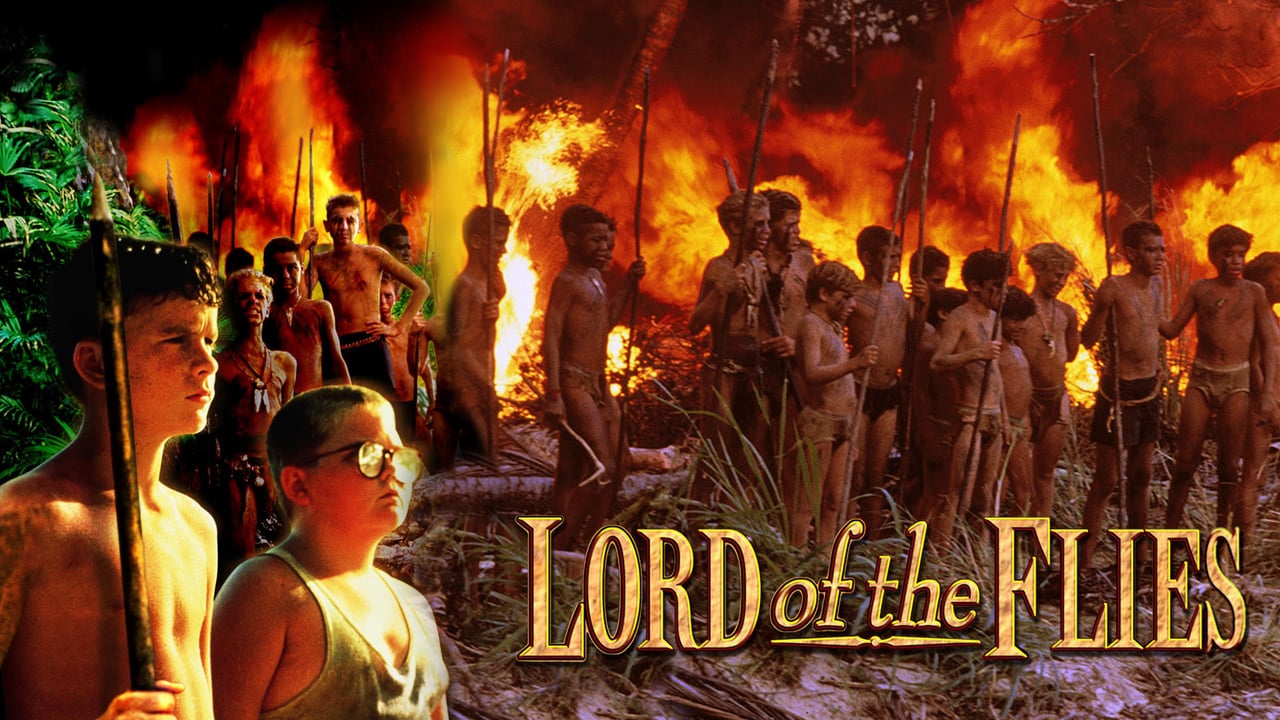

Okay, fellow tape travelers, let's rewind to a familiar, yet perhaps slightly less revered, corner of the video store shelf. There are certain stories so potent, so elemental, that they invite retelling across generations. William Golding's Lord of the Flies is undeniably one such tale, a harrowing exploration of the darkness lurking beneath the veneer of civilization. While Peter Brook's stark 1963 black-and-white adaptation often casts a long shadow, director Harry Hook's 1990 version, filmed in lush, deceptive color, offers its own distinct, and often unsettling, viewing experience – one many of us likely pulled from the ‘New Releases’ wall back in the day.

### Paradise Lost, Again

The premise remains terrifyingly simple: a plane crash strands a group of young American military cadets on a remote, uninhabited island. What begins as a desperate bid for survival, guided by the rational, elected leader Ralph (Balthazar Getty), soon devolves into primal savagery under the charismatic influence of the hunting-obsessed Jack (Chris Furrh). The conch shell, initially a symbol of order and democratic discourse, gradually loses its power, replaced by the chilling allure of the painted face and the tribal chant.

