There's a certain kind of grey, overcast sky that feels unique to the Pacific Northwest, a persistent melancholy that can seep into the very bones of a story. It hangs heavy over Permanent Record (1988), not just as background weather, but as a tangible presence, an atmospheric shroud wrapping itself around a group of vibrant high school students whose world is about to be irrevocably fractured. This isn't the bright, synthesized pop landscape of many beloved 80s teen flicks; it's something quieter, more somber, and ultimately, far more resonant.

Before the Silence

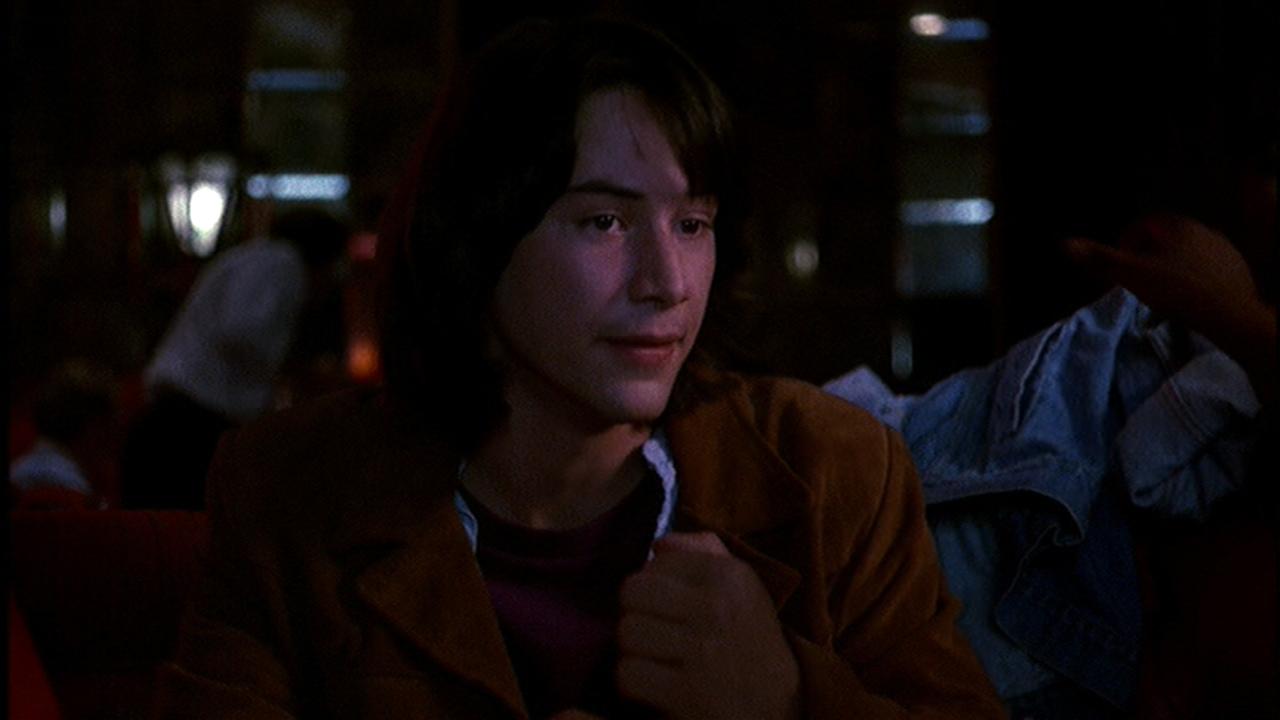

The film initially introduces us to a circle of friends seemingly on the cusp of everything. At its heart is David Sinclair, played with an almost unnerving charisma by the late Alan Boyce. David is the golden boy: effortlessly talented, academically brilliant, musically gifted, loved by everyone, especially his best friend Chris Townsend (Keanu Reeves). Their band is gaining local traction, college acceptances are rolling in, and the future looks like an open road. Director Marisa Silver, known more for her art-house sensibilities (like her earlier film Old Enough from 1984), paints this early picture with warmth, capturing the easy camaraderie, the shared dreams, and the specific anxieties of impending adulthood. We see the casual intimacy of late-night rehearsals, the nervous energy before a gig, the hopeful glances exchanged between David and his girlfriend Lauren (Jennifer Rubin). It feels authentic, lived-in.

