### The Saxophone Player Who Lost His Country, But Found Himself

There's a certain kind of quiet performance that stays with you long after the tape has rewound with a satisfying clunk. It's not about explosive moments, but the slow burn of internal realization, the subtle shifts in expression that speak volumes. Thinking back on Paul Mazursky's Moscow on the Hudson (1984), what resonates most profoundly, decades later, isn't just the Cold War backdrop or the fish-out-of-water comedy, but the astonishingly grounded and deeply felt performance by Robin Williams as Vladimir Ivanoff. For many of us who primarily knew Williams then for his whirlwind comedic energy on Mork & Mindy or his stand-up, this felt like seeing a familiar friend reveal a hidden, soulful depth.

A Different Kind of Defection Story

The film opens not with espionage or high drama, but with the mundane textures of life in the Soviet Union: the queues, the cramped apartments, the constant low-level anxiety, but also the camaraderie and dreams simmering beneath the surface. Vladimir is a saxophonist with the Moscow circus orchestra, yearning for simple freedoms – like buying Italian shoes without a three-day wait. When the circus troupe gets a rare chance to perform in New York City, the allure of the West becomes tangible, overwhelming. Mazursky, whose own grandparents were Russian Jewish immigrants, brings a palpable empathy to these early scenes. It wasn't just about portraying oppression; it was about showing the humanity caught within the system. We feel Vladimir's quiet frustration, his cautious hope, his love for his family weighing against his desire for something more.

Interestingly, the original script focused more heavily on the relationship between Vladimir and his KGB handler. However, Mazursky and co-writer Leon Capetanos shifted the focus towards Vladimir's personal journey and his experiences after arriving in America, making it less of a political thriller and more of a human drama – a choice that gives the film its lasting heart.

Bloomingdale's and Beyond

The film's pivotal moment, Vladimir's impulsive defection inside Bloomingdale's department store ("I defect!"), is handled brilliantly. It's chaotic, terrifying, and unexpectedly poignant. Williams conveys Vladimir’s panic and sudden resolve with breathtaking vulnerability. Mazursky reportedly chose Bloomingdale's as the location because it represented the ultimate symbol of American consumerism and overwhelming choice, a stark contrast to the scarcity Vladimir knew. Filming this scene required significant coordination, essentially taking over a section of the bustling store.

