## The Echo in the Dark

What happens when the storm outside is nothing compared to the tempest raging within? Roman Polanski’s Death and the Maiden (1994) throws us headfirst into such a scenario, locking us in a remote beach house with three characters and a past that refuses to stay buried. It’s a film that arrived on VHS shelves perhaps looking like a standard thriller, but unwound into something far more unsettling – a tense, claustrophobic chamber piece wrestling with trauma, justice, and the terrifying unreliability of memory. I remember renting this one, drawn perhaps by the familiar faces of Sigourney Weaver and Ben Kingsley, and finding myself pinned to the sofa by its sheer intensity, the flickering CRT glow amplifying the shadows both literal and psychological.

A Knock at the Door, A Voice from the Past

The setup is deceptively simple. Paulina Escobar (Sigourney Weaver), a former political prisoner still deeply scarred by her torture under a brutal dictatorship, lives in anxious seclusion with her husband Gerardo (Stuart Wilson), a prominent lawyer recently appointed to head a human rights commission investigating the regime's crimes. One dark and stormy night – the kind of pathetic fallacy that feels almost classical here – Gerardo gets a flat tire and is helped by a stranger, Dr. Roberto Miranda (Ben Kingsley). When Miranda later returns Gerardo’s forgotten spare, Paulina overhears his voice, his mannerisms, certain turns of phrase... and is instantly convinced he is the very doctor who presided over her torture and rape years ago, often while playing Schubert's "Death and the Maiden" quartet.

What follows is a harrowing night where Paulina, armed with Gerardo’s gun, takes Miranda captive, determined to extract a confession and mete out her own form of justice. Gerardo, the man of law and due process, finds himself caught between his traumatized wife's terrifying certainty and the potential innocence of their captive guest. The house becomes a pressure cooker, the relentless storm outside echoing the escalating emotional violence within.

Three Souls in Close Quarters

The film lives and dies on its three central performances, and thankfully, they are exceptional. Sigourney Weaver, stepping far away from the sci-fi heroism of Alien (1979) or the dedicated research of Gorillas in the Mist (1988), delivers a raw, frayed nerve of a performance. Her Paulina is volatile, fragile, yet possessed of a chilling conviction. Weaver doesn't shy away from the character's less sympathetic actions; she embodies the consuming nature of trauma, how it can warp perception and drive one to extremes. You see the terror flicker in her eyes, the sudden shifts from victim to aggressor – it’s a physically and emotionally demanding role, navigated with stunning authenticity.

