There’s a particular kind of raw nerve ending exposed in Gregg Araki’s 1994 film, Totally F*ed Up, a feeling that digs under your skin long after the static hiss of the VHS tape fades. This wasn't a movie you stumbled upon easily in the brightly lit aisles of Blockbuster; finding it often meant venturing into the indie or LGBTQ+ section of a more discerning video store, pulling out a tape whose very title felt like a dare. Watching it then, often on a fuzzy CRT screen, felt like intercepting a broadcast from a world both aggressively stylized and painfully real. It wasn't comfortable, but it felt necessary, didn't it?

Fifteen Fragments of Fury and Malaise

Billed by Araki himself as "a kinda homosexual Breakfast Club," Totally F*ed Up throws us into the lives of six queer teenagers adrift in Los Angeles. Forget neat character arcs or a tidy plot; the film presents itself as "15 random celluloid fragments," a structure mirroring the disjointed, media-saturated reality its characters inhabit. We follow Andy (James Duval, in his first collaboration with Araki, marking the start of a significant indie partnership), Tommy (Roko Belic, who later found success directing documentaries like Genghis Blues), Michele (Susan Behshid), Patricia (Jivin Lazarus), Steven (Gilbert Luna), and Deric (Lance May). They hang out, they hook up, they talk – endlessly, sometimes profound, often profane – about sex, love, movies, alienation, and the suffocating straight world around them. The narrative, such as it is, floats between moments of tender connection, biting humor, aimless boredom, and sudden bursts of violence or despair.

The Raw Truth of Lo-Fi Rebellion

What immediately strikes you, revisiting Totally F*ed Up today, is its defiantly unpolished aesthetic. Araki, operating on a shoestring budget often cited as being incredibly low (some reports say as little as $5,000, though perhaps closer to $20,000 is more realistic – peanuts even then!), embraced the limitations. Much of the film was shot on Hi8 video, interspersed with grainy 16mm film, giving it a texture that feels deliberately confrontational. This wasn’t Hollywood gloss; this was guerrilla filmmaking fueled by punk rock energy and righteous anger. The very look of the film – its sometimes murky visuals, its abrupt cuts – becomes part of its message. It rejects slick consumerism, mirroring the characters' own rejection of mainstream assimilation. Does that visual roughness sometimes test patience? Perhaps. But it also lends an undeniable authenticity, a feeling that we're watching something captured, not constructed. It’s a potent reminder of how accessible formats like VHS and Hi8 empowered a generation of indie filmmakers to tell stories outside the system.

The performances carry this same raw energy. These aren't typically polished portrayals; they feel jagged, immediate, and deeply felt. James Duval, as the sensitive aspiring filmmaker Andy whose video camera often serves as our window into their world, embodies a particular kind of quiet desperation. The ensemble captures the specific rhythms of teenage friendship – the in-jokes, the sudden resentments, the fierce loyalty. Their dialogue, penned by Araki, crackles with a cynical wit that often masks deep vulnerability. It’s a snapshot of a specific moment – post-Reagan, pre-internet ubiquity, living under the shadow of the AIDS epidemic – and the anxieties feel terrifyingly relevant.

