It’s a curious thing, looking back. Sometimes the films that linger aren't the ones with the loudest explosions or the biggest box office returns, but the quieter ones, the character studies that nestled onto the video store shelves almost unnoticed. Mel Gibson's directorial debut, The Man Without a Face (1993), felt like such a film. Arriving amidst Gibson's action-hero peak, seeing him step behind the camera for this measured, poignant drama was certainly a shift, a signal of different ambitions simmering beneath the surface. Renting this tape often felt like choosing the thoughtful indie over the summer blockbuster – a choice that, for many of us, yielded unexpected rewards.

An Unlikely Classroom by the Sea

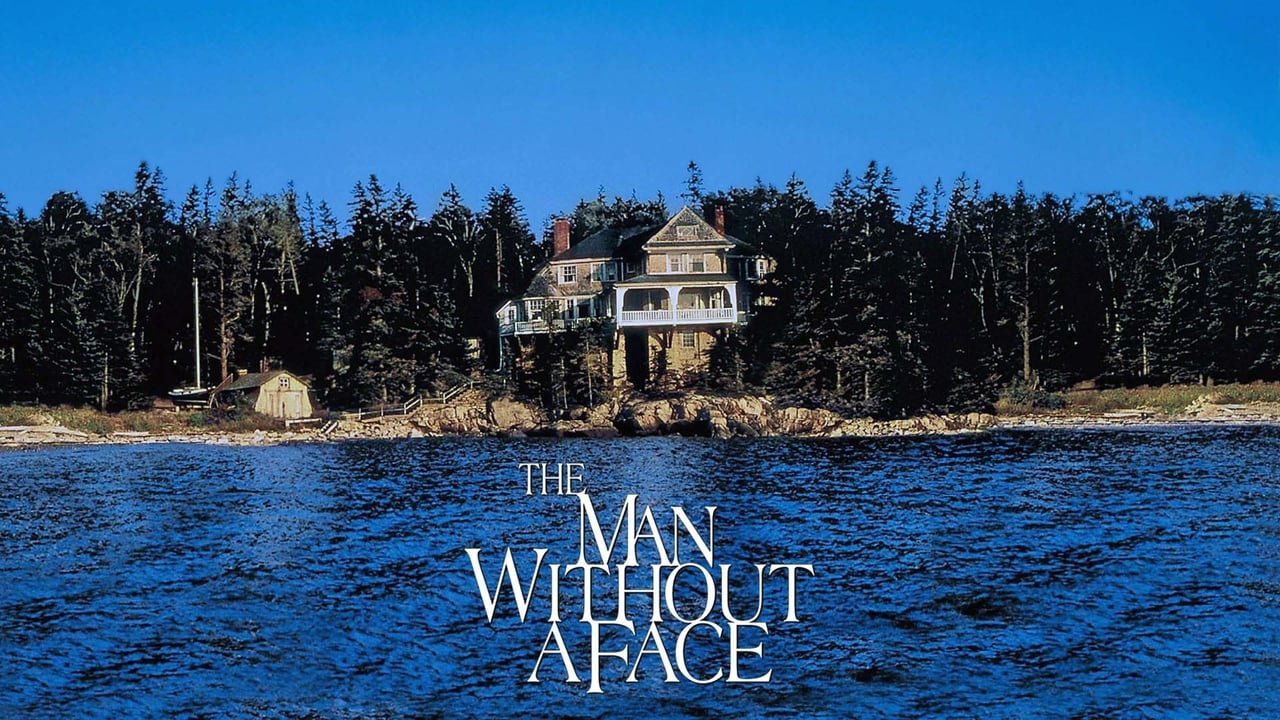

The film transports us to a coastal Maine town, steeped in the kind of picturesque tranquility that often hides simmering secrets and prejudices. Here lives Justin McLeod (Mel Gibson), a former teacher living in self-imposed exile, his face heavily scarred from a past accident, his reputation shrouded in rumour and suspicion. Into his orbit comes young Charles "Chuck" Norstadt (Nick Stahl), a bright but rudderless boy desperate to escape his dysfunctional family and pass the entrance exam for a prestigious military academy. Chuck sees McLeod not as the town pariah, but as a potential mentor, a lifeline. Their ensuing relationship, a clandestine tutoring arrangement held in McLeod's secluded home, forms the heart of this quietly compelling narrative.

