It arrives not so much as a film, but as a barely contained explosion in a satirical factory. Watching Lindsay Anderson’s Britannia Hospital today feels akin to discovering a volatile, slightly unstable artifact from another time – specifically, 1982 Britain. It wasn't just another movie on the shelf at the video store; it carried a certain notoriety, a whiff of controversy that made reaching for that particular VHS tape feel like an act of minor rebellion. This wasn't gentle satire; it was a full-frontal assault.

### A Nation Under the Knife

The premise itself is pure, distilled chaos: Britannia Hospital, a venerable institution celebrating its 500th anniversary, is preparing for a visit from HRH The Queen Mother (or a convincing lookalike). Simultaneously, ancillary workers are on strike, picketing ferociously outside; protestors are demonstrating against an African dictator being treated as a VIP patient within; and deep in the bowels of the hospital, the brilliant but utterly mad Professor Millar (Graham Crowden) is preparing to unveil his magnum opus – a project with implications so bizarre they beggar belief. Into this maelstrom wanders Mick Travis (Malcolm McDowell), reprising his iconic character from Anderson's earlier, seminal films If.... (1968) and O Lucky Man! (1973), this time as an undercover reporter trying to make sense of the bedlam.

It’s less a narrative and more a series of increasingly frantic, interconnected vignettes showcasing a nation seemingly tearing itself apart. Anderson, working again with writer David Sherwin, uses the hospital not just as a setting, but as a microcosm of Britain itself – hierarchical, bureaucratic, riddled with class conflict, and teetering on the brink of complete systems failure. The strikes, the protests, the out-of-touch administration desperately trying to maintain appearances – it all felt pointedly relevant in the early Thatcher years, and perhaps resonates with a disconcerting familiarity even now. Doesn't the struggle between entrenched power and disruptive forces feel eternally relevant?

### Controlled Anarchy, On Screen and Off?

Anderson directs with a style that feels both documentary-real and wildly theatrical. The camera often seems to be scrambling to keep up with the unfolding pandemonium, capturing the grit and grime of the picket lines alongside the sterile, almost futuristic weirdness of Millar’s experimental wing. It’s a jarring juxtaposition that keeps the viewer perpetually off-balance. Interestingly, filming reportedly took place at functioning hospitals (including Addenbrooke's in Cambridge and Harefield Hospital, Middlesex), adding another layer of reality bleeding into the absurdist fiction.

The film famously received a hostile reception at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival, reportedly being booed during its screening. Anderson himself was apparently philosophical, quoted as saying something to the effect of "Do you really think we make films for critics at Cannes?" This defiance seems baked into the film's DNA. It refuses to be polite, refusing easy answers or comfortable resolutions. Made for around £3 million, it wasn't a runaway box office success, perhaps proving too abrasive for mainstream tastes even then. Yet, its very refusal to compromise is part of what makes it stick in the mind.

