Sometimes, amidst the rows of familiar action heroes and neon-drenched comedies lining the video store shelves back in the day, you’d stumble upon something… different. A cover that didn’t scream explosions or slapstick, but hinted at something quieter, perhaps more unsettling. Zeki Demirkubuz’s 1997 film Innocence (Masumiyet) was likely one such tape for many who encountered it – a stark, unforgettable slice of Turkish cinema that lingers long after the VCR whirs to a stop. This isn't a feel-good trip down memory lane; it's a deep dive into the shadowed corners of human connection, obsession, and the quiet desperation that can define a life.

A Corridor of Quiet Despair

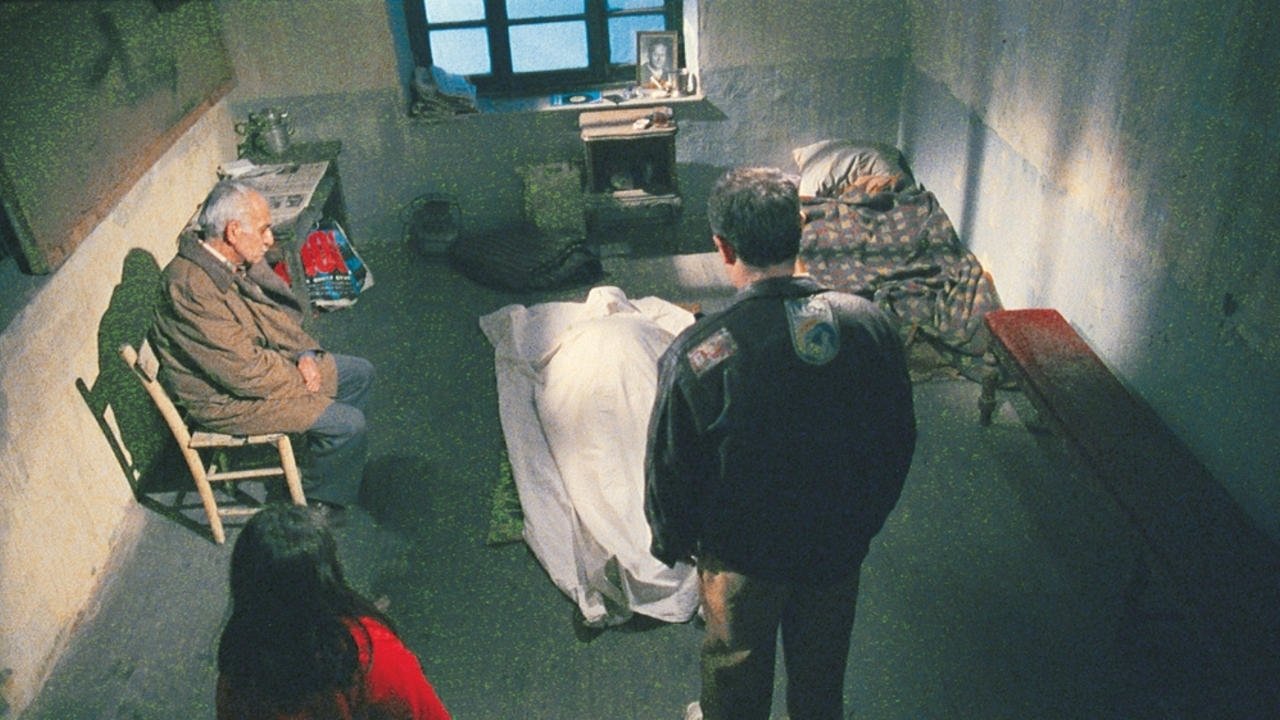

The film introduces us to Yusuf (Güven Kıraç), newly released after a decade in prison for a crime of passion involving his sister's honour. Adrift and seemingly numb, he checks into a cheap, transient hotel. It's here, in these faded, anonymous rooms and dimly lit corridors, that the film truly resides. Yusuf's path crosses with Bekir (Haluk Bilginer) and Uğur (Derya Alabora), a couple locked in a destructive, co-dependent orbit. Bekir is relentlessly devoted to Uğur, a nightclub singer haunted by her own past traumas and losses, including a deaf-mute daughter, Çilem (played with heartbreaking silence by Melis Tuna), who trails them like a small, silent accusation. Yusuf becomes an observer, then an unwilling participant, drawn into their bleak world. Demirkubuz, who also wrote the screenplay, crafts a narrative less concerned with plot mechanics and more with the crushing weight of existence for these characters.

