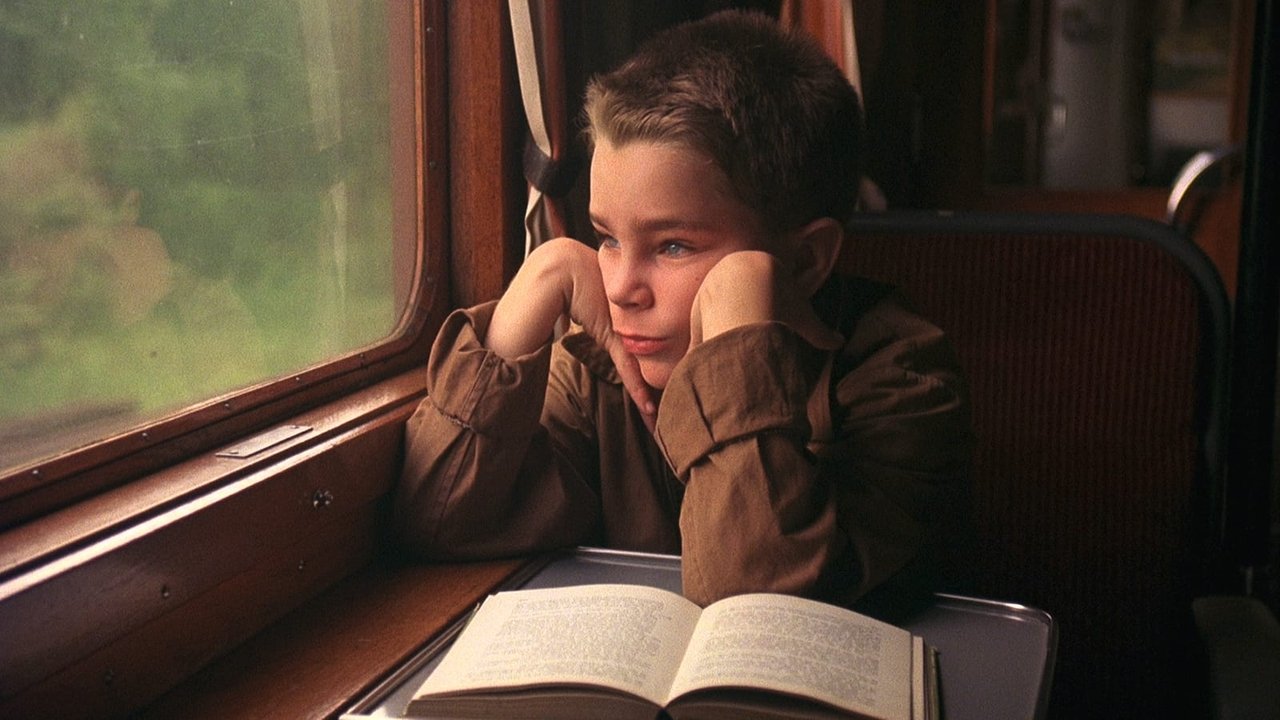

There's a recurring image in Lasse Hallström's My Life as a Dog (Swedish: Mitt liv som hund) that lodges itself firmly in the viewer's mind long after the credits roll: a young boy, Ingemar, contemplating the fate of Laika, the Soviet space dog sent into orbit with no plan for return. "You have to compare," he tells himself, wrestling with his own childhood traumas – a dying mother, separation from his beloved dog, the chaotic energy of burgeoning adolescence. It’s this constant, quiet act of seeking perspective, however flawed or childish, that elevates this 1985 Swedish gem beyond a simple coming-of-age story into something profoundly human and enduringly resonant. Finding this on a video store shelf, perhaps tucked away in the foreign film section, felt like uncovering a secret whispered from across the ocean.

