Okay, settle in, fellow tapeheads. Let's rewind to a film that doesn't blast onto the screen with explosions or synth-pop, but rather arrives with the quiet, searing intensity of the African sun it depicts. I'm talking about Bruce Beresford's 1980 masterpiece, Breaker Morant. Pulling this one off the shelf at the local video store always felt a bit different, didn't it? The cover art promised military history, maybe some adventure, but what awaited inside was something far more profound – a courtroom drama that grapples with the brutal ambiguities of war, empire, and justice, leaving questions that echo long after the VCR clicks off.

### The Heat of the Veldt, The Chill of the Courtroom

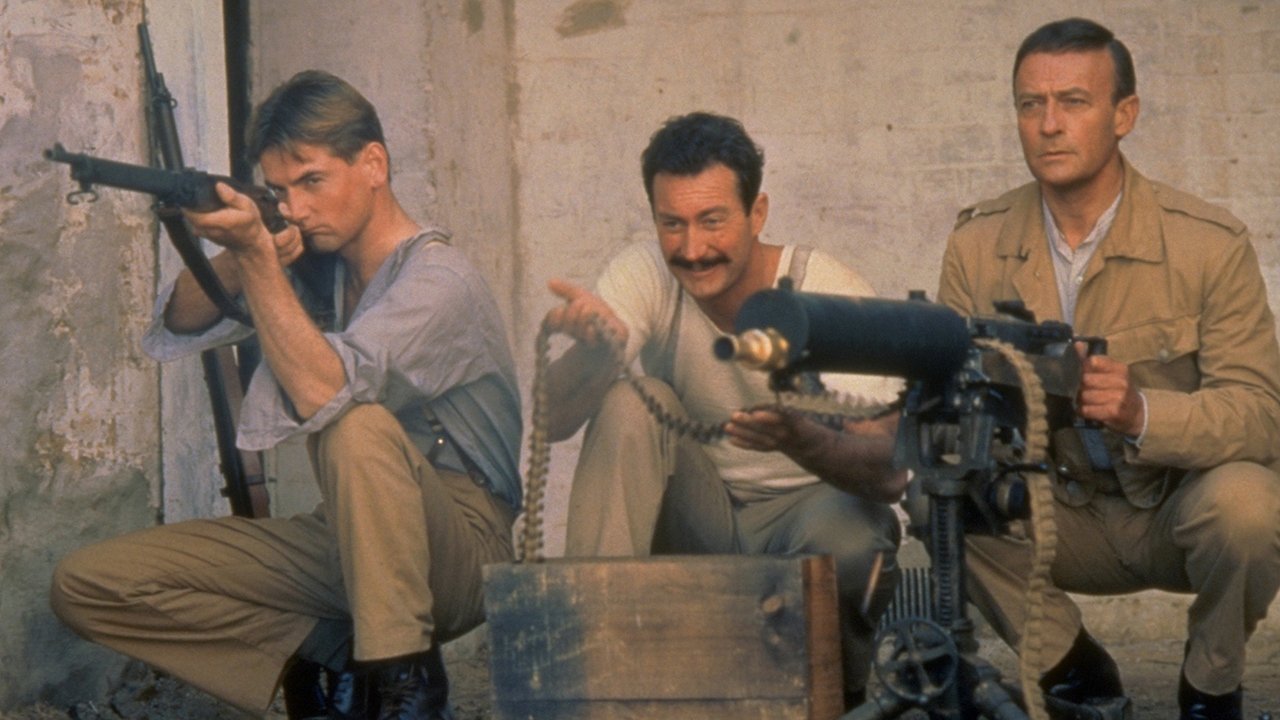

The film transports us to South Africa during the Boer War, around the turn of the 20th century. We're thrown immediately into the thick of it: three Australian officers serving with the British forces – Lieutenants Harry "Breaker" Morant (Edward Woodward), Peter Handcock (Bryan Brown, in an early notable role), and George Witton (Lewis Fitz-Gerald) – are on trial for executing Boer prisoners and a German missionary. From the outset, the atmosphere is thick with tension. Beresford, who would later helm the very different Driving Miss Daisy, masterfully contrasts the expansive, sun-baked landscapes of the South African veldt (convincingly recreated in South Australia, believe it or not) with the claustrophobic confines of the military courtroom. You can almost feel the dust and the simmering resentment.

