That pristine white beach house, perched against the blue canvas of the Atlantic, seemed like the very definition of the American dream in 1991. Yet, within those immaculate walls, behind the perfectly aligned towels and the gleaming surfaces, director Joseph Ruben spun a tale that was anything but dreamy. Sleeping with the Enemy arrived on VHS shelves riding a wave of Julia Roberts mania, fresh off her career-defining turn in Pretty Woman (1990). But the charm audiences expected was quickly overshadowed by a chilling, palpable dread, reminding us that perfection is often the most terrifying mask of all.

### The Gilded Cage

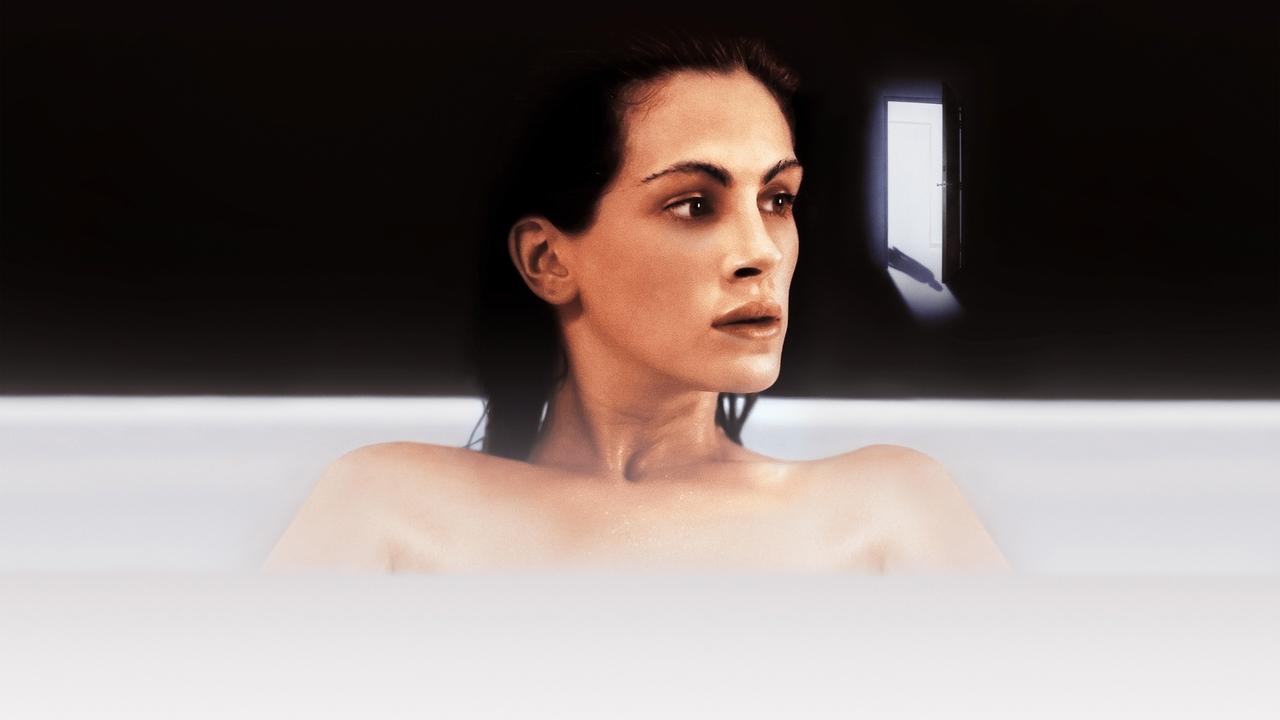

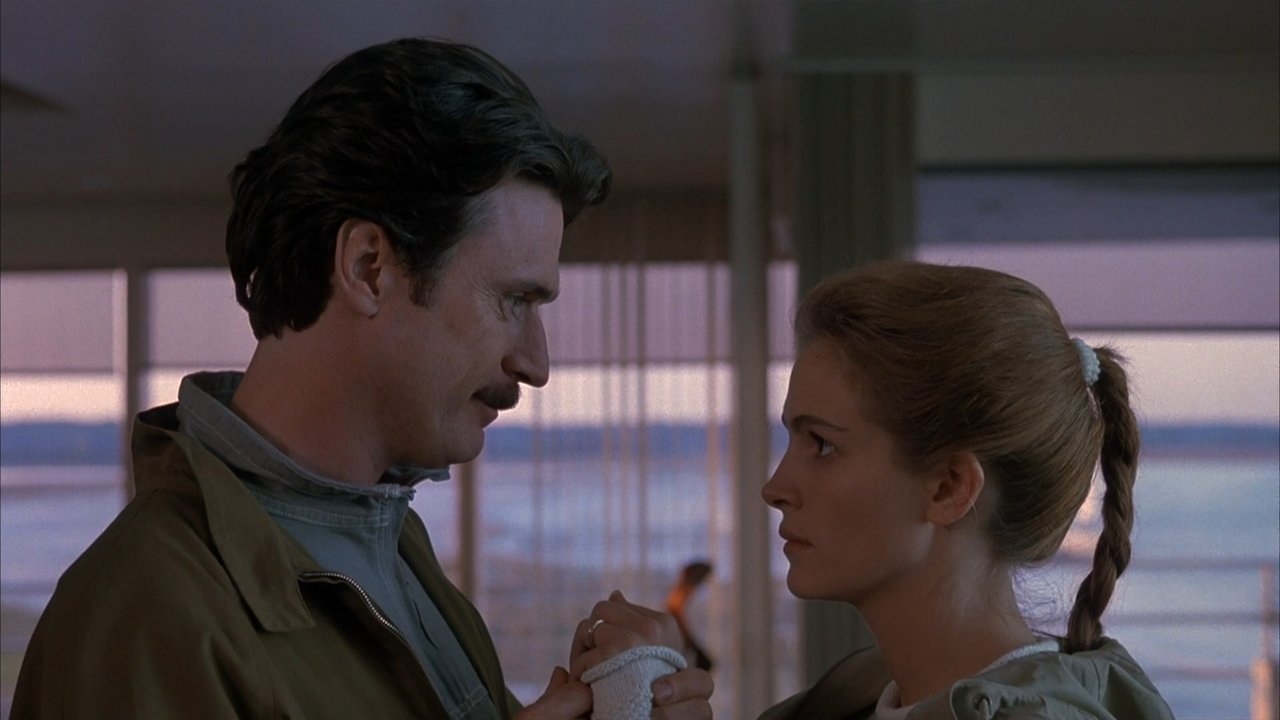

The setup is deceptively simple, yet instantly unnerving. Laura Burney (Julia Roberts) lives an outwardly idyllic life with her handsome, successful husband, Martin (Patrick Bergin). Their oceanfront home is a marvel of order and taste. But it’s his order, his taste. Every misplaced hand towel, every can not facing precisely forward in the cupboard, invites not just correction, but a simmering, controlled rage that feels perpetually moments from boiling over. Patrick Bergin, relatively unknown to American audiences before this role, is remarkably effective. He doesn't play Martin as a scenery-chewing monster, but as something far more insidious: a man whose possessiveness is woven into the very fabric of his being, masked by outward charm and underscored by the obsessive strains of Berlioz's "Symphonie fantastique". His calm demeanor during moments of intense psychological abuse is arguably more frightening than any overt outburst would be. It's a performance that gets under your skin, making the audience complicit in Laura's desperate need to escape.

