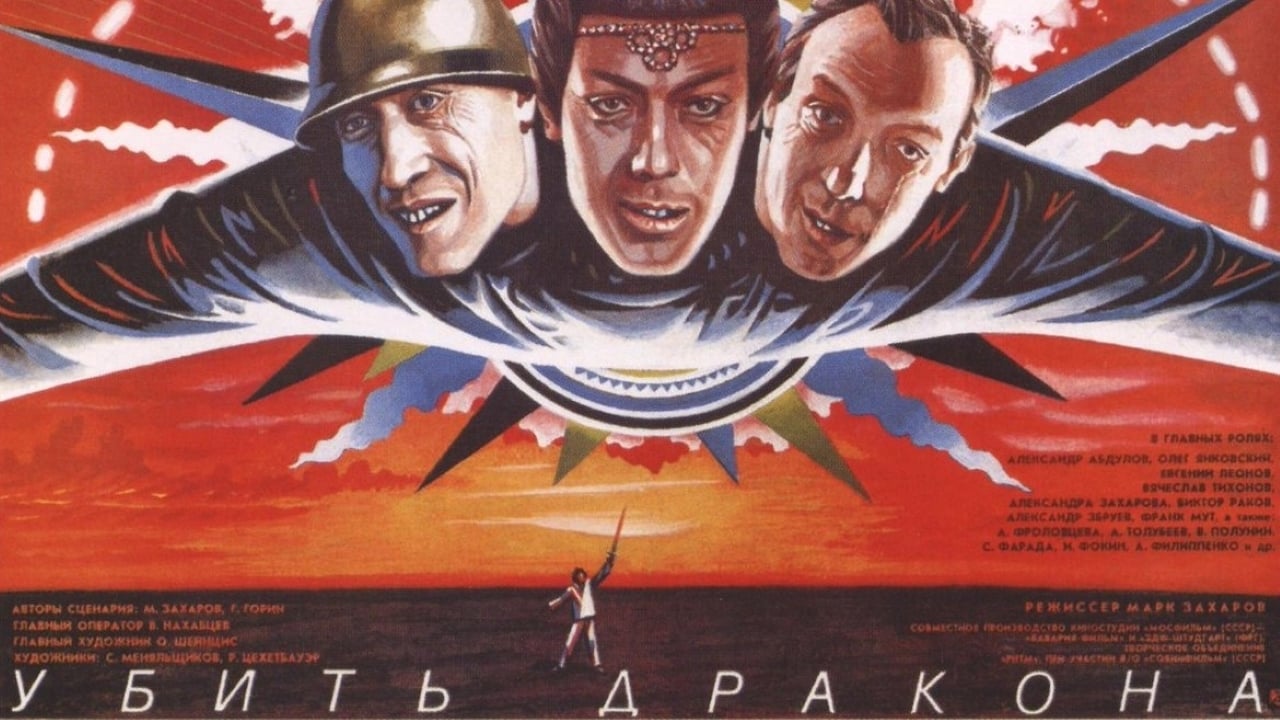

Here we delve into a film that might have been a more obscure find on the video store shelves, nestled perhaps between epic fantasies and historical dramas, yet offering something far stranger and more profound. Mark Zakharov's 1988 Soviet-German co-production, To Kill a Dragon (Ubit drakona), isn't your typical knights-and-princesses affair. It uses the trappings of a fairy tale to launch a blistering, darkly comedic, and ultimately chilling critique of tyranny and the complicity that allows it to flourish. This is one of those tapes you might have rented on a whim, drawn by the fantastical premise, only to find yourself grappling with its unsettling questions long after the VCR clicked off.

### More Than Just Scales and Fire

The setup feels familiar enough: the wandering knight Lancelot (Aleksandr Abdulov) arrives in a grim, perpetually grey town ruled for 400 years by a tyrannical Dragon (Oleg Yankovsky). The townspeople live in a state of weary resignation, accepting the Dragon's arbitrary cruelty and the annual sacrifice of a young maiden as immutable facts of life. Lancelot, brimming with heroic ideals, declares his intention to slay the beast and liberate the town. But To Kill a Dragon swiftly dismantles heroic simplicity. The Dragon isn't just a monster; he's a sophisticated, manipulative entity deeply embedded in the town's psyche. And the townspeople? They aren't exactly yearning for freedom.

Based on a 1944 play by Evgeny Schwartz, itself a sharp allegory penned under Stalinist censorship, Zakharov's film updates the satire for the era of Glasnost and Perestroika. The source material's troubled history – Schwartz's play was banned after only a few performances – adds a layer of historical weight. You can feel the legacy of suppressed commentary bubbling beneath the surface. It’s fascinating to think this film, co-produced with West German studios like Bavaria Film, emerged from Mosfilm during such a transitional period in Soviet history. It feels both like a product of newfound openness and a cautionary tale born from decades of looking over one's shoulder.