More Than Just Teen Angst

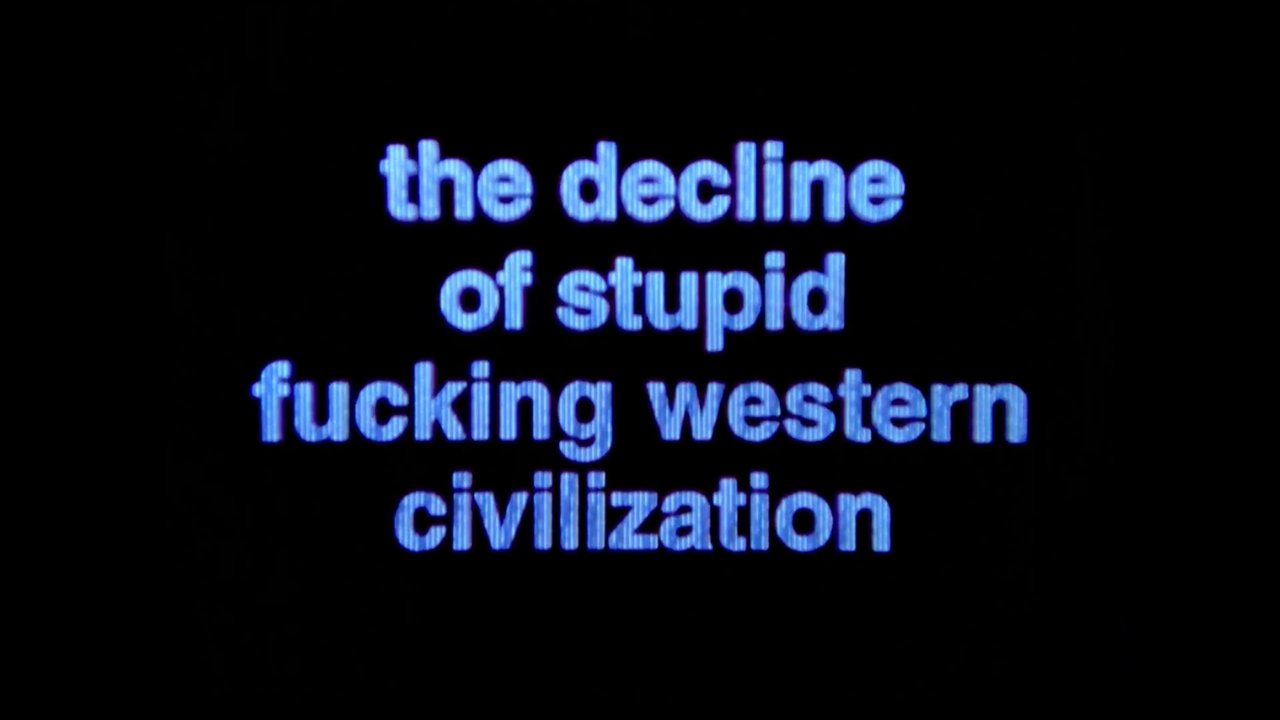

Beneath the explicit content and the sometimes-abrasive style, Totally F*ed Up grapples with profound themes. It’s a stark portrayal of queer alienation, the search for chosen family when biological family and society offer rejection or indifference. The film doesn't shy away from the harsh realities faced by LGBTQ+ youth, including homophobia, violence, and the devastating impact of HIV/AIDS, which hangs like an unspoken dread over many scenes. The characters' cynicism isn't just affectation; it's a shield against a world that seems actively hostile.

This film marked the beginning of Araki's informal "Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy," followed by the more narratively conventional (but no less provocative) The Doom Generation (1995) and Nowhere (1997). Watching Totally F*ed Up provides crucial context for those later works, establishing the director's thematic preoccupations and his distinctive visual language. Its influence on subsequent queer cinema and defiant indie filmmaking is undeniable, paving the way for other uncompromising voices. It reminds us that anger can be an engine for art, and that sometimes the most vital stories are the ones told from the margins, with whatever tools are available.

Still Fed Up, Still Necessary*

Revisiting Totally F*ed Up isn't necessarily a comfortable experience. Its bleakness is pervasive, its ending is shattering, and its lo-fi aesthetic can be challenging. Yet, its power remains undimmed. It captures a specific generational malaise and queer experience with unflinching honesty and surprising moments of tenderness amidst the rage. It’s a film that feels ripped directly from the veins of its creator and its time. For those of us who encountered it on a worn VHS tape back in the day, it felt like a transmission from an urgent, unseen reality.

Rating: 8/10

Justification: This score reflects the film's raw power, its historical significance within independent and queer cinema, and its courageous, uncompromising vision. Gregg Araki's ability to create such a potent statement on a micro-budget is remarkable. The performances possess a vital authenticity, and the film's thematic concerns remain sadly relevant. It loses points perhaps for an aesthetic that, while intentional, can sometimes feel alienating or crude, and a narrative structure that intentionally resists conventional satisfaction. It's not an easy watch, but its importance and impact are undeniable.

Final Thought: Totally F*ed Up remains a vital, ragged scream of a film – a Molotov cocktail thrown at complacency, still radiating heat and urgency decades later. It’s a testament to the enduring power of telling necessary stories, no matter the budget.