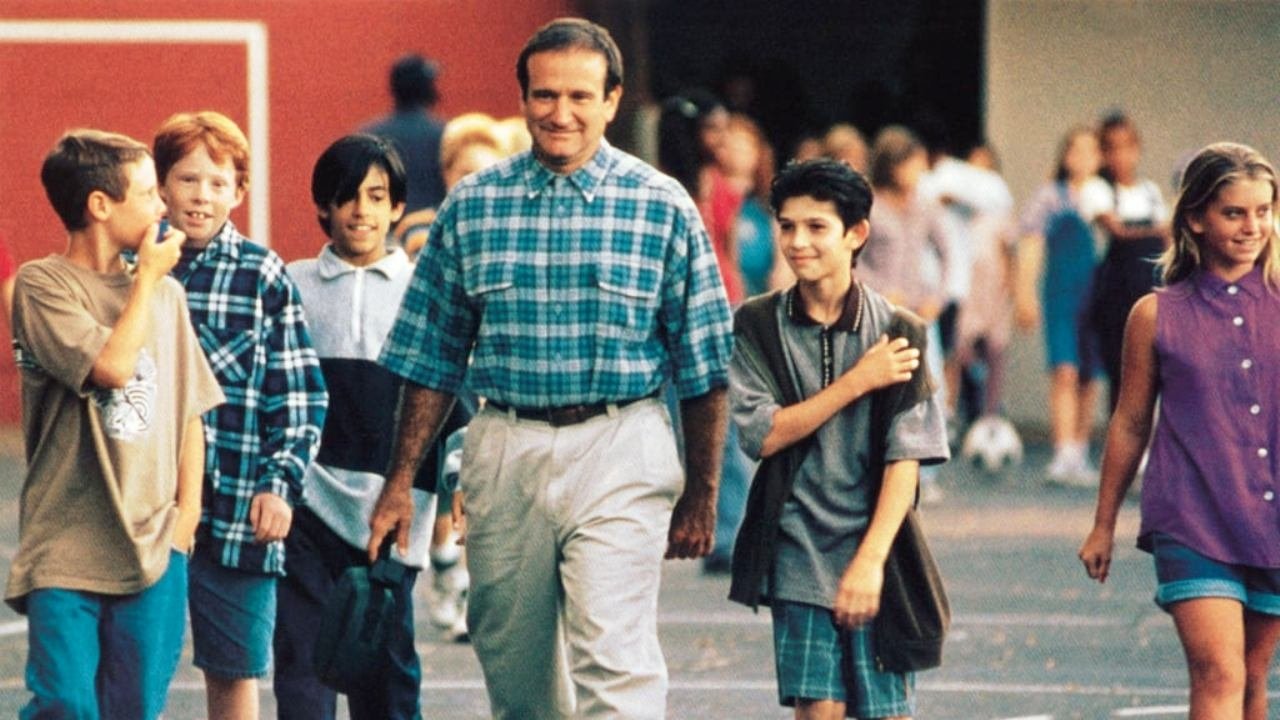

It's a curious thing, isn't it? Seeing the name Francis Ford Coppola – the titan behind The Godfather (1972), The Conversation (1974), Apocalypse Now (1979) – attached to a film like Jack. Released in 1996, this wasn't the gritty crime drama or intense war epic associated with the legendary director. Instead, video store shelves presented us with a brightly coloured cover featuring Robin Williams, sporting an impish grin but looking distinctly middle-aged, surrounded by kids. The premise itself felt like pure 90s high-concept: a boy born with a rare condition causing him to age four times faster than normal. A ten-year-old in the body of a forty-year-old. It’s a setup ripe for broad comedy, but revisiting Jack now, what lingers isn't just the expected fish-out-of-water humour, but a surprising, sometimes awkward, vein of melancholy running right through its core.

A Race Against Time

The film throws us straight into the whirlwind life of Jack Powell. His parents, Karen (Diane Lane) and Brian (Brian Kerwin), navigate the shock and challenges of his condition with a blend of love and trepidation. Kept initially isolated due to fears about his physical fragility and social acceptance, Jack yearns for the normalcy of childhood – friendships, schoolyard games, simply fitting in. When a compassionate tutor, Mr. Woodruff (Bill Cosby, in a role viewed very differently today), advocates for Jack to attend public school, the film sets up its central conflict: can this rapidly aging boy experience the joys of youth before time runs out?

