Alright, fellow tapeheads, let's rewind to that glorious, slightly grimy era of the late 90s video store. Remember scanning the shelves, past the bright family comedies and explosive action flicks, and landing on that box? The one that hinted at something darker, maybe a little dangerous? For many of us, that was the magnetic pull of 1998's Very Bad Things. This wasn't your average feel-good rental, folks. This was the cinematic equivalent of finding a cursed artifact disguised as a party invitation.

The Hangover from Hell

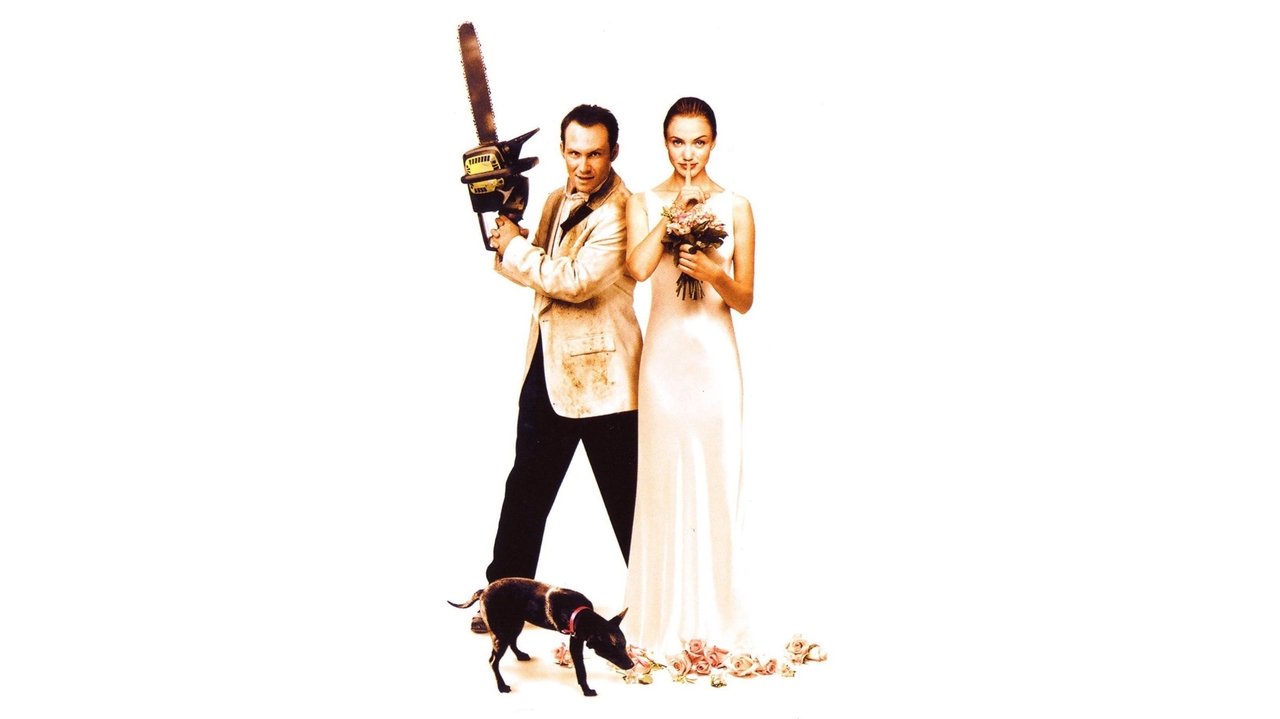

Before The Hangover (2009) made bachelor party chaos mainstream funny, actor-turned-director Peter Berg (Friday Night Lights, Lone Survivor) unleashed this pitch-black comedy/thriller as his directorial debut. The premise starts innocently enough: Kyle Fisher (Jon Favreau, hot off the indie success of Swingers (1996)) is heading to Vegas with his buddies for one last hurrah before marrying the meticulously demanding Laura (Cameron Diaz, in a role miles away from her sunny There's Something About Mary persona from the same year). His crew includes the volatile alpha male Robert Boyd (Christian Slater, absolutely chewing the scenery), the anxious Michael (Jeremy Piven), the mild-mannered Adam (Daniel Stern), and Adam's meek brother Charles (Leland Orser, mastering quiet desperation). Booze flows, bad decisions are made, and then... well, the title isn't kidding. An accidental death during a debauched moment with a stripper sends the group spiraling into a vortex of panic, paranoia, and increasingly horrific choices.

