What weight does a shadow carry? Can an illusion hold together an empire, even when the substance is gone? These aren't idle thoughts after watching Akira Kurosawa's sprawling 1980 epic, Kagemusha (meaning "Shadow Warrior"). No, this is a film that burrows under your skin, lodging itself deep with its questions about identity, power, and the often-tragic space between the man and the myth. Renting this back in the day, likely on two hefty VHS tapes, felt like an event – a commitment to something far removed from the usual action fare, something demanding patience but promising immense reward.

A Thief Becomes a Lord

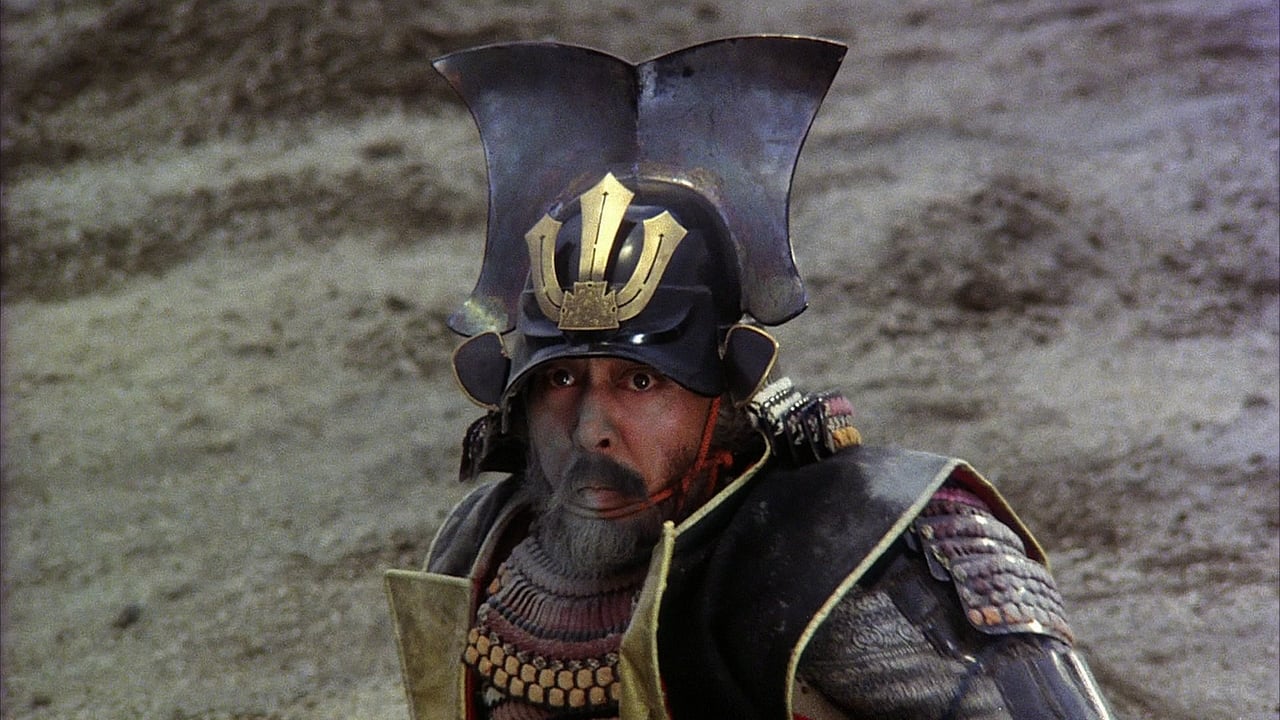

The premise is deceptively simple, yet rich with dramatic potential. In 16th Century Japan, during the turbulent Sengoku period, the powerful warlord Takeda Shingen (Tatsuya Nakadai) is mortally wounded. To prevent chaos and keep rival clans at bay, his generals employ a desperate measure: they find a petty thief, also played by Nakadai, who bears an uncanny resemblance to the dying lord. This thief, initially coarse and self-serving, is trained to become Shingen's double – his kagemusha. He must fool everyone, from Shingen's inner circle and loyal retainers (Tsutomu Yamazaki shines as Shingen's brother Nobukado) to his concubines and even his beloved grandson. The fate of the Takeda clan rests on this fragile deception.