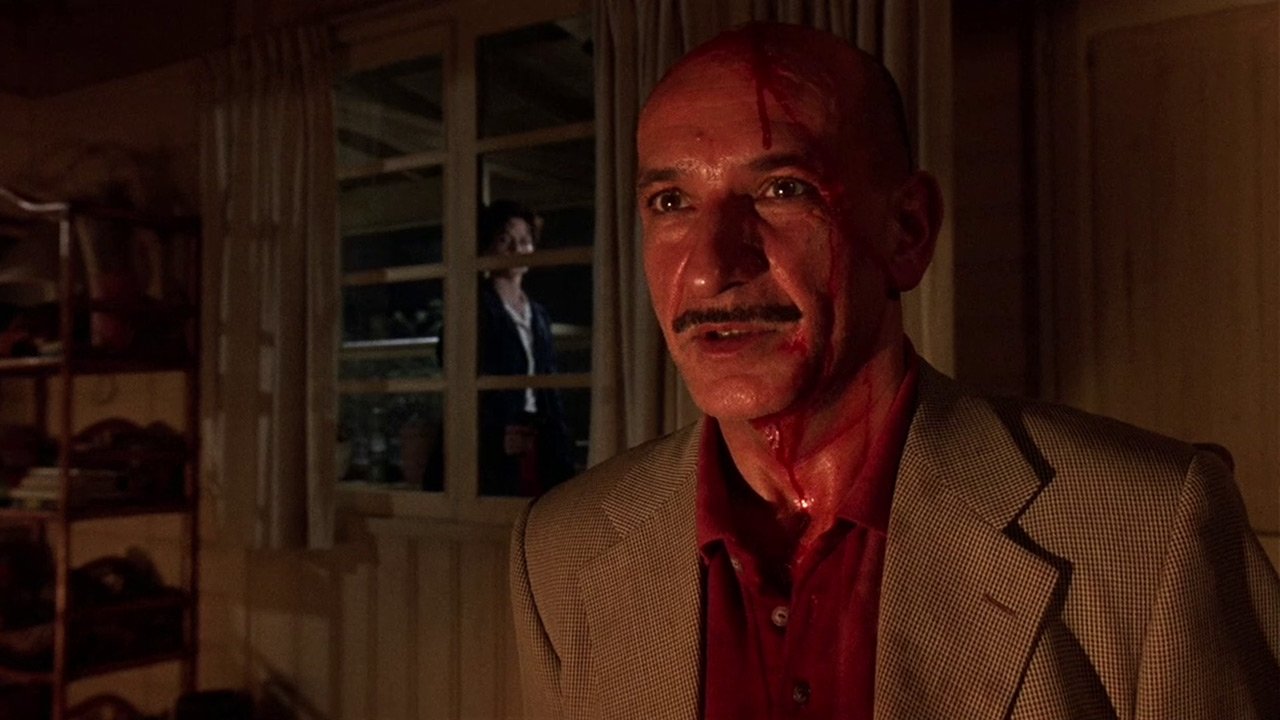

Ben Kingsley, ever the master of nuance (Gandhi (1982) feels a world away here), is perfectly cast as Dr. Miranda. Is he the monster Paulina remembers, or merely an unfortunate man in the wrong place at the wrong time? Kingsley plays this ambiguity brilliantly. His Miranda is outwardly civilized, rational, even charmingly flustered at first, but there are flashes – a turn of phrase, a flicker in his eyes – that keep the viewer guessing. He maintains a careful composure that could be interpreted as innocence under duress, or the practiced mask of a perpetrator. It’s a testament to his skill that, even by the end, certainty remains elusive.

Stuart Wilson has the perhaps thankless role of Gerardo, the man caught in the middle. He represents the liberal ideal of reconciliation and legal process, starkly contrasted with Paulina’s visceral need for retribution. Wilson portrays Gerardo’s anguish effectively – his love for his wife warring with his principles, his dawning horror at what she’s capable of, and his own uncomfortable compromises. He is the audience’s conflicted surrogate, asking the questions we might ask, trapped in an impossible situation.

Polanski's Confined Vision

Director Roman Polanski, no stranger to enclosed spaces and psychological turmoil (Repulsion (1965), Rosemary's Baby (1968), The Tenant (1976)), masterfully uses the single location (primarily shot chronologically on sets in Paris) to heighten the claustrophobia. The camera often feels like a fourth, unseen presence in the room, prowling, observing, trapping the characters in tight frames. The storm rages outside the windows, isolating them further, mirroring the internal chaos. Polanski’s direction is controlled and precise, focusing intently on the shifting power dynamics and the raw emotions erupting within the house. There's a palpable sense of danger, not just from Paulina's gun, but from the eruption of buried pain.

The screenplay, adapted by Ariel Dorfman (author of the original acclaimed play) and Rafael Yglesias, retains the theatrical intensity. It’s dialogue-heavy, but the words are weapons, confessions, accusations, and justifications. Interestingly, Dorfman, himself exiled from Chile during Pinochet's regime, brings a profound understanding of the lingering wounds left by such dictatorships. The film doesn't explicitly name the country, making its themes terrifyingly universal.

The Weight of Uncertainty

Death and the Maiden isn't interested in easy answers. It forces us to confront difficult questions. Can trauma ever truly be overcome? What constitutes justice when the legal system seems inadequate or compromised? Can truth be definitively known when memory itself is a fragile, subjective thing? Paulina's methods are brutal, mirroring the very torture she endured. Does the film endorse her actions? Condemn them? Or simply present them as the tragic consequence of unbearable suffering?

The film's infamous ending, shifting from the contained tension of the house to a public concert hall, offers no simple resolution. The ambiguity lingers long after the credits roll. Did Miranda confess truthfully under duress, or simply say what Paulina needed to hear? Does Paulina achieve peace, or is she forever haunted? It’s this refusal to neatly tie things up that gives the film its lasting power. It leaves the viewer grappling with the moral complexities, much like the characters themselves. Despite a modest budget (around $12 million) and a quiet run at the box office (just over $3 million in the US), its thematic weight ensures it remains a significant, if challenging, piece of 90s cinema.

Rating: 8/10

Death and the Maiden is a demanding but rewarding watch. It’s a film powered by three phenomenal performances, particularly Weaver's shattering portrayal of trauma, and guided by Polanski’s taut, claustrophobic direction. It may lack the overt thrills some might expect from the cast or director, focusing instead on psychological intensity and complex moral questions. The 8 rating reflects its superb acting, atmospheric tension, and brave exploration of difficult themes, acknowledging that its deliberate ambiguity and stagey origins might not resonate with everyone seeking straightforward closure. It's a film that gets under your skin, a potent reminder from the VHS era that some storms never truly pass.

What price justice, and who gets to decide when it's been served? Death and the Maiden leaves you pondering that, long after the tape has been ejected.