It's a narrative tightrope walk. The screenplay, penned by James DeMonaco (who would later give us the vastly different The Purge series) and Gary Nadeau, attempts to balance slapstick moments – Jack trying to navigate school desks, experiencing puberty almost overnight, the inherent comedy of a 'grown man' acting like a child – with poignant observations about mortality and the fleeting nature of innocence. Does it always succeed? Perhaps not seamlessly. There are moments where the tonal shifts feel abrupt, where a gag sequence bumps uncomfortably against a moment of genuine emotional weight. I recall renting this on VHS, perhaps expecting something more akin to Big (1988), and being caught slightly off-guard by the film's more somber undercurrents.

The Heart of the Matter: Williams and Lane

What truly anchors Jack, preventing it from dissolving into either pure schmaltz or awkward comedy, is the central performance by Robin Williams. In 1996, Williams was at the height of his powers, capable of dazzling comedic improvisation (Mrs. Doubtfire (1993)) and deeply felt dramatic work (Dead Poets Society (1989), Good Will Hunting (1997) would follow soon after). Here, he had to embody the boundless energy, curiosity, and vulnerability of a ten-year-old boy trapped in an aging body. It’s a task demanding immense physical control and emotional transparency. Williams largely pulls it off, capturing the wide-eyed wonder and the heartbreaking confusion of Jack’s situation. Yes, there are flashes of familiar Williams-esque mania, but beneath it, there's a palpable sense of Jack's loneliness and his desperate desire to connect. We believe his joy in simple childhood pleasures and feel the sting of his awareness that his time is tragically limited.

Equally crucial is Diane Lane as Karen. Her performance is the film’s emotional bedrock. She conveys the fierce protectiveness, the quiet heartbreak, and the unwavering love of a mother watching her child live an entire life in fast-forward. Her chemistry with Williams feels genuine; their scenes together ground the fantastical premise in recognizable human emotion. There’s a quiet power in her portrayal that prevents the film from becoming solely about Jack's condition, reminding us of the profound impact it has on those who love him.

Coppola's Touch and Retro Reflections

Why did Coppola, known for his intense, auteur-driven projects, take on Jack? Accounts suggest he connected with the theme of lost childhood, perhaps seeking a different kind of filmmaking experience after some financially challenging periods with his Zoetrope Studios. While Jack doesn't bear the stylistic hallmarks of his most famous works, there's a warmth and visual clarity to it. He allows the performances, particularly Williams', room to breathe. The film reportedly cost around $45 million and pulled in a respectable but not blockbuster $120 million worldwide, suggesting audiences connected with its emotional core despite mixed critical reactions at the time (many critics pointed out the tonal inconsistencies).

Watching it now, certain aspects feel undeniably of their time – the fashion, the school environment, the specific brand of earnestness. Some of the humour, especially surrounding Jack's interactions with his young friends (played capably by actors like Adam Zolotin and a young Jennifer Lopez in an early role as his teacher Miss Marquez), lands differently through a modern lens. Yet, the core themes remain potent. The film asks us to consider the value of each moment, the importance of connection, and the bittersweet reality that life, no matter how long, is finite. Doesn’t Jack’s accelerated journey simply highlight the preciousness we often overlook in our own lives?

Final Thoughts: A Bittersweet Time Capsule

Jack is not a perfect film. Its blend of comedy and drama can be uneven, and some moments might feel overly sentimental. However, it possesses a genuine heart, largely thanks to the committed performances of Robin Williams and Diane Lane. It tackles surprisingly deep themes for what might appear, on the surface, to be a simple family comedy. There's an undeniable poignancy, particularly watching Williams embody such youthful exuberance while grappling with the physical realities of aging – a poignancy amplified by our knowledge of his own tragically shortened life. It remains a fascinating, slightly odd entry in both Williams' and Coppola's filmographies, a 90s curio that aimed for laughter but resonates more deeply in its exploration of life's fleeting beauty.

Rating: 6/10

The score reflects the film's undeniable heart and strong central performances, particularly from Williams and Lane, which elevate the material. However, it's docked points for its sometimes jarring tonal shifts and moments where the blend of comedy and pathos doesn't quite gel, preventing it from reaching the heights of truly great family dramas or comedies.

It’s a film that stays with you, perhaps not for its comedic set pieces, but for that underlying ache of time passing too quickly – a feeling many of us understand all too well, looking back from the other side of the VCR era.