Out there, under the unforgiving Texas sun, a bleached skull and a sheriff's badge are unearthed from the dust. It's more than just bone and rusted metal; it's the cracking open of a past deliberately buried, a history the small border town of Frontera has tried hard to forget. Watching John Sayles' Lone Star (1996) again recently, perhaps on a well-loved tape fetched from the back shelf, that opening image resonates just as powerfully. It’s the catalyst for a story that unfolds not with frantic action, but with the slow, deliberate pace of secrets rising to the surface, like silt disturbed in a long-stagnant river. This isn't just a mystery; it's an excavation of the human heart and the tangled roots of community.

Where the Past Isn't Even Past

What Sayles, a true auteur who often funded his thoughtful character studies by writing or rewriting more mainstream fare (rumor has it his uncredited work on Apollo 13 helped finance this), does so brilliantly here is weave multiple narratives across time. The central investigation by Sheriff Sam Deeds (Chris Cooper) into the decades-old disappearance of the corrupt, legendary Sheriff Charley Wade (Kris Kristofferson) becomes a lens through which we examine the town's entire history. The racial tensions between the Anglo, Black, and Chicano communities aren't just backdrop; they are the very fault lines along which the story tremors. Sam, living in the shadow of his revered father, Buddy Deeds (Matthew McConaughey in flashbacks), embodies this tension. He’s a man trying to step out from under a legend, only to find the past clinging to him like the pervasive desert heat. Sayles never simplifies these complex dynamics; he lets them breathe, allowing the audience to piece together the fractured history alongside Sam.

Faces in the Frontera Sun

The performances in Lone Star feel less like acting and more like inhabiting. Chris Cooper, before he became a more widely recognized Oscar-winner, delivers a masterclass in quiet integrity and burdened introspection. His Sam Deeds carries the weariness of a man wrestling with ghosts – both literal and figurative. You see the weight in his posture, hear the doubt in his measured drawl. Opposite him, the late, wonderful Elizabeth Peña as Pilar Cruz, Sam's former flame and a local teacher grappling with her own family history and cultural identity, is simply luminous. Their scenes together crackle with the unresolved longing and shared history that defines so much of the film.