Hook’s decision, alongside screenwriter Sara Schiff (adapting Golding's novel), to make the boys American military cadets, rather than British schoolboys, subtly shifts the dynamic. Is there an inherent commentary here about a different kind of societal structure or discipline potentially masking the same underlying fragility? It adds a layer, though perhaps not always as effectively explored as it could be. The film leans more heavily into the visceral horror of the boys' descent, sometimes at the expense of the deeper allegorical resonance that defined the novel and the earlier film.

### Sun, Sand, and Savagery

Shot on location in picturesque Jamaica (specifically around Port Antonio, a detail perhaps lost on us during that first VCR viewing), the film uses its vibrant color palette to create a stark contrast. The turquoise waters and verdant jungle are postcard-perfect, making the escalating brutality feel even more jarring. It’s less the abstract nightmare of Brook’s vision and more a grounded, immediate horror. You feel the heat, the sweat, the encroaching chaos in a tangible way.

One can only imagine the challenges Hook faced, wrangling a large cast of relatively inexperienced young actors in such demanding conditions. The production reportedly cost around $9 million – a modest sum even then – and while it didn't set the box office alight (grossing just under $14 million worldwide), it certainly found a persistent life on home video. For many viewers my age, this was their introduction to Golding's chilling narrative.

### Faces in the Firelight

The weight of the film rests heavily on its young cast, and their performances are central to its impact, for better or worse. Balthazar Getty, already known to some from Young Guns II, brings a necessary vulnerability and growing desperation to Ralph. You see the burden of leadership weighing on him, the confusion as his appeals to reason fall on deaf ears. It's a performance grounded in a relatable sense of helplessness.

Opposite him, Chris Furrh as Jack is perhaps the film's most unsettling element. His transformation from disciplined cadet to savage hunter is genuinely chilling. There's a raw, almost feral energy to his performance that feels authentic, even if it occasionally borders on the theatrical. Does his descent feel earned, or slightly too rapid? That's a question that lingers.

And then there's Piggy, played with heartbreaking earnestness by Danuel Pipoly. Piggy represents logic, intellect, and the fragility of societal norms in the face of brute force. Pipoly captures his vulnerability, his intelligence, and his tragic fate with a sincerity that resonates long after the credits roll. It's a performance that cuts through some of the film's broader strokes. Watching him cling to the rules, to the significance of the conch, while everything falls apart around him… doesn't that echo anxieties we still grapple with today?

### Echoes on a Desert Island

While this 1990 Lord of the Flies might lack the haunting, poetic quality of the 1963 version for cinephiles, it possesses a directness, a blunt force, that arguably makes the story accessible, perhaps even more immediately shocking, to a different audience. It doesn't shy away from the violence, making the loss of innocence feel stark and brutal. The practical effects, typical of the era, convey the dangers – the pig hunts, the escalating conflict – with a physicality that grounds the allegory in a grim reality.

Was it the definitive adaptation? Probably not. Does it effectively convey the core horror of Golding's timeless warning about human nature? For many who rented this tape, perhaps encountering the story for the first time, the answer was likely a resounding, if uncomfortable, yes. It served as a gateway, a visceral translation of a powerful idea.

Rating: 6/10

Justification: While visually striking and featuring committed performances (particularly from Pipoly), Hook's adaptation sometimes sacrifices nuance for shock value. The shift to military cadets isn't fully explored, and it can't escape comparison to the more profound 1963 film. However, its raw energy and accessibility made it a significant VHS-era encounter with a crucial story, justifying its place slightly above average.

Final Thought: Even if flawed, this version forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth Golding laid bare: paradise is no protection from the darkness we carry within ourselves. What part of Ralph, Jack, or Piggy do we recognize most readily when the pressure mounts?