### A Rogues' Gallery of British Talent

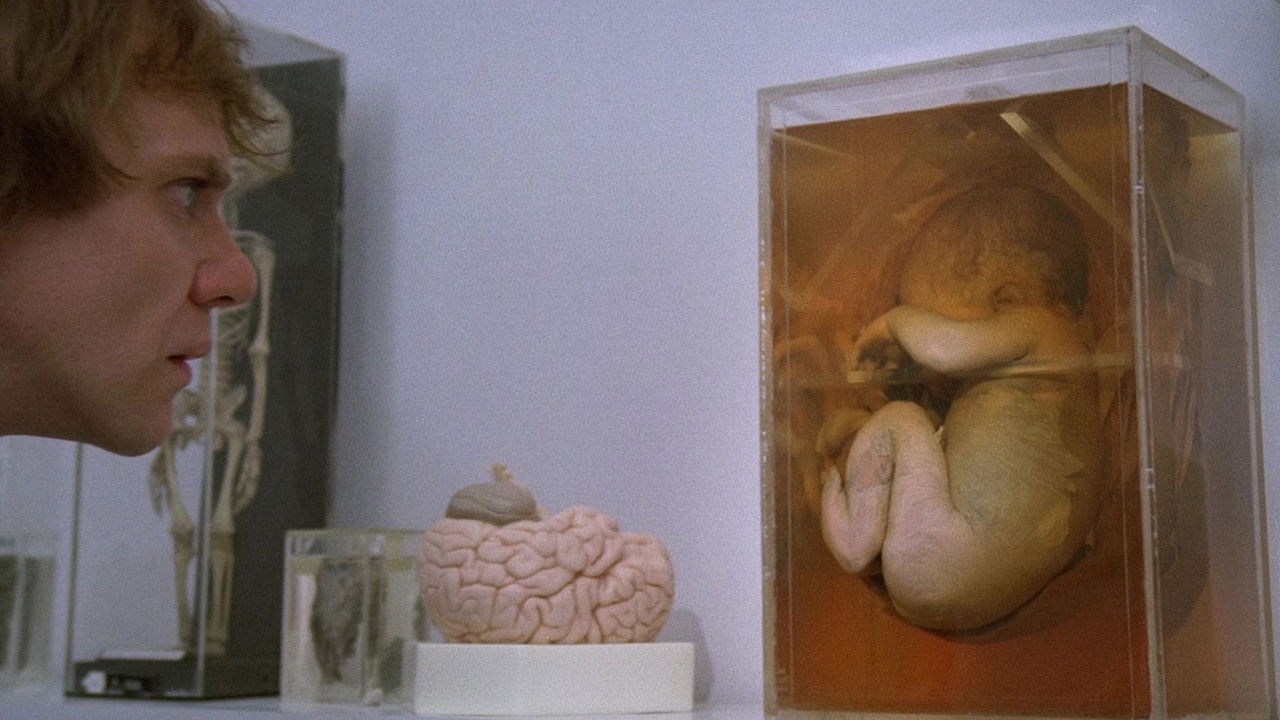

The cast is a veritable who’s who of British character actors, each bringing their distinct energy to the madness. Leonard Rossiter is unforgettable as Vincent Potter, the perpetually flustered hospital administrator trying to juggle unions, royalty, and institutional collapse. His performance is a masterclass in barely suppressed hysteria, a tightrope walk between comedy and tragedy. Graham Crowden as Professor Millar embodies scientific hubris dialed up to eleven, delivering his lines about the future of humanity with a chillingly cheerful conviction. His creation, the film's grotesque centerpiece, remains one of the most audacious and unsettling images in 80s British cinema.

And then there’s Malcolm McDowell. His Mick Travis here is less the wide-eyed innocent of O Lucky Man! and more a weary, cynical observer, armed with hidden cameras. He acts as our fractured guide through the chaos, but even he is ultimately overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the institutional breakdown. It's a different shade of Travis, reflecting perhaps a disillusionment with the ideals explored in the earlier films. Seeing familiar faces like Alan Bates, Arthur Lowe (in one of his final roles), Richard Griffiths, and Mark Hamill (yes, that Mark Hamill, in a small but noticeable part) pop up adds to the slightly surreal, densely populated feel of this doomed institution.

### The Bitter Pill of Satire

Britannia Hospital doesn't pull its punches. Its targets are broad and numerous: the crumbling NHS, militant unions, the sensationalist media, the detached aristocracy, scientific arrogance, even the easily led protestors. Some might argue its approach is too scattershot, its critiques too broad or heavy-handed. The humor is pitch-black, often grotesque, and rarely offers relief. The infamous ending sequence, involving Professor Millar's 'Genesis' project, is a moment of such bizarre, body-horror-inflected allegory that it likely sealed the film's fate for many viewers back in the day. It’s designed to provoke, to disturb, and it absolutely succeeds.

Watching it now, on a format far removed from the worn-out rental VHS tape I first encountered it on, the film feels like a furious time capsule. It captures a specific moment of national anxiety and fractures it through a lens of extreme satire. It asks uncomfortable questions about progress, humanity, and the very fabric of society. What happens when all the systems we rely on begin to fail simultaneously? What monstrosities might be born from our desperation for order and control?

Rating: 7/10

Justification: Britannia Hospital is far from perfect. It's messy, often abrasive, and its narrative can feel disjointed. However, its sheer audacity, its ferocious satirical energy, and the committed performances (especially from Rossiter and Crowden) make it a compelling, if uncomfortable, watch. It earns points for its uncompromising vision and its status as a unique, controversial piece of British cinema history, even if its reach sometimes exceeds its grasp. It perfectly embodies that feeling of discovering something truly strange and challenging in the aisles of the video store.

Final Thought: A barbed, chaotic, and ultimately unforgettable diagnosis of a nation's ailments, Britannia Hospital remains a potent, if bitter, prescription from a fiercely individual filmmaker. It lingers not as a comforting memory, but as a persistent, nagging question mark about where we were headed then, and perhaps, where we find ourselves now.