That final, guttural scream. Even now, decades after first witnessing it flicker across a CRT screen, the image of Donald Sutherland's face contorted in accusation and despair remains seared into the mind. It’s not just a jump scare; it’s the horrifying culmination of relentless, creeping dread, the definitive sound of paranoia made manifest. Philip Kaufman's 1978 reimagining of Invasion of the Body Snatchers isn't merely a remake; it's a distinct mutation, a chillingly effective translation of 50s anxieties into the cynical, disillusioned landscape of the late 1970s. Forget the Red Scare subtext of the original – this is about urban alienation, the breakdown of trust, and the terrifying possibility that the person sleeping next to you is no longer them.

The Slow Creep of the Pods

Kaufman wastes no time establishing an unsettling atmosphere. From the eerie, otherworldly beauty of the spores drifting from a dying planet to Earth, landing unseen on rain-slicked San Francisco leaves, there's an immediate sense of invasive wrongness. The film masterfully builds its tension not through frantic action, but through subtle shifts in behavior. A husband suddenly cold and distant, a friend’s vacant stare, the unsettling normalcy of garbage trucks hauling away disturbing, fibrous husks in the dead of night. It taps into that primal fear of the familiar turning alien, the uncanny valley stretched to its breaking point.

The story follows Matthew Bennell (Donald Sutherland), a health inspector whose initial skepticism about his colleague Elizabeth Driscoll's (Brooke Adams) fears that her boyfriend has been replaced slowly crumbles as the evidence mounts. They find themselves increasingly isolated, unsure who to trust in a city that seems to be falling asleep, only to wake up... different. The brilliance lies in how grounded it feels initially. These aren't B-movie hysterics; they are ordinary people grappling with an impossible, terrifying reality.

Sounds of Silence, Sights of Horror

Much of the film's power lies in its technical execution. Denny Zeitlin's score is a masterpiece of unsettling electronic textures and discordant strings, often punctuated by unnerving silences or the chillingly organic sounds associated with the pods. Sound designer Ben Burtt (yes, the legendary sound wizard behind Star Wars) contributes significantly, particularly with the horrifying pod-person scream – a sound reportedly achieved by manipulating pig squeals – that acts as an alarm system for the duplicates. It’s a sound that drills directly into your nervous system.

And the practical effects? For 1978, they remain astonishingly effective and deeply disturbing. The birth of the duplicates from the pulsating pods, the slimy tendrils reaching out, culminating in those half-formed, horrifyingly blank copies – it’s visceral stuff. That infamous scene with the dog… you know the one. Apparently, that horrifying human-faced dog wasn't even in W.D. Richter's original script; Kaufman added it during production, aiming for something truly jarring and unforgettable. Mission accomplished, wouldn't you agree? It’s a fleeting moment, but it perfectly encapsulates the film's body-horror dread.

A Cast Adrift in Paranoia

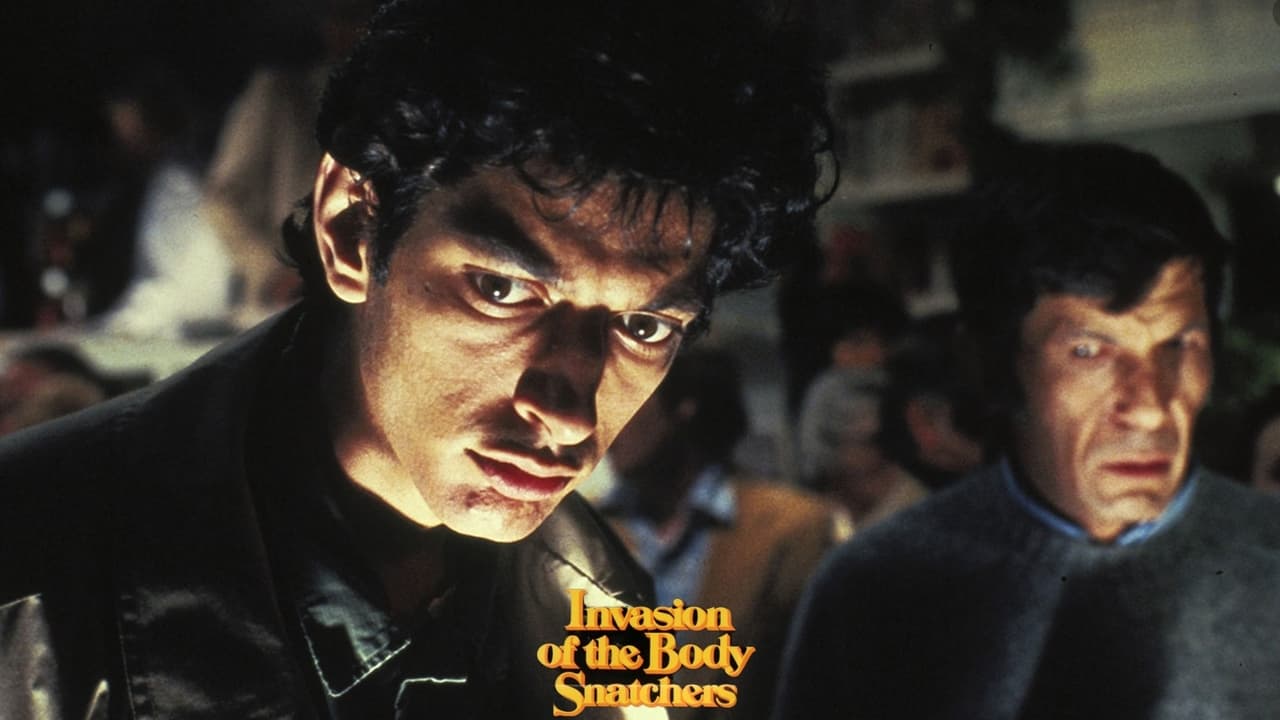

The performances are uniformly excellent. Donald Sutherland is pitch-perfect as Matthew, his journey from wry detachment to frantic desperation utterly convincing. His weariness feels authentic, making his eventual panic all the more affecting. Brooke Adams provides the film's emotional core, her initial fear grounding the fantastical premise. Then there's Leonard Nimoy, stepping away from Spock to play the initially reassuring, ultimately unnerving pop psychologist Dr. David Kibner. It was fascinating casting against type, using Nimoy’s inherent logical calmness to mask something deeply sinister. His calm pronouncements about adapting become terrifyingly ambiguous as the film progresses. And keep an eye out for a fantastic cameo from Kevin McCarthy, star of the 1956 original, reprising his frantic warning – a brilliant, chilling nod to the film's lineage.

Filming in San Francisco wasn't just about capturing iconic landmarks; Kaufman utilized the city's specific geography – its hills, its fog, its pockets of urban anonymity – to enhance the sense of isolation and entrapment. The characters are constantly moving, searching for safety, but the city itself feels like it's closing in. Watching this on VHS back in the day, maybe with the tracking slightly off, only seemed to heighten that feeling of a world subtly, terrifyingly glitching.

Enduring Dread

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) is more than just a great sci-fi horror film; it's a masterclass in sustained paranoia. It expertly preys on anxieties about conformity, loss of identity, and the unsettling feeling that maybe, just maybe, you’re the only one left who sees the truth. Its influence can be felt in countless thