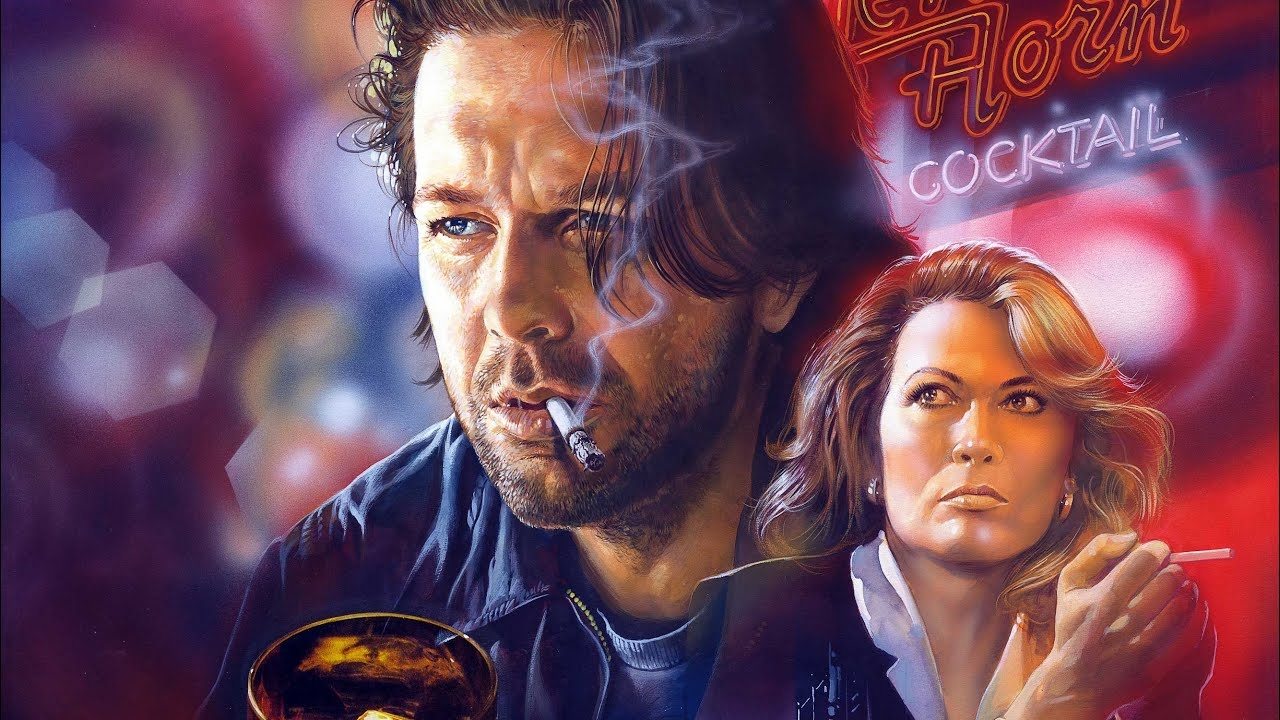

There's a particular kind of quiet that settles over a certain type of bar late at night, or maybe early in the morning – the kind where the regulars seem fused to their stools and the air hangs thick with unspoken stories. Capturing that specific, slightly desperate poetry is where Barbet Schroeder’s Barfly (1987) truly excels. This isn't a film that bursts onto the screen; it shuffles in, orders a drink, and fixes you with a knowing, bloodshot gaze. Watching it again, decades after first sliding that well-worn VHS tape into the VCR, feels less like revisiting a movie and more like stepping back into that smoky, dimly lit world.

The Poet of the Gutters

At its heart, Barfly is pure Charles Bukowski. The legendary counter-culture poet penned the screenplay himself, based loosely (or perhaps not so loosely) on his own booze-soaked years navigating the dive bars and flophouses of Los Angeles. It’s a semi-fictionalized account, with Bukowski’s alter-ego, Henry Chinaski, brought to life in a performance that remains astonishing. There’s an undeniable authenticity here, a refusal to romanticize or sanitize the grit and grime of Henry’s existence. Bukowski famously had a long and arduous journey getting this script made, bouncing around Hollywood for years before finding unlikely champions in Cannon Films, the studio better known for Chuck Norris action flicks than poetic character studies. Keep an eye out during one of the bar scenes – Bukowski himself is there, nursing a drink, a quiet observer in his own cinematic world.