No Turning Back Now

What makes Very Bad Things burrow under your skin, even decades later, is its relentless commitment to the downward spiral. There's no easy way out, no moment of convenient redemption. Berg's script keeps tightening the screws, forcing these increasingly desperate men into situations that are simultaneously appalling and darkly funny. You watch through splayed fingers as one catastrophic decision piles onto another. Remember that feeling, watching on a flickering CRT, the grainy VHS picture almost enhancing the sordidness? The film captures that late-night, slightly illicit viewing vibe perfectly. It felt wrong to laugh, but the sheer absurdity of their escalating predicament often forced a shocked chuckle.

One fascinating bit of trivia: Berg was reportedly inspired, in part, by a disturbing real-life story he'd heard, which perhaps explains the film's refusal to soften its edges. It wasn't designed to be comfortable. It aimed to provoke, and boy, did it succeed. Critically divisive upon release and a box office disappointment (making only about $21 million worldwide against a $30 million budget), it nonetheless carved out a niche as a cult favorite precisely because it dared to go so dark.

That Raw 90s Intensity

Let's talk about the "action" here. It’s not Stallone mowing down armies, but the visceral consequences of terrible choices. The initial accident is sudden, brutal, and depicted with a starkness that feels distinctly pre-CGI slickness. When things get violent later – and they really do – there's a messy, unpolished quality to it. Think less balletic choreography, more panicked flailing and grim, tangible results. It leans into the ugliness, using practical effects not for spectacle, but for impact. Remember how those moments felt genuinely shocking back then, lacking the digital buffer we often see today? That rawness is key to the film's queasy power.

Slater Unleashed, Favreau Unraveling

The ensemble cast is crucial. Favreau is excellent as the increasingly frayed groom-to-be, the everyman anchor slowly drowning in the nightmare. Stern and Piven provide different shades of panicked reactions. But it's Christian Slater as Boyd who often steals the show. He’s the catalyst, the disturbingly charismatic voice of nihilistic pragmatism pushing them deeper into the abyss. His energy is manic, almost gleeful in its amorality – a classic late-90s Slater performance cranked up to eleven. And Cameron Diaz? Her Laura isn't just a Bridezilla; she becomes something far more chilling as the plot unfolds, revealing a terrifyingly pragmatic core beneath the wedding planning obsession.

Beyond the Shock Value

Is Very Bad Things just empty provocation? I don't think so. Beneath the gore and grim humor, it’s a savage commentary on toxic masculinity, peer pressure, and the terrifying ease with which civility can collapse under duress. It explores how quickly "regular guys" can rationalize monstrous acts when trapped. It’s uncomfortable, yes, but it lingers because it taps into primal fears about losing control and facing the consequences of our worst impulses. It’s the kind of film that sparked heated debates after the credits rolled on that worn-out tape.

Rating: 7/10

Why this score? Very Bad Things isn't perfect. Its relentless darkness can be overwhelming, and some might find the humor too mean-spirited. It definitely alienates as many viewers as it captivates. However, for its audacity, its committed performances (especially Slater and Favreau), Berg's uncompromising direction in his debut, and its status as a truly edgy artifact of late 90s cinema, it earns a solid 7. It’s a film that takes risks, even if they don’t all land comfortably.

Final Take: This is pure, uncut, late-90s nihilistic chaos captured on magnetic tape. If you fondly remember renting those boundary-pushing flicks that made you squirm and maybe question your own moral compass, Very Bad Things remains a potent, if deeply uncomfortable, trip down a very dark memory lane. Just maybe don't watch it right before a wedding.