The Unthinkable Ripple

And then, without fanfare, without melodrama, the unthinkable happens. David, the boy who seemed to have it all, takes his own life. Spoiler Alert! (Though the film's core premise hinges on this). The way Permanent Record handles this seismic event is perhaps its greatest strength. There’s no sensationalism, no drawn-out suspense. It’s presented as a sudden, devastating fact, leaving his friends and community reeling in bewildered silence. The film shifts its focus primarily to Chris, and it’s here that Keanu Reeves, in one of his earliest and most affecting dramatic roles, truly anchors the narrative. His portrayal of Chris’s grief isn't loud or performative; it’s a study in stunned disbelief, quiet anger, and a desperate, fumbling search for answers that simply aren’t there. Remember seeing Reeves in Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure around the same time? The contrast highlights his range even then; here, the characteristic stillness he often employs becomes a powerful conduit for suppressed agony.

Searching for Meaning in the Static

What follows isn't a mystery to be solved, but an exploration of the messy, confusing aftermath. Chris becomes obsessed with finding David's final musical composition, believing it holds the key to understanding why. His friends grapple with their own guilt, sadness, and the uncomfortable questions David’s death forces upon them. Jennifer Rubin brings a poignant vulnerability to Lauren, navigating her own loss while trying to connect with a grieving Chris who keeps pushing everyone away. The adults – parents, teachers – are portrayed not as clueless antagonists, but as equally lost, struggling to offer comfort or explanation in the face of inexplicable tragedy. The film doesn't offer easy answers or platitudes about suicide. Instead, it sits with the discomfort, the confusion, the anger, and the profound sense of absence. Doesn't this raw honesty feel rare, even brave, for a mainstream-adjacent teen film from that era?

Behind the Grey Skies

Shot on location in Portland and Yaquina Head, Oregon, the film uses its setting masterfully. The overcast skies, the rugged coastline – it all contributes to the pervasive mood of introspection and sorrow. It’s a visually grounded film, favouring realism over stylized gloss. Interestingly, the soundtrack, often a driving force in 80s movies, here serves a more reflective purpose. While featuring contributions from artists like The Stranglers, Lou Reed, and notably Joe Strummer of The Clash (whose involvement adds a certain punk-rock melancholy), the music underscores the emotion rather than dictating it. It wasn't a chart-topping soundtrack album designed to sell records; it felt curated to serve the film's somber tone. Tackling youth suicide so directly was undoubtedly a challenge in 1988, and Marisa Silver navigates it with sensitivity, focusing on the emotional fallout rather than the act itself, a choice that lends the film its lasting power. It reportedly performed modestly at the box office, perhaps proving too heavy for audiences seeking lighter escapism, but its impact lingered for those who caught it on VHS, discovering a teen drama with unusual depth.

Permanent Record isn't a film about finding closure, because often, there isn't any. It’s about learning to carry the weight of loss, about the indelible marks left on us by those we love, and about the frightening realization that sometimes, we never truly know the inner lives of even those closest to us. It captures the way tragedy can suddenly redraw the map of your world, leaving you stranded in unfamiliar territory.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's courageous handling of a difficult subject, its evocative atmosphere, and particularly the powerful, understated performances from Keanu Reeves and Alan Boyce. It avoids melodrama, opting for a quiet authenticity that feels truthful, even decades later. While perhaps not as polished or widely remembered as some contemporaries, its emotional honesty earns it a significant place.

It's a film that stays with you, a somber melody echoing long after the tape clicks off, reminding us that some records, etched onto our hearts, are indeed permanent.