Rourke's Astonishing Metamorphosis

You simply cannot discuss Barfly without focusing on Mickey Rourke's staggering transformation into Henry Chinaski. This was 1987, and Rourke was still a charismatic leading man, familiar from films like Diner (1982) and the controversial 9½ Weeks (1986). Here, he’s almost unrecognizable. It’s not just the greasy hair, the perpetual stubble, or the ill-fitting clothes; it’s the profound physical embodiment of the character. Rourke adopts a hunched posture, a slow, deliberate shuffle, and a slurred, mumbling speech pattern that feels utterly lived-in. He reportedly spent time studying Bukowski's mannerisms and even endured cracked ribs while filming one of the film's raw, realistic alley brawls, eschewing stunt doubles. Whether method acting myth or reality, the result is undeniable: Rourke disappears, and Henry Chinaski stands before us – cynical, surprisingly gentle, dedicated solely to his writing and his next drink. What does this level of dedication reveal about an actor's drive to truly become someone else on screen?

A Dance of Desperation

Matching Rourke's intensity is Faye Dunaway as Wanda Wilcox, a fellow lost soul who becomes Henry’s lover and drinking companion. Dunaway, decades removed from her iconic turns in Chinatown (1974) and Network (1976), delivers a performance of shattering vulnerability. Wanda is beautiful but broken, clinging to a faded glamour that the harsh fluorescent lights of the bar can’t quite extinguish. There’s a weariness in her eyes, but also a flicker of defiance, a desperate need for connection that draws her to Henry’s orbit. Their relationship is messy, volatile, and strangely tender – two damaged people finding a temporary, booze-fueled solace in each other’s company. Dunaway earned a Golden Globe nomination for this role, seen by many as a powerful comeback, proving her extraordinary range remained undimmed. The chemistry between Rourke and Dunaway isn't conventionally romantic; it's something far more complex and raw, a shared understanding forged in the crucible of addiction.

Capturing the Atmosphere

Director Barbet Schroeder, who had previously directed documentaries and the compelling General Idi Amin Dada (1974), brings a stark, unvarnished realism to the proceedings. He reportedly fought fiercely to get the film made, even – according to legend – threatening self-mutilation to convince Cannon producers Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus of his commitment. Thankfully, it didn't come to that. Schroeder and cinematographer Robby Müller shoot the film without filters or gloss, letting the dingy bars (many of them actual LA dives used for location shooting) and cheap apartments feel palpable. The hum of neon signs, the clinking of glasses, the low murmur of bar chatter – it all coalesces into an atmosphere you can practically smell. The film doesn't judge its characters; it simply observes them, finding moments of unexpected grace and humor amidst the squalor. Remember the scene where Henry calmly explains his philosophy to the bartender? It’s pure Bukowski, delivered with Rourke’s perfect deadpan rhythm.

Beyond the Bottom Shelf

Barfly wasn't a blockbuster by any means. Made for a modest budget (likely around $3-4 million), it grossed a respectable $8.7 million but certainly didn't set the box office alight like the era's action epics. It found its audience slowly, often discovered, like mine was, tucked away on the video store shelf, a gritty anomaly amongst the colourful VHS boxes. It garnered critical acclaim, particularly at Cannes, but likely bewildered mainstream audiences expecting something more conventional. Yet, its legacy endures. It’s a film that stays with you, forcing a confrontation with uncomfortable truths about art, addiction, and the choices we make. It doesn’t offer easy answers or redemption arcs, mirroring the often-unresolved nature of life itself. Doesn't its unflinching honesty feel almost refreshing compared to more formulaic narratives?

***

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's unwavering commitment to its vision, the truly exceptional and transformative performances by Mickey Rourke and Faye Dunaway, and Barbet Schroeder's masterful creation of atmosphere. It successfully translates the unique spirit of Charles Bukowski's work to the screen, capturing its grime and its strange, defiant beauty without flinching. While its bleakness and deliberate pacing might not be for everyone, its artistic integrity and raw power are undeniable.

Final Thought: Barfly lingers like the taste of cheap whiskey – potent, slightly bitter, but possessed of a truth that’s hard to shake. It’s a film that reminds us that poetry can be found in the most unlikely corners, even amidst the clatter of empty bottles.