Alright, fellow tapeheads, slide that worn-out copy of Smokey and the Bandit Part 3 into the VCR, adjust the tracking if you have to (you probably have to), and let's talk about one of the stranger pit stops in 80s franchise filmmaking. Finding this one on the shelf back in the day always felt... different. Not quite the guaranteed good time of the first two, but there was Jackie Gleason on the cover, promising more Buford T. Justice antics, so you grabbed it anyway, right? This 1983 entry isn't just a sequel; it's practically a fascinating case study in what happens when a sure-fire formula gets put through the Hollywood wringer.

The Return of Justice... Sort Of

The setup feels familiar enough on the surface. Big Enos (Pat McCormick) and Little Enos (Paul Williams, returning with his signature diminutive charm) are bored again and cook up another cross-country challenge. This time, the cargo isn't Coors beer but a giant, likely pungent, stuffed fish destined for the opening of their new seafood restaurant. The catch? They bet Sheriff Buford T. Justice that he can't make the delivery from Miami to Texas in time. Facing retirement and unbearable boredom, Buford accepts, strapping the prize fish to the roof of his increasingly battered patrol car. So far, so... fishy.

But here's where the tape gets tangled. Originally, the film was shot under the title Smokey IS the Bandit, a truly bizarre concept where Jackie Gleason was meant to play both Buford T. Justice and a new version of the Bandit. Yes, you read that right. Test audiences, however, were reportedly baffled (can you blame them?), leading to extensive reshoots. This is where the studio scrambled, realizing they desperately needed some kind of Bandit figure for Buford to chase.

