Alright, fellow tapeheads, settle in. Dim the lights, maybe crack open a Tab if you can find one, because tonight we're diving headfirst into a swirling vortex of cosmic cheese, laser beams, and questionable fashion choices. I’m talking about the one, the only, Starcrash (1978) – a film that practically screams "We saw Star Wars and had some spare lire lying around!"

Remember pulling this box off the shelf at Blockbuster or maybe your local mom-and-pop video store? The cover art alone promised intergalactic adventure on a scale that the actual film… well, let's just say it tried valiantly. Directed by Italian filmmaker Luigi Cozzi (who later gave us the wonderfully schlocky Hercules starring Lou Ferrigno in 1983), Starcrash is less a coherent space opera and more a gloriously messy, utterly charming fireworks display of pure B-movie ambition. It hit screens just after George Lucas changed the game, arriving perhaps a touch late to the party but crashing through the door with unforgettable, Day-Glo enthusiasm.

### A Galaxy Far, Far Away... Sort Of

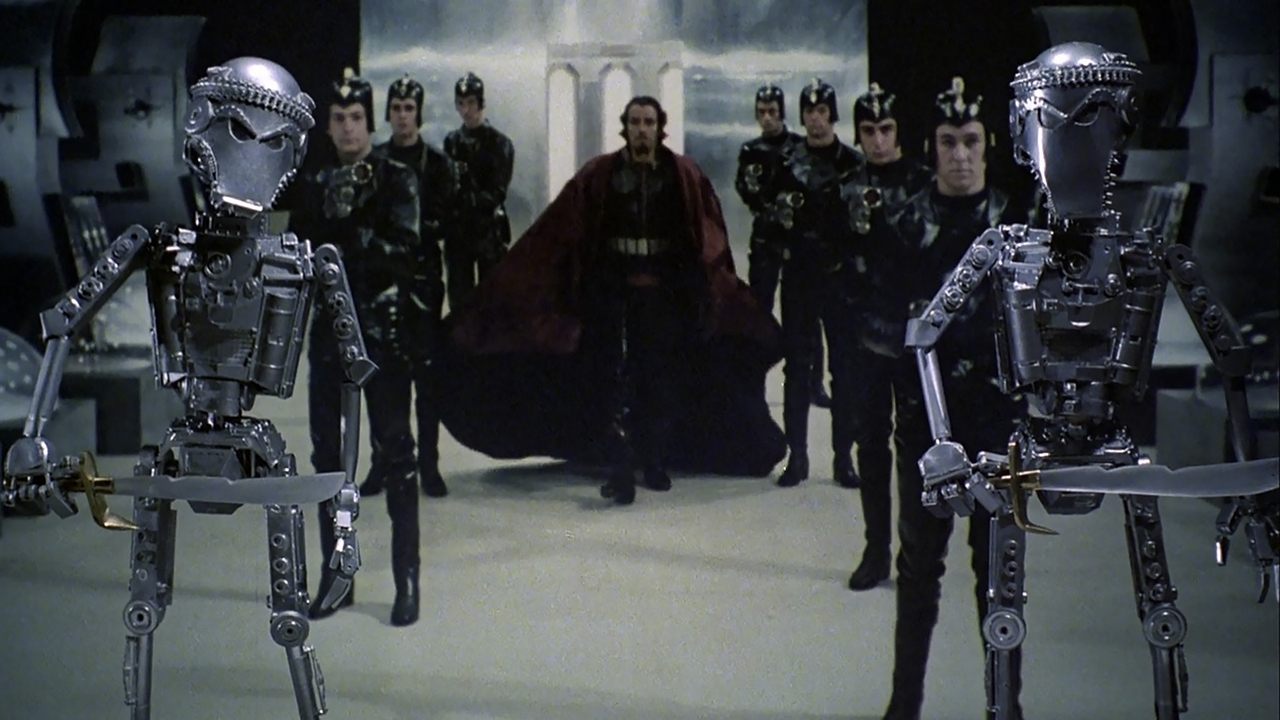

The plot, such as it is, involves the outlaw smugglers Stella Star (Caroline Munro, radiating pure space-babe energy) and her sidekick Akton (Marjoe Gortner, the former child evangelist turned actor), who get roped into a mission for the Emperor of the Galaxy. And who plays the Emperor? None other than the legendary Christopher Plummer, lending an almost comical level of gravitas to lines about "imperial battleships" and "the haunted stars." Rumour has it Plummer took the gig partly for a paid trip to Rome, where much of the film was shot at the famed Cinecittà Studios – a classic example of practical decision-making meeting intergalactic fantasy. Their mission: find the Emperor's missing son and stop the vaguely evil Count Zarth Arn (an appropriately sneering Joe Spinell) from unleashing his ultimate weapon. Along the way, they team up with a fussy robot cop named Elle (think C-3PO’s less competent cousin voiced with a bizarre Southern drawl in the English dub) and the missing Prince Simon, played by a very young, very earnest David Hasselhoff.