The central narrative unfolds through the trial, punctuated by flashbacks that reveal the events leading to the charges. It’s a structure that keeps the viewer constantly questioning: Were these men simply following ambiguous orders in a brutal guerrilla war, or did they commit cold-blooded murder? Were they patriots, scapegoats, or something unsettlingly in between?

### More Than Just Soldiers

What truly elevates Breaker Morant is the powerhouse trio of performances at its core. Edward Woodward, perhaps better known to some later for his stoic turn in TV's The Equalizer, is simply magnetic as Harry Morant. He imbues the character with a complex mix of charm, world-weariness, artistic sensibility (Morant was a published poet, a fact the film subtly incorporates), and a chilling capacity for ruthlessness. Woodward doesn't shy away from the character's darker shades, making his portrayal utterly compelling. You understand his men's loyalty, even as you grapple with his actions.

Equally brilliant is Jack Thompson as Major J.F. Thomas, the inexperienced solicitor assigned the near-impossible task of defending the accused. Thompson radiates righteous fury and dogged determination. His passionate closing argument remains one of cinema's great courtroom moments, a blistering indictment not just of the specific charges, but of the political machinations driving the trial. You feel his frustration, his dawning horror at the system he represents. John Waters provides quiet dignity as Captain Alfred Taylor, another officer caught in the web, his stoicism a counterpoint to Morant's volatility.

### A Question of Orders

The film masterfully explores the murky territory of military command and responsibility. The defense hinges on the claim that unwritten orders – or at least tacit approval from higher up, including the legendary Lord Kitchener – sanctioned the execution of prisoners. Was it a necessary tactic in a savage conflict, or a convenient excuse? This resonates deeply, forcing us to consider how easily lines blur in wartime, and how readily political expediency can override justice.

It’s fascinating to learn that the film itself was adapted by Beresford, Jonathan Hardy, and David Stevens from a 1978 play by Kenneth G. Ross. This theatrical origin likely contributes to the power of its dialogue and the intensity of the courtroom scenes. Reportedly made for a modest budget (under A$1 million), its impact far outweighed its cost, earning critical acclaim worldwide, including a Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar nomination and accolades at Cannes. It became a cornerstone of the Australian New Wave, proving Australian cinema could tackle complex historical and moral themes with universal resonance.

While based on real events and figures, the film presents a specific viewpoint, and historical debates about the actual guilt or innocence of Morant and his men continue to this day. Breaker Morant doesn't necessarily offer easy answers, but rather forces the viewer into the heart of the dilemma. It portrays the accused as flawed men caught in the gears of empire, potentially sacrificed to appease German political pressure following the missionary's death and to pave the way for peace talks.

### Legacy Under a Foreign Flag

Breaker Morant isn't always an easy watch. It's deliberate, dialogue-heavy, and deals with grim subject matter. Yet, its power is undeniable. It speaks volumes about the nature of war, the complexities of colonialism, and the often-brutal realities hidden behind patriotic fervor. It asks uncomfortable questions about accountability – who truly bears responsibility when atrocities are committed under the banner of duty? Doesn't the very nature of irregular warfare, which feels chillingly familiar even today, push soldiers towards impossible choices?

The film's critique of British imperial attitudes and the use of colonial troops as potentially expendable assets is sharp and lingers long after viewing. It’s a stark reminder that the dynamics of power and politics often dictate the course of justice, especially during wartime.

Rating: 9/10

Justification: Breaker Morant earns this high score through its exceptional performances, particularly from Woodward and Thompson, its intelligent and gripping screenplay, Beresford's assured direction, and its unflinching examination of complex moral and historical themes. It's a masterclass in courtroom drama and war storytelling that avoids easy heroism or villainy. While its pacing might feel measured to some modern viewers, its intellectual and emotional depth is undeniable. It stands as a landmark of Australian cinema and a powerful, thought-provoking film that remains relevant.

Final Thought: This is one of those VHS tapes that, once watched, wasn't easily forgotten. It doesn't offer the escapism of many 80s classics, but instead provides something far more valuable: a searing, intelligent exploration of the shadows cast by war and empire, leaving you to ponder where duty ends and murder begins. A true classic that demands attention.