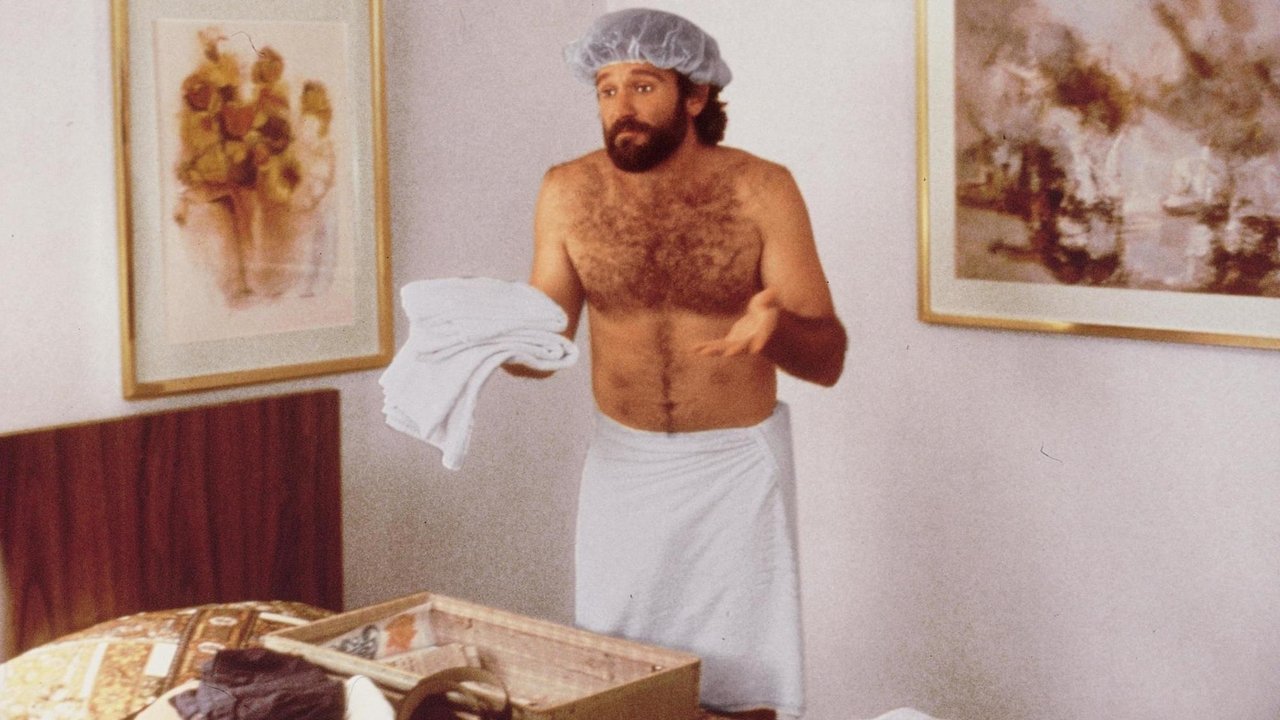

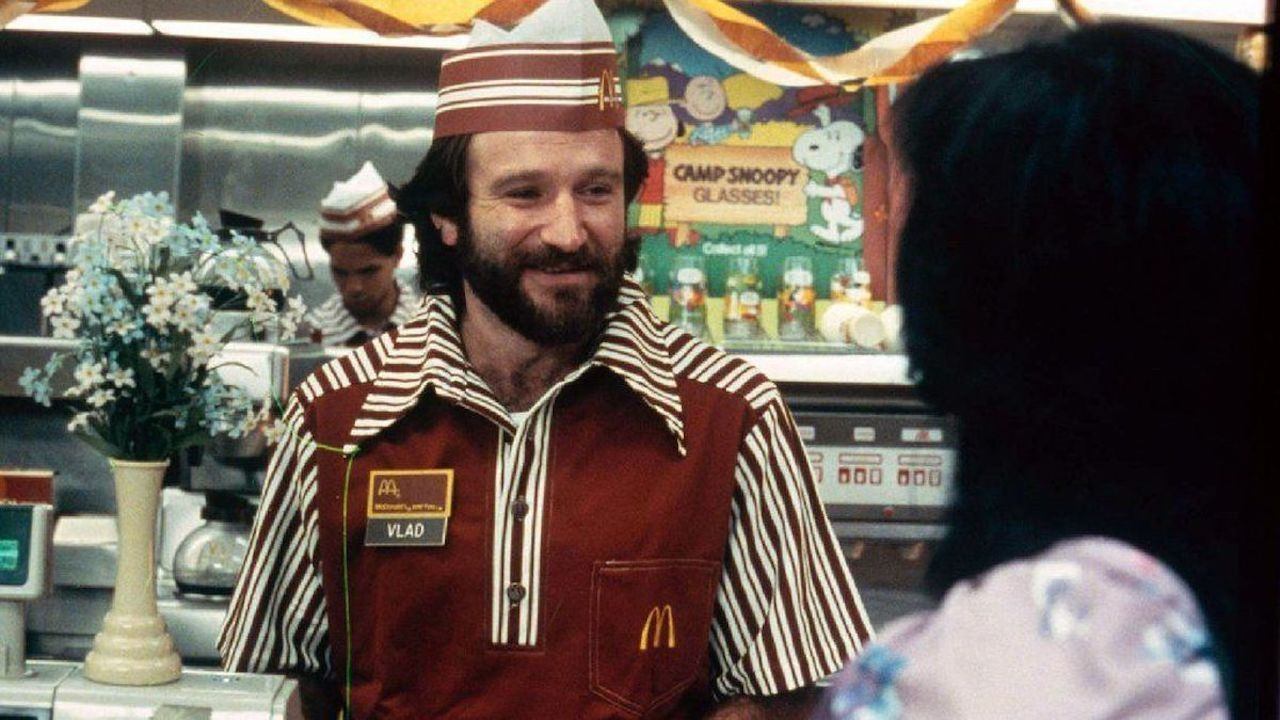

But the defection isn't the end; it's the beginning of a different struggle. Moscow on the Hudson excels in depicting the often unglamorous reality of starting over. Vladimir finds himself navigating the bewildering landscape of 1980s New York – the noise, the pace, the sheer muchness of it all. He finds support and friendship in unexpected places: Lucia Lombardo (María Conchita Alonso, in her vibrant American film debut), a pragmatic Italian immigrant working at Bloomingdale's, and Lionel Witherspoon (Cleavant Derricks, radiating warmth and street smarts), a security guard who becomes Vladimir's first real anchor in this new world. Their interactions provide much of the film's warmth and humor, but it’s always grounded in the characters' experiences. Alonso, herself an immigrant from Cuba via Venezuela, brought an undeniable authenticity to Lucia’s blend of toughness and tenderness.

Freedom Isn't Simple

What makes Moscow on the Hudson endure is its refusal to offer easy answers. Freedom, the film suggests, isn't just parades and prosperity; it's also loneliness, confusion, and the ache of missing home. Vladimir experiences racism, economic hardship, and the baffling complexities of American bureaucracy. There's a particularly moving scene where he finally gets his beloved saxophone back, only to find the joy tinged with the melancholy of his displacement. Doesn't this resonate with the immigrant experience across generations – the bittersweet trade-offs that come with seeking a new life?

Williams’s commitment to the role was total. He spent months learning Russian – enough to handle his dialogue convincingly – and also learned to play the saxophone. It wasn't about mimicry; it was about inhabiting Vladimir's skin. His performance is a masterclass in subtlety. Watch his eyes in the quieter scenes – the longing, the fear, the cautious flicker of hope. It’s a performance built on observation and empathy, worlds away from the manic improvisations he was famous for. It earned him a Golden Globe nomination and signaled the dramatic powerhouse he would continue to reveal in films like Good Morning, Vietnam (1987) and Dead Poets Society (1989).

A Time Capsule with a Timeless Heart

Watching Moscow on the Hudson today feels like opening a time capsule. The specific Cold War anxieties, the look of early 80s New York, the very presence of Bloomingdale's as a cultural epicenter – it’s all deeply nostalgic. I recall renting this on VHS, probably from some long-gone local video store, struck even then by how it balanced humor and sadness without feeling forced. It wasn't just a comedy about a Russian defector; it felt like a genuine story of a human being navigating immense change.

The film wasn't a massive blockbuster (grossing around $25 million on a $13 million budget), but it found its audience, particularly those drawn to Williams's departure and Mazursky's gentle, humanistic touch. It remains a thoughtful, often funny, and ultimately moving portrait of the immigrant experience, anchored by a career-defining performance.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's heartfelt storytelling, Robin Williams's exceptional and nuanced performance, and its sensitive handling of complex themes like freedom, displacement, and the search for belonging. While perhaps a touch slow in places by modern standards, its emotional honesty and Mazursky's empathetic direction make it a standout from the era. It earns its place not just as a piece of 80s nostalgia, but as a genuinely affecting piece of cinema.

What lingers most is the film's quiet understanding that finding freedom doesn't erase the past, but reshapes the future in ways both beautiful and challenging. It’s a reminder that behind geopolitical headlines, there are always individual human stories waiting to be told.