### Feel the Practicality!

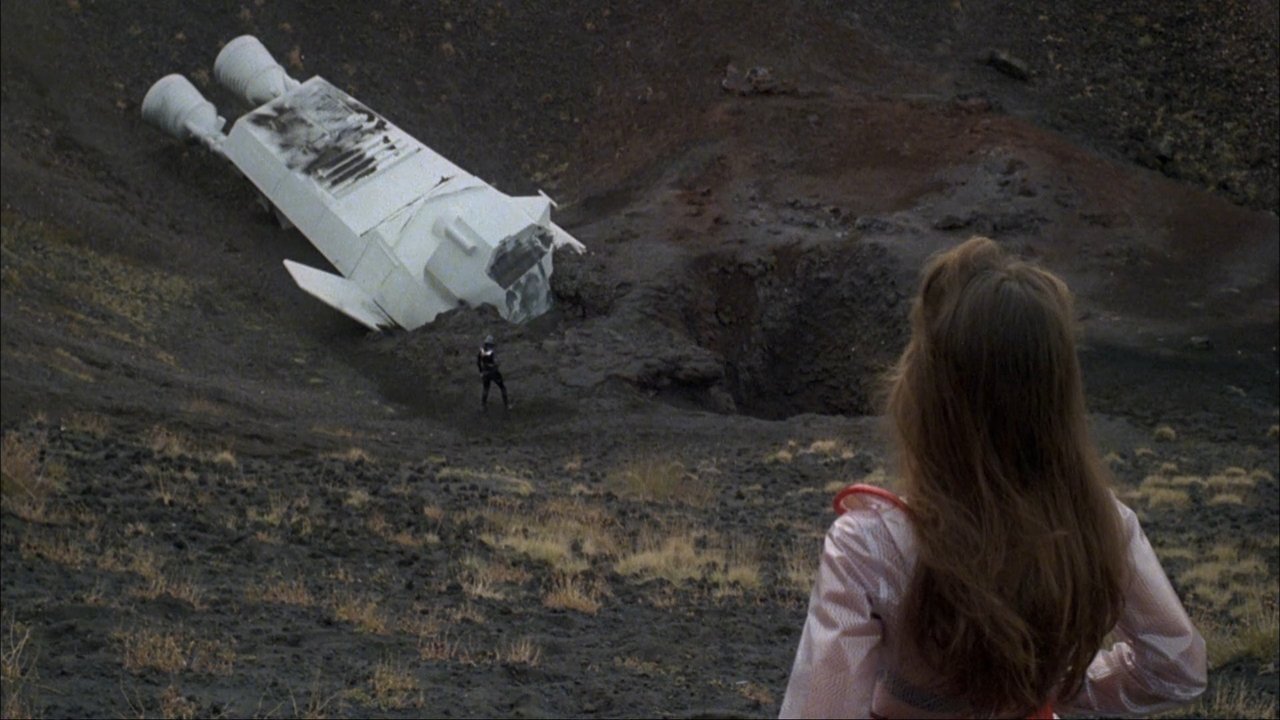

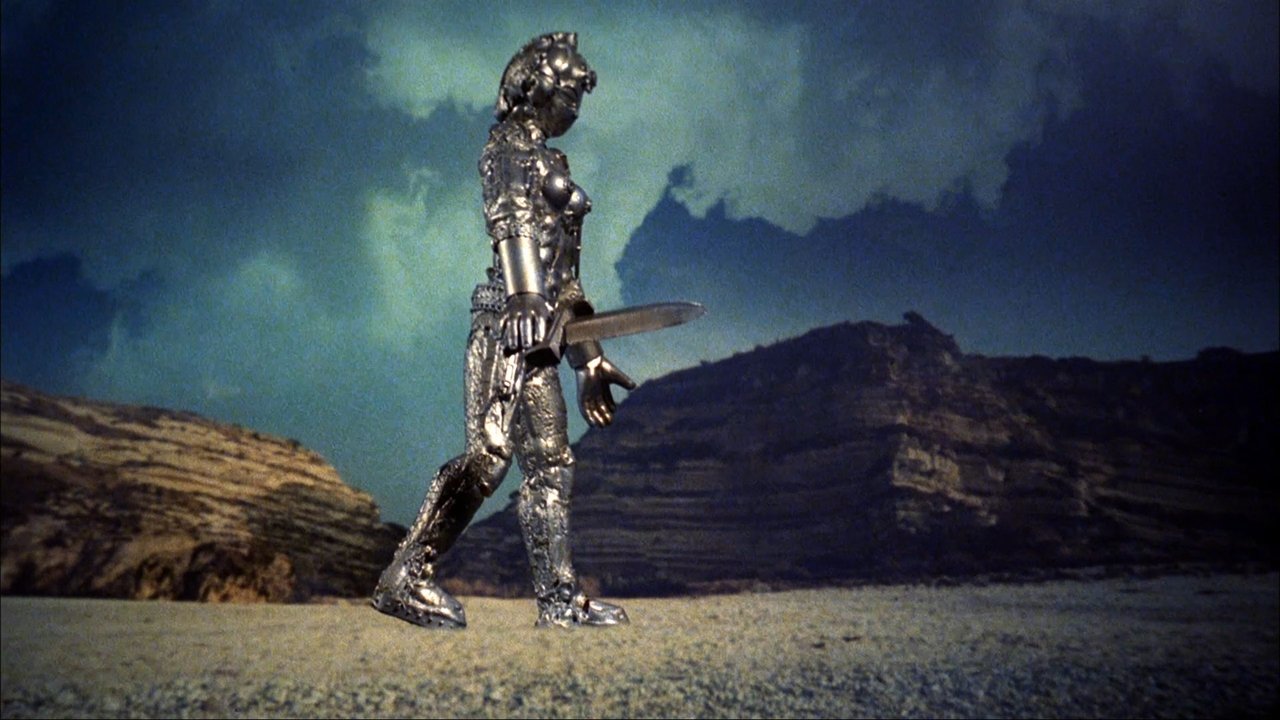

Let's talk about what makes Starcrash a true VHS Heaven artifact: the effects! Forget slick CGI – this is the realm of miniatures on visible wires, stop-motion monstrosities, and gloriously unsubtle pyrotechnics. Cozzi, working with a budget that wouldn't cover the catering on a modern blockbuster (reportedly around $4 million, peanuts even then for sci-fi), threw everything at the screen. Remember those spaceship battles? Models jerking across starfields, lasers looking suspiciously like animation drawn directly onto the film cells, and explosions that felt wonderfully physical.

There's a charming, handmade quality to it all. The stop-motion sequences, like the bronze amazons Stella battles on one planet, have that jerky, dreamlike movement that feels ancient now but was genuinely painstaking work back then. Was it seamless? Heavens, no. But it had texture. You could almost feel the passion (and perhaps desperation) of the effects team, led by folks like Armando Valcauda, trying to conjure cosmic wonders out of plastic, paint, and sheer willpower. Compare that to today’s often weightless digital creations – there’s a strange satisfaction in seeing something actually blow up, even if it’s clearly a foot-long model packed with firecrackers.

### Style Over Substance (and What Style!)

Beyond the effects, Starcrash is a visual feast of questionable taste. Caroline Munro, a veteran of Hammer Horror and The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), spends most of the film in variations of a space bikini that leaves little to the imagination – iconic, perhaps, but hardly practical for smuggling or combat. Cozzi clearly knew his star's appeal. Marjoe Gortner’s Akton is equally baffling, a mystical character with vague Force-like powers and a weapon that looks suspiciously like a lightsaber someone built in their garage. He smiles beatifically through most of the chaos, adding to the film’s surreal charm.