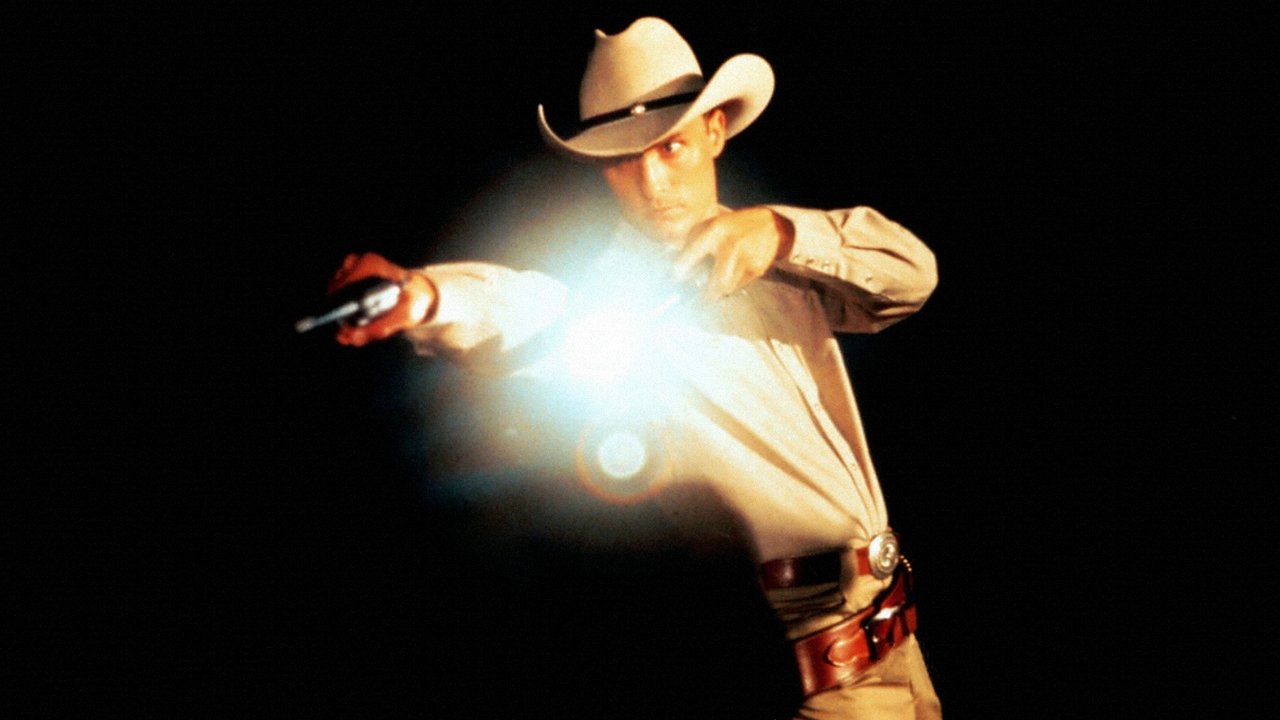

And then there's Matthew McConaughey, captured right at that moment his star was ascending (A Time to Kill hit screens the same year). His Buddy Deeds isn't just a flashback placeholder; he’s a figure of magnetic charisma, radiating the effortless authority and potential menace that legends are built on. It’s a perfectly calibrated performance that makes you understand why his shadow looms so large over Frontera. The entire ensemble, including memorable turns from Joe Morton as the estranged son of a local Black community leader and Frances McDormand in a smaller but impactful role, contributes to the film's rich, lived-in feel. It feels like a real town, populated by real people carrying real baggage.

A Story Told with Patience and Place

Sayles directs with a confident, unhurried hand. He trusts his audience, layering flashbacks seamlessly into the present-day narrative without resorting to stylistic gimmicks. You're never confused about when you are, only drawn deeper into how the then informs the now. The film, shot beautifully on location in and around Del Rio, Texas (standing in for the fictional Frontera), captures the specific atmosphere of a border town – the cultural crossroads, the simmering tensions, the sense of being caught between worlds. It was made for a relatively modest sum, reportedly around $3.5 million, yet feels expansive in its scope and thematic depth, a testament to Sayles' resourceful, character-driven approach to filmmaking – a hallmark of independent cinema thriving in the mid-90s. He wasn't just telling a story; he was mapping the soul of a place.

The Truth, Buried and Unearthed

(Minor Spoilers Ahead!) As Sam's investigation progresses, the truth about Charley Wade's fate becomes intertwined with deeply personal revelations. The film elegantly reveals that the skeletons people hide aren't always literal. The affair between Sam and Pilar, forbidden years ago by their parents, takes on new, complicated dimensions as family secrets unravel. What Lone Star ultimately suggests is that history, personal and communal, is a story we construct. The question isn't just what happened, but why we choose to remember it certain ways. Doesn't that resonate with how families and communities grapple with their own legacies today? The way Sayles handles the final, challenging revelation is both shocking and profoundly human, leaving judgment aside in favor of understanding the impossible choices people make.

Legacy in the Dust

Lone Star remains a potent piece of American filmmaking, a complex, multi-layered narrative that rewards patient viewing. It tackles big themes – race, history, identity, reconciliation – with nuance and empathy, grounded in unforgettable characters. It's the kind of thoughtful, adult drama that felt like a vital part of the cinematic landscape back when video stores offered aisles of discovery beyond the blockbusters. I distinctly remember renting this one, drawn perhaps by McConaughey's rising fame, but finding something far richer and more lasting.

Rating: 9/10

This near-masterpiece earns its score through John Sayles' intricate, intelligent script (which rightfully earned an Oscar nomination), the superb, authentic performances across the board (especially from Cooper and Peña), and its powerful, unflinching exploration of how the past forever shapes the present. It’s a slow burn, yes, but the heat it generates lingers long after the credits roll.

What Lone Star leaves us with isn't easy answers, but a profound sense of the tangled, often painful, always interconnected nature of human lives – a truth as vast and complex as the Texas sky under which its story unfolds.