Enter the Snowman, Exit the Star

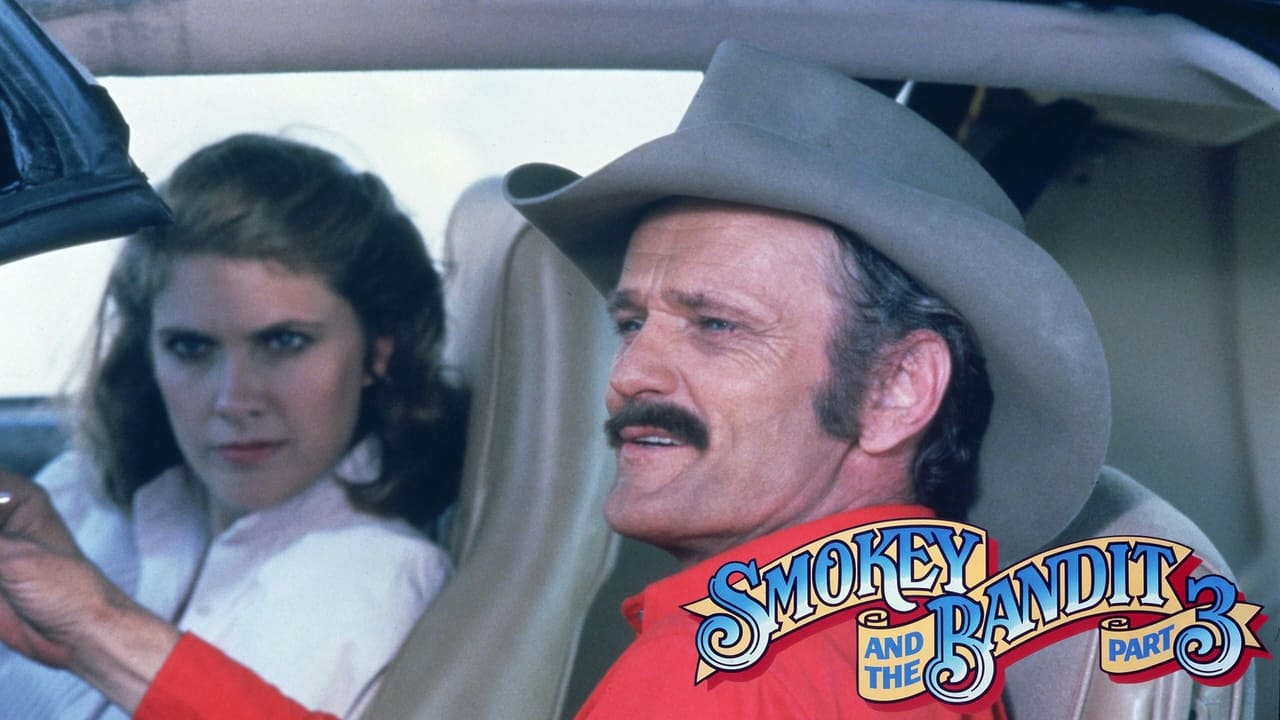

With Burt Reynolds busy being the biggest movie star on the planet (and likely wanting nothing to do with this potential train wreck), the filmmakers turned to the ever-reliable Jerry Reed. Instead of reprising his role as Cledus "Snowman" Snow outright initially, the reshot footage positions Cledus as impersonating the Bandit, complete with a fake mustache and a red shirt, hired by Big Enos to harass Buford along the way. It’s a convoluted fix, and you can almost feel the seams where the original footage meets the new stuff. Reed does his best, flashing that familiar grin and bringing some much-needed charisma, but it feels like a patch job because, well, it was. Reynolds himself does pop up in a blink-and-you'll-miss-it cameo near the end (reportedly cobbled together from unused footage from the second film), a final, almost ghostly reminder of what made the original spark.

Gleason Unleashed (For Better or Worse)

Without the Bandit as a true co-lead for much of the runtime, the film leans heavily on Jackie Gleason. And Gleason, consummate professional that he was (even landing a reported $1 million payday for the dual role initially planned, a huge sum back then!), throws himself into the Buford T. Justice persona with gusto. His repertoire of insults ("sumbitch," "dipstick") is fully deployed, and his slow burns and exasperated reactions remain the film's primary source of comedy. Watching him interact with his perpetually bewildered son Junior (Mike Henry, gamely returning) still provides moments of genuine slapstick fun. However, without the sharp banter and chemistry he shared with Reynolds, Buford's shtick occasionally wears thin, feeling more repetitive than riotous.

Stunts on a Budget

Let's talk action, because even a troubled Bandit sequel had to deliver some vehicular mayhem. Directed by Dick Lowry, a prolific TV movie director who understood efficiency, the stunts feel appropriately gritty for the era. We get the requisite car jumps, near misses, and cop car pile-ups. Remember how real those crashes felt back then? No slick CGI smoothing out the edges – just practical stunt work with actual metal crunching. There’s a certain weight and impact to seeing real cars skid, flip (sometimes unintentionally, according to stunt lore!), and slam into each other that modern blockbusters often lack. One sequence involving Buford driving through a KKK rally provides a bizarre, very 80s comedic set piece that relies entirely on chaotic driving and panicked reactions. While none of the chases reach the iconic status of the first film's bridge jump or the second's desert demolition derby, the commitment to practical effects is still evident and appreciated by us fans of the tangible.

A Franchise Running on Fumes?

Smokey and the Bandit Part 3 landed with a thud back in '83. Critics mostly savaged it, and audiences, likely missing Reynolds and confused by the Bandit shenanigans, stayed away in droves. It grossed a mere $5.6 million domestically, a catastrophic drop from the $126 million haul of the original (Smokey and the Bandit from 1977) and the respectable $66 million of Smokey and the Bandit II (1980). It effectively killed the theatrical franchise (though some later TV movies starring Brian Bloom tried to revive the concept).

Watching it now on VHS (or your format of choice), it’s undeniably the weakest link. The plot is nonsensical, the absence of Reynolds is keenly felt, and the reshoot patchwork is obvious. Yet... there's a strange charm to it. It's a fascinating artifact of studio panic, a showcase for Gleason's comedic endurance, and a reminder of a time when even a troubled sequel featured honest-to-goodness stunt driving. It’s like that weird cassette tape you found in a bargain bin – maybe not a greatest hit, but a curious B-side you listen to occasionally out of pure, unadulterated nostalgia.

VHS Heaven Rating: 3/10

Justification: The score reflects the film's undeniable narrative mess, weak script, and the palpable absence of Burt Reynolds. However, it avoids absolute zero thanks to Jackie Gleason's committed (if repetitive) performance, some genuinely decent practical stunt work indicative of the era, and its undeniable status as a fascinatingly flawed piece of 80s franchise history. Jerry Reed also earns it a point just for showing up and trying his best under weird circumstances.

Final Thought: Smokey and the Bandit Part 3 is the cinematic equivalent of Buford T. Justice's patrol car by the end of the movie – battered, patched-up, barely holding together, but somehow, inexplicably, still moving down the road. For completists and Gleason die-hards only, but a weirdly compelling watch if you know the chaotic story behind the scenes.