Echoes in Bleak Rooms

What strikes you immediately about Innocence is its atmosphere. Forget the glossy sheen of many late-90s productions; this is gritty, lived-in realism. Demirkubuz uses long takes, often static, forcing us to sit with the characters in their uncomfortable silences and moments of painful honesty. The hotel isn't just a setting; it's a metaphor for purgatory, a waystation for souls who can't move on. The drab wallpaper, the flickering fluorescent lights, the constant hum of unseen lives nearby – it all contributes to a profound sense of isolation, even amidst proximity. There's a palpable sense of lives lived on the margins, wrestling with regret and an inescapable past. Demirkubuz, often compared to Dostoevsky for his exploration of profound human suffering and moral ambiguity, presents a world stripped of easy answers or redemption arcs. It’s said Demirkubuz prefers minimal direction for his actors, allowing their instincts to guide the portrayal of these complex emotional states, a technique that clearly pays dividends here.

Performances Forged in Truth

The film rests heavily on its central trio, and the performances are nothing short of devastating. Haluk Bilginer, who international audiences might recognize from later roles like Winter Sleep (2014) or even Halloween (2018), is a force of nature as Bekir. His obsession with Uğur isn't romanticized; it's portrayed as a consuming, almost pathetic need, yet Bilginer imbues him with a desperate dignity that prevents him from becoming a mere caricature. His extended monologue, delivered with raw, unvarnished pain, is a masterclass in conveying a lifetime of yearning and self-destruction.

Derya Alabora as Uğur is equally compelling. She carries the weight of unspoken trauma in every glance, every weary gesture. Uğur is a woman trapped by circumstance and her own damaged psyche, pushing away connection even as she seems to crave it. Her moments of vulnerability, particularly with her daughter, are piercing. And Güven Kıraç, as the quiet observer Yusuf, provides the audience's entry point. His initial passivity gradually gives way to a reluctant empathy, his minimalist performance perfectly capturing a man slowly re-engaging with the world's pain after years of confinement. You feel his discomfort, his confusion, and ultimately, his quiet resignation.

A Turkish Cinema Landmark

Innocence is often cited as a key work in modern Turkish cinema, part of Demirkubuz's informal "Tales of Darkness" trilogy alongside C Blok (1994) and The Third Page (1999). Made on a modest budget, its power comes not from spectacle but from its unflinching gaze into the human soul. There's a story, perhaps apocryphal but fitting, that Demirkubuz, known for his exacting vision, meticulously planned shots to maximize the emotional impact within his financial constraints, proving that powerful cinema doesn't always require blockbuster resources. The film garnered significant acclaim in Turkey and at international film festivals, signaling Demirkubuz as a major directorial voice. Its themes of fate, inescapable pasts, and the complexities of love and dependency resonate universally, even if the specific cultural context feels distinct. Watching it now, years after its initial release, it feels less like a product of the 90s and more like a timeless exploration of human frailty.

Final Thoughts

Innocence isn't an easy watch. It doesn't offer catharsis or neat resolutions. It leaves you contemplating the characters' intertwined fates, the cycles of pain they seem unable to break. Was Yusuf's release from prison merely an exchange for a different kind of confinement? Can people truly escape the gravity of their past actions and relationships? The film offers no simple answers, only quiet, profound observations. It’s the kind of movie that might have been overlooked in the video store, mistaken for something slow or depressing, but for those who took a chance, it offered a potent dose of cinematic truth.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's masterful direction, powerhouse performances, and unflinching thematic depth. It's a challenging but immensely rewarding piece of cinema, achieving profound emotional resonance through its stark realism and compassionate portrayal of deeply flawed characters. Its bleakness prevents a perfect score, as it's undeniably demanding viewing, but its artistic merit is undeniable.

Innocence is a testament to the enduring power of character-driven drama, a reminder that sometimes the most impactful stories are found not in grand narratives, but in the quiet desperation echoing down a lonely hotel corridor. It stays with you, a haunting whisper from the VHS era.