The Master Returns

Watching Kagemusha today, it’s staggering to remember this was Akira Kurosawa’s grand return after nearly a decade of struggling to finance his projects following the commercial failure of Dodes'ka-den (1970). It’s a story familiar to cinephiles: the project stalled until two ardent admirers, George Lucas (fresh off Star Wars) and Francis Ford Coppola (riding high from Apocalypse Now), stepped in as international executive producers. Their clout secured the final funding from 20th Century Fox, allowing Kurosawa to realize his vision. And what a vision it is. Kurosawa, ever the painterly filmmaker, composed the film with meticulous care – his own stunningly detailed paintings served as storyboards, essential tools not just for planning but for convincing backers of the film's potential grandeur. The film’s look, captured by cinematographers like Takao Saito and Masaharu Ueda, is unforgettable: vast landscapes dwarf human figures, compositions are balanced with artistic precision, and the deliberate use of color, especially the recurring motif of vibrant red against muted earth tones, carries potent symbolic weight.

A Performance of Duality

At the heart of it all is Tatsuya Nakadai. His dual performance is nothing short of extraordinary. It's not just about looking alike; it's about capturing the absence of Shingen within the Kagemusha's posture, the gradual assumption of a dignity that isn't truly his, the flickers of the thief's fear and cunning beneath the carefully constructed facade. There's a profound sadness in watching this man become subsumed by a role he can never truly own. It’s fascinating trivia that Nakadai wasn't the first choice. The legendary Shintaro Katsu, famed for his iconic Zatoichi role, was initially cast but was either fired or quit after reportedly clashing with Kurosawa's notoriously autocratic directing style on the very first day of shooting. While one wonders what Katsu might have brought, Nakadai's interpretation feels definitive – controlled, nuanced, and deeply human.

Echoes of Battle, Whispers of Change

While Kagemusha features battles, Kurosawa often presents them with a sense of distance or focuses on the aftermath rather than graphic, close-up violence. The legendary Battle of Nagashino, a turning point signifying the decline of traditional samurai tactics against firearms, is depicted with haunting power – less through chaotic clashes and more through stillness, reaction shots, and the symbolic imagery of riderless horses galloping through smoke and carnage. This wasn't just historical recreation; it felt like an elegy for a dying way of life. The sheer scale is immense – thousands of extras, meticulously crafted armor and banners, vast locations across Japan – all achieved on a budget that, while substantial for Japan at the time (around ¥2.4 billion, roughly $6 million USD back then, perhaps $22 million today), feels astonishingly efficient given the on-screen results.

The Weight of the Shadow

Ultimately, Kagemusha probes the nature of leadership and legacy. Is the symbol enough? Can the idea of Shingen hold the clan together? The film suggests that while the shadow can offer temporary refuge, it lacks the substance, the decisive will, of the genuine article. The Kagemusha finds himself trapped, respected only for the man he impersonates, powerless to prevent the tragic trajectory set in motion by Shingen's ambitious but reckless son, Katsuyori (Kenichi Hagiwara). The famous dream sequence, a surreal swirl of color and Noh-inspired imagery, visualizes the Kagemusha's internal struggle and the overwhelming weight of the dead lord's presence.

This is a film that rewards contemplation. It doesn't offer easy answers but instead leaves you pondering the masks we all wear, the roles we play, and the often-unbridgeable gap between perception and reality. Winning the Palme d'Or at Cannes in 1980 (shared with All That Jazz) cemented its status as a masterpiece and paved the way for Kurosawa’s equally ambitious Ran (1985). Unearthing this from the depths of the video store often meant finding the longer Japanese cut or the slightly trimmed international version – either way, it was an immersive dive into cinematic history.

Rating: 9/10

Kagemusha is a towering achievement. Its deliberate pace might test some viewers accustomed to modern editing, but its visual splendor, thematic depth, and Nakadai's central performance are undeniable. It's a powerful, moving epic that uses the specific canvas of feudal Japan to ask universal questions. More than just a historical drama, it’s a profound meditation on what it means to be, and to seem. What lingers most isn't just the spectacle, but the haunting image of a man lost within the reflection of greatness.