### A Daring Escape, A Tentative Rebirth

The film hinges on Laura’s meticulously planned escape – faking her death during a sudden storm at sea. It’s a sequence handled with taut efficiency by Ruben, setting the stage for the film's second act. Shedding her identity, Laura becomes Sara Waters and flees to the unassuming, landlocked town of Cedar Falls, Iowa (portrayed convincingly by Abbeville, South Carolina, while the coastal scenes used North Carolina's stunning Wrightsville Beach and Figure Eight Island). Here, the film’s visual palette shifts. The cold, blue-and-white precision of the Cape Cod house gives way to warmer, earthier tones. Sara tentatively builds a new life, finding kindness and a potential connection with her quirky, gentle neighbor, Ben Woodward (Kevin Anderson), a local drama teacher.

It's in these Iowa scenes that Julia Roberts truly anchors the film. Having proven her megawatt charisma, here she navigates the difficult terrain of portraying trauma and resilience. We see the lingering effects of Martin’s control in her jumpiness, her suspicion, her difficulty accepting simple kindness. It’s a performance layered with vulnerability, but also a burgeoning strength as Sara slowly reclaims her identity. Roberts reportedly found the intense scenes depicting Martin's abuse draining to film, and that rawness translates onto the screen, lending authenticity to Sara’s journey. You feel her terror, but also root desperately for her fragile steps towards freedom. Kevin Anderson provides a necessary counterpoint – his Ben is perhaps a touch idealized, the 'nice guy' antidote to Martin's toxicity, but his warmth feels genuine and crucial to Sara's healing process.

### Behind the Glossy Thrills

Penned by Ronald Bass, who had recently won an Oscar for Rain Man (1988), and based on Nancy Price's novel, the script efficiently balances suspense with character development, particularly in the first two acts. While Kim Basinger was reportedly considered for Laura, it's hard to imagine the film having the same cultural impact without Roberts' star power at that specific moment. The movie struck a chord, becoming a massive box office hit – earning a staggering $175 million worldwide against a modest $19 million budget (that's roughly $390 million against $42 million in today's money!), cementing its place as a defining thriller of the early 90s.

Part of its success lies in how it taps into primal fears – the fear of being trapped, of being controlled, of the monster hiding in plain sight. Ruben, who also directed the unsettling The Stepfather (1987), demonstrates a knack for using visual cues to build tension. The obsessive neatness of Martin's house isn't just set dressing; it's a physical manifestation of his controlling psyche. Even after Sara escapes, the lingering threat of Martin's discovery hangs heavy over the seemingly peaceful Iowa scenes. Did anyone else find themselves scanning the background of every frame, expecting Martin to suddenly appear?

The film isn’t without its flaws. The third act, when Martin inevitably tracks Sara down, arguably leans into more conventional thriller tropes, perhaps sacrificing some of the earlier psychological nuance for jump scares and a climactic confrontation. Some critics at the time noted this shift, finding the ending somewhat formulaic compared to the unsettling realism of the setup. Yet, even with these criticisms, the core tension remains effective.

### Lasting Impressions

Sleeping with the Enemy occupies a specific space in the VHS pantheon. It wasn't high art, perhaps, but it was a slick, effective, and immensely popular thriller that brought a difficult subject – domestic abuse – into mainstream conversation, albeit wrapped in Hollywood gloss. It delivered suspense, a chilling villain, and a star-making turn that solidified Julia Roberts as America’s sweetheart, even when playing a woman haunted by terror. I remember renting this one, the iconic cover art promising glamour and intrigue, and being completely gripped by the tension, the fear feeling surprisingly real despite the movie-star sheen. It tapped into anxieties that felt relevant then and, sadly, still resonate today.

Rating: 7/10

The score reflects the film's undeniable effectiveness as a mainstream thriller bolstered by strong central performances, particularly Bergin's chilling portrayal and Roberts' compelling journey. It successfully builds suspense and tackles a serious theme, though it dips into more conventional territory in its final act. Still, a highly memorable entry in the early 90s thriller canon.

What lingers most, perhaps, isn't just the suspense, but that unsettling image of the perfect house – a potent reminder that the most frightening dangers can hide behind the most beautiful facades. Didn't it make us all look twice at seemingly perfect couples for a little while?