A Summer of Change

The setup is deceptively simple. Twelve-year-old Ingemar (Anton Glanzelius) is a rambunctious, well-meaning boy whose antics often exacerbate the stress surrounding his mother's (Anki Lidén) terminal illness (likely tuberculosis, though never explicitly stated). To give her rest and shield him from the inevitable, Ingemar is sent away for the summer (and beyond) to stay with his Uncle Gunnar (Tomas von Brömssen) and Aunt Ulla (Anki Lidén) in a small rural village dominated by a glassworks factory. His beloved dog, Sickan, mirroring his own displacement, is sent elsewhere – a separation that weighs heavily on the boy. What unfolds isn't a grand drama, but a tapestry woven from small moments: quirky encounters, childhood discoveries, misunderstandings, and the first awkward stirrings of romance, all seen through Ingemar's watchful, processing eyes.

Through a Child's Looking Glass

What makes My Life as a Dog so captivating is Hallström's masterful direction, later showcased in Hollywood films like What's Eating Gilbert Grape (1993) and The Cider House Rules (1999). Here, in his international breakthrough, he adopts Ingemar's perspective without affectation or condescension. The camera often observes events with a child's curiosity, lingering on details an adult might miss, capturing the strange logic and emotional currents that define youth. The film never feels sentimental or manipulative; the sadness is real, but so is the genuine, often eccentric, joy found in the village community.

Crucial to this is the astonishingly natural performance by Anton Glanzelius. Reportedly chosen for his lack of acting experience, Glanzelius embodies Ingemar with an authenticity that feels less like acting and more like witnessing. His subtle shifts in expression, his moments of quiet contemplation juxtaposed with bursts of boyish energy, ground the film. He isn’t playing cute or precocious; he’s simply being a boy navigating a confusing, sometimes painful, world. It’s a performance that feels discovered rather than crafted, and it’s heartbreaking that Glanzelius largely stepped away from acting afterwards; his raw talent here is undeniable.

Village Life and Finding Bearings

The village itself becomes a character – populated by eccentrics like the green-haired, boxing-obsessed girl Saga (Melinda Kinnaman), who becomes Ingemar’s unlikely friend and rival, and Uncle Gunnar, whose rooftop readings of lingerie catalogues provide moments of gentle absurdity. These aren't caricatures but flawed, believable people finding their own ways to cope. The boxing matches with Saga, the shared fascination with a neighbour modelling nude for an artist, the collective awe over the "Blue Hawaii" record – these vignettes paint a picture of life continuing, vibrant and strange, even amidst personal grief.

It was this delicate blend of melancholy and offbeat humor that likely caught international audiences and critics by surprise. This modest Swedish production, based on the semi-autobiographical novel by Reidar Jönsson, became a significant arthouse hit in the US (grossing over $8 million – a remarkable sum for a subtitled film in the mid-80s) and earned Hallström Academy Award nominations for Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay. It proved that stories rooted in specific cultural contexts could possess universal emotional power, something many of us discovered hunting through those video store aisles for something different.

The Weight of Comparison

Ingemar’s mantra, "Things could have been worse," comparing his plight to accident victims or the doomed Laika, isn't about minimizing his pain. It’s a child's coping mechanism, an attempt to contextualize overwhelming feelings. Doesn't this resonate with how we all, at times, try to frame our own difficulties against the vastness of others' suffering? The film doesn't judge this impulse; it merely observes it with gentle empathy. It acknowledges the validity of Ingemar's sadness while simultaneously celebrating his resilience and capacity for finding connection and moments of happiness even when his world feels unstable.

What lingers most after watching My Life as a Dog isn't just the sadness of Ingemar's situation, but the quiet strength he finds, the way life’s peculiar rhythms offer unexpected solace. It’s a film that understands that laughter and tears often occupy the same space, especially in childhood.

Rating: 9/10

This rating reflects the film's exceptional emotional depth, the unforgettable lead performance, and Hallström's sensitive, nuanced direction. It avoids sentimentality while delivering genuine pathos and capturing the bittersweet nature of growing up with startling authenticity. It loses perhaps a single point only in that its episodic nature might feel slightly meandering to some viewers expecting a more conventional plot trajectory, but this very quality is also part of its unique charm and realism.

My Life as a Dog remains a profoundly moving piece of cinema, a quiet triumph that reminds us of the complex inner lives of children and the strange, often beautiful ways we find to navigate the world. It's more than just a foreign film curiosity from the VHS era; it’s a timeless exploration of resilience, perspective, and the enduring power of human connection, even when you feel as lost as a dog shot into space.