence, and feeling... well, something was missing, even if I couldn't articulate what back then.

It's worth noting, for context, that Mark Christopher eventually got to release his Director's Cut in 2015. This restored version reinstated the original plot threads, including Shane's relationships with both Anita and Greg, presenting a far richer, darker, and more coherent film that finally fulfilled the initial promise. Seeing it retroactively highlights just how much the 1998 theatrical version was compromised.

Rating & Final Reflection

For the 1998 theatrical version – the one that lived on our shelves and flickered across our CRT screens:

5/10

The rating reflects the film we actually got on VHS back in the day. It’s a fascinating artifact, visually engaging with flashes of brilliance (especially from Myers and the production design), but ultimately a compromised vision. The narrative feels disjointed, the emotional core weakened by studio interference that prioritized perceived palatability over artistic integrity. Yet, there’s an undeniable pull to it, perhaps because of its flaws and the legendary story behind its creation. It captured a specific moment – a 90s attempt to grapple with 70s excess – filtered through a studio system that often feared complexity. What lingers most isn't just the disco beat, but the question of what might have been, a tantalizing echo from a party that ended too soon, or perhaps, was never truly allowed to begin.