It often begins with a detail, doesn't it? A fleeting image that lodges itself in the memory long after the screen goes dark. For Hou Hsiao-hsien's profoundly moving 1985 film, The Time to Live and the Time to Die (童年往事), it might be the image of the grandmother, perpetually lost, forever trying to walk back across the bridge to a mainland China that exists only in her fading recall. It's a quiet anchor in a film built from the silt of memory, a devastatingly patient exploration of growing up amidst loss, displacement, and the inexorable march of time.

This isn't your typical 80s fare, certainly not the kind of tape likely found nestled between action blockbusters at the front of the rental store. Discovering a film like this back then, perhaps on a specialty label VHS or through a university film society screening, felt like uncovering a hidden frequency, a different way movies could speak. It demanded a stillness from the viewer, a willingness to observe rather than simply watch. And the rewards? Immeasurable.

A Childhood Remembered, Not Relived

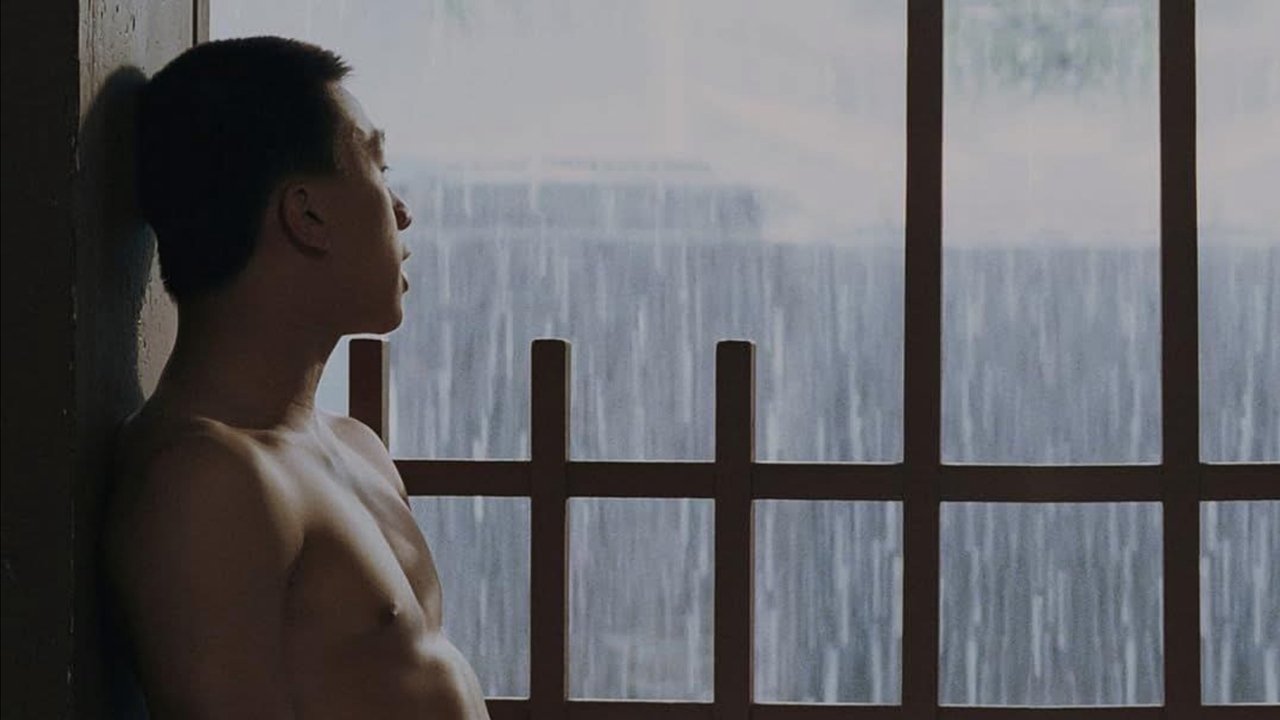

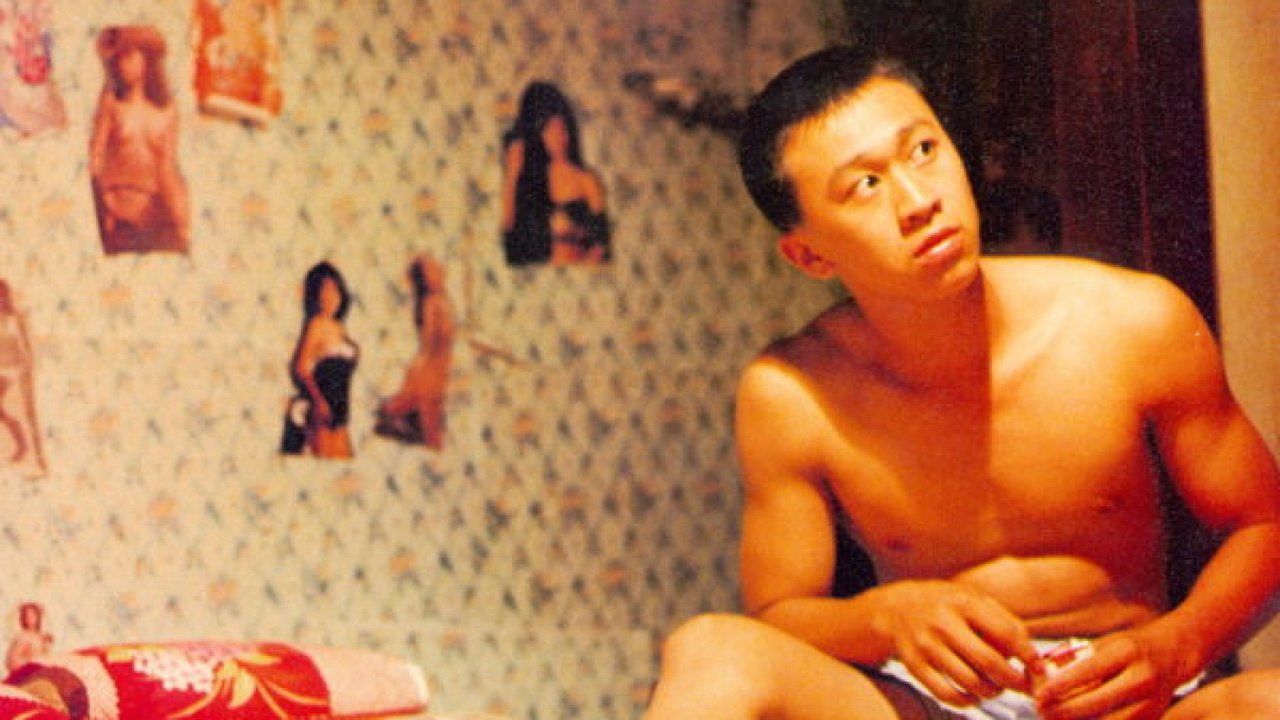

Director Hou Hsiao-hsien, a central figure in the Taiwanese New Wave cinema movement alongside contemporaries like Edward Yang (Yi Yi, 2000), draws deeply from his own childhood experiences here. The film follows Ah-ha (played at different ages, notably by Yu An-shun as the adolescent) and his family, mainlanders who relocated to rural Taiwan following the Chinese Civil War. We witness life through his eyes: the rough-and-tumble games with neighborhood kids, the simmering tensions and quiet affections within the family, the confusing stirrings of adolescence, and, most poignantly, the successive losses of his grandmother, father (Tien Feng, radiating weary authority), and mother (Mei Fang, embodying quiet resilience).

Hou's approach is distinct. Forget rapid cuts and overt exposition. He favours long, often static takes, observing moments with an almost painterly composition. The camera frequently keeps its distance, placing characters within their environment, letting the landscape and the architecture speak volumes about their lives and limitations. This isn't about recreating events with dramatic flair; it's about capturing the feeling of memory, the way certain mundane details linger while significant events can feel strangely muted or observed from afar. It’s a style that requires patience, yes, but it fosters an incredible intimacy, allowing the weight of unspoken emotion to accumulate.

Echoes in the Silence