Beyond the Scars

What unfolds isn't a simple teacher-student story. Gibson, directing with a surprising sensitivity for a first-timer, allows the relationship between McLeod and Chuck to develop organically. It's built on shared intellectual curiosity, mutual need, and a gradual dismantling of preconceived notions. McLeod, initially gruff and resistant, finds purpose in guiding Chuck, while Chuck finds in McLeod the stability, intellectual challenge, and genuine attention absent from his chaotic home life. The film asks us to look beyond McLeod's disfigurement, a potent visual metaphor for societal judgment based on appearance. How often do we form opinions based on surfaces, on whispers and conjecture, rather than seeking the truth of the person within?

Gibson's performance as McLeod is remarkably restrained. Stripped of his usual charismatic swagger, he embodies a man weary of judgment, finding solace in isolation yet yearning for connection. The physical transformation is striking – the intricate makeup effects, reportedly taking hours to apply each day, create a visceral sense of McLeod's past trauma. But it’s Gibson's nuanced portrayal of McLeod's inner life – the guarded warmth, the flashes of old pedagogical passion, the deep well of sadness – that truly anchors the film. He allows the silence and the stillness to speak volumes.

Equally impressive is the young Nick Stahl as Chuck. It's a breakout role, demanding a complex blend of adolescent angst, intellectual hunger, and vulnerability. Stahl holds his own opposite Gibson, conveying Chuck's yearning and resilience with an authenticity that feels raw and believable. Their scenes together crackle with intellectual energy and burgeoning trust, forming the undeniable core of the film's emotional power. Watching them navigate the unconventional lessons – drawing inspiration from Shakespeare as readily as from observing nature – feels like eavesdropping on something genuine and meaningful.

Whispers and Reckonings

Of course, this being a drama grounded in realism, the outside world inevitably intrudes. The small-town suspicion surrounding McLeod never fully dissipates, fueled by gossip and fear of the unknown. The film, based on Isabelle Holland's 1972 novel, navigates these potentially thorny themes with a measured hand, focusing primarily on the impact these accusations have on the central relationship. Some viewers might find the resolution slightly neat, perhaps softening some of the book's harder edges, but the emotional weight carried by Gibson and Stahl ensures the climax still resonates. It forces a confrontation not just between characters, but within the audience, challenging our own assumptions about truth, reputation, and the complexities of human connection.

Gibson's direction, while not flashy, demonstrates a keen eye for atmosphere and character. He uses the Maine locations effectively, the rugged coastline mirroring McLeod's own isolated existence. There's a patience to the storytelling, allowing moments to breathe, letting the weight of unspoken feelings settle. It’s a far cry from the kinetic energy of Lethal Weapon or the epic scale of Braveheart (1995), which would follow just two years later, proving Gibson’s versatility early on. It felt like a deeply personal project, reportedly one Gibson fought to make.

Lasting Impressions on Worn Tape

The Man Without a Face isn't a film that shouts its importance. It's a thoughtful, character-driven piece that relies on strong performances and a resonant central theme. Revisiting it now, decades after pulling that VHS tape from the shelf, its power lies in its quiet humanity. It reminds us of the profound impact a single relationship can have, the dangers of snap judgments, and the enduring need for understanding and acceptance. It's a film that perhaps resonated differently then, before Gibson's later career complexities, but judged purely on its own merits, it remains a surprisingly affecting and well-crafted directorial debut.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's powerful central performances, particularly from a young Nick Stahl, Gibson's sensitive direction in his first outing, and its thoughtful exploration of prejudice and mentorship. It avoids melodrama, creating a genuinely moving character study, even if the ending feels slightly conventional compared to the setup. It’s a standout 90s drama that earns its emotional weight.

What lingers most, perhaps, is the quiet dignity Gibson imbues in McLeod, and the fundamental question the film poses: can we ever truly see past the surface to the person hidden beneath?