The production design is a riot of colour, clashing aesthetics, and sets that sometimes look like they might fall over if someone sneezes too hard. It’s pure pulp sci-fi visualized with the flair of an Italian B-movie maestro. And the score! Incredibly, the soaring, occasionally bombastic music is by John Barry, the legendary composer behind countless James Bond themes. Apparently, Barry owed producer Nat Wachsberger a favour, leading to one of the most incongruously classy soundtracks ever attached to such a cheerfully goofy film.

### Cult Classic Credentials

Critically savaged upon release, Starcrash quickly faded from theatres but found a second life on home video and late-night TV. This is where films like Starcrash truly thrived – discovered by kids staying up past their bedtime or adventurous renters looking for anything with spaceships on the cover. It became a cult classic precisely because of its flaws: the nonsensical plot, the often wooden dialogue (especially in the English dub), the visible seams in its special effects. It’s earnest in its silliness, ambitious beyond its means, and ultimately, just plain fun in a way few films dare to be anymore. Did Roger Corman’s New World Pictures, known for spotting B-movie gold, help distribute it in the US? You bet they did. They knew an audience existed for this brand of enthusiastic spectacle.

Rating: 5/10

Let's be honest, on a technical or narrative level, Starcrash is a mess. The plot holes are large enough to fly an Imperial battleship through, the acting ranges from Shakespearean slumming (Plummer) to bewildered (Gortner) to enthusiastically camp (Munro), and the effects often induce chuckles rather than awe. However, for sheer gonzo entertainment value, nostalgic charm, and as a time capsule of post-Star Wars B-movie opportunism, it’s weirdly irresistible. This rating reflects its technical shortcomings balanced against its undeniable cult appeal and rewatchability if you're in the right frame of mind.

Final Take: Starcrash is the cinematic equivalent of finding a dusty, brightly coloured plastic toy in the attic – slightly broken, maybe missing a few pieces, but capable of sparking disproportionate amounts of joy. It’s a reminder of a time when passion and practical effects, however flawed, could still try to reach for the stars, even if they only made it halfway. Fire up the VCR in your mind; this one’s a glorious, fuzzy memory worth revisiting.