### The Faces of Tyranny and Apathy

The performances are key to the film's allegorical power. Aleksandr Abdulov, a charismatic star often seen in more romantic or adventurous roles, perfectly embodies Lancelot's initial naivete and growing disillusionment. He looks the part of the hero, which makes his struggle against not just the Dragon, but the ingrained apathy of the populace, all the more poignant.

But it's Oleg Yankovsky as the Dragon who truly mesmerizes. Known for his intense, intellectual presence in films like Tarkovsky's Nostalghia, Yankovsky presents a multi-faceted villain. The Dragon isn't always monstrous; he appears in human form, sometimes charming, sometimes philosophical, sometimes utterly terrifying. He argues, reasons, and justifies his rule, suggesting that he merely gives the people what they subconsciously desire: order, predictability, freedom from the burden of choice. It's a chilling portrayal of how totalitarian power can rationalize itself.

And then there's Yevgeny Leonov as the Burgomaster. Leonov, beloved in Russia for his comedic roles and his voice work as Winnie-the-Pooh in the Soviet adaptation, is devastatingly effective here. His Burgomaster is a figure of cheerful subservience, embodying the bureaucratic complicity and self-preservation that enables tyranny. His seemingly benign presence makes the town's sickness feel commonplace, almost normal. It’s a masterclass in using an actor's established persona against type to profound effect.

### A Bleak Fairytale World

Director Mark Zakharov, primarily known for his work in theatre and television films often marked by satire (like The Very Same Munchhausen), brings a specific, almost theatrical sensibility to the film. The production design creates a world that is both fantastical and depressingly drab. The town feels perpetually shrouded in mist and gloom, its architecture a strange mix of medieval and vaguely industrial decay. It's a physical manifestation of the citizens' inner state.

The special effects, particularly the Dragon itself, are perhaps dated by today's standards, but possess a certain late-80s charm. There's a tangible quality to the practical effects and puppetry that CGI often lacks. More importantly, the film doesn't rely solely on spectacle. The horror here is psychological and political. The Dragon's true power isn't his fire breath, but his insidious influence on the human soul.

One fascinating production tidbit: the script, co-written by Zakharov and the brilliant satirist Grigori Gorin (who also worked with Zakharov on Munchhausen), reportedly went through several iterations, carefully navigating the boundaries of what could be said even in the relatively open atmosphere of the late 80s. The allegorical nature was, in itself, a form of protection.

### The Chilling Question

Spoiler Alert (Minor Conceptual Spoiler Ahead)!

The film's most potent, and arguably most famous, idea comes after Lancelot seemingly achieves his goal. Defeating the physical manifestation of the Dragon proves far easier than eradicating the "dragon" within the townspeople – and perhaps within himself. The film asks a deeply uncomfortable question: what happens when people become so accustomed to subjugation that they fear freedom? When the structures of oppression are removed, do people simply erect new ones in their place? Does killing one tyrant merely pave the way for another, perhaps one who looks disturbingly like the hero?

This theme – that the tendency towards authoritarianism lies not just in leaders but also within the led – elevates To Kill a Dragon beyond simple political commentary into a more profound exploration of human nature. It resonates uncomfortably, perhaps even more so today than when it was released. Remember watching this back then, expecting a straightforward fantasy, and being hit with that gut-punch of an idea? It certainly stuck with me.

### Final Thoughts

To Kill a Dragon is not an easy watch. It’s bleak, cynical, and its humor is as sharp and dark as obsidian. It doesn't offer comforting answers or triumphant heroism in the conventional sense. Yet, it's a powerful, intelligent, and visually distinct piece of filmmaking. For those of us who trawled the video store shelves looking for something different, something challenging, this was a rare find – a fairy tale that forced you to think, smuggled within a worn VHS box. Its examination of power, conformity, and the difficult, ongoing struggle for true freedom feels startlingly relevant.

Rating: 8/10

Justification: While its pacing can sometimes feel deliberate and its bleakness unrelenting, To Kill a Dragon is a masterfully crafted allegory boasting exceptional performances (especially from Yankovsky and Leonov) and profound thematic depth. Its unique blend of fantasy, satire, and political commentary, born from a specific historical moment but speaking to universal anxieties, makes it a standout and thought-provoking film from the era.

VHS Heaven Final Take: A challenging but essential slice of late-Soviet cinema, reminding us that the most fearsome dragons are often the ones we carry inside ourselves.