The performances are remarkable for their naturalism. Many of the actors were non-professionals or chosen for their authentic presence rather than star power. Tang Yu-Yuan as the grandmother is unforgettable; her senility isn't played for laughs or pathos, but as a simple, heartbreaking fact of life, her refrain of needing to go "home" a constant, tragic reminder of the family's displacement. Tien Feng embodies the patriarch burdened by failing health and the weight of exile, his authority slowly waning. Mei Fang conveys the mother's deep love and sorrow through subtle gestures and expressions. And young Yu An-shun navigates Ah-ha's journey from boisterous child to troubled, grieving adolescent with a quiet intensity that feels utterly true. There's no melodrama; the grief is often internalised, glimpsed in a turned back, a long silence, or a sudden, shocking outburst of youthful frustration or violence.

More Than Just a Family Story

While deeply personal – Hou has confirmed the film is largely autobiographical – The Time to Live and the Time to Die transcends the specific. It becomes a meditation on universal experiences. Who hasn't felt the bewildering confusion of adolescence, the sharp pang of losing a loved one, the sense that time is slipping away too quickly? The film captures the specific historical context of Taiwanese identity and the complex relationship with mainland China, but its core concerns – family bonds, mortality, the formation of self – resonate across cultures and generations.

It’s fascinating to consider this film emerging in the mid-80s, an era often defined by excess in Western cinema. Hou’s minimalism and focus on everyday realism offered a powerful counterpoint. There's a story, possibly apocryphal but illustrative, that Hou would sometimes set up a shot and then leave the set, trusting his actors and the environment to create the necessary truth within the frame. Whether strictly accurate or not, it speaks to the film's profound trust in observation and its rejection of directorial manipulation. It’s about letting life unfold, in all its quiet beauty and sorrow.

The Lingering Resonance

What stays with you? The light filtering through wooden slats. The sound of rain on a tin roof. The awkward fumblings of teenage courtship. The stark, almost unbearable quiet after a death. Hou masterfully uses the seemingly ordinary to build extraordinary emotional weight. It's a film that doesn't shout its themes but lets them seep into your consciousness, leaving you contemplative long after the credits roll. It makes you consider your own family, your own passage through time, the moments that define us, both the grand and the quietly mundane.

Rating: 9/10

This rating reflects the film's masterful direction, its profound emotional honesty, and its significance within world cinema. The deliberate pacing and observational style might not be for everyone, but for those willing to engage with its quiet rhythms, The Time to Live and the Time to Die offers an exceptionally rich and moving experience. It avoids sentimentality, achieving instead a deep, earned poignancy through its unflinching yet compassionate gaze.

It's a reminder that cinema can be more than just entertainment; it can be a vessel for memory, empathy, and quiet contemplation – a truth that feels just as vital today as it did when these images first flickered onto screens back in 1985. This film doesn't just show a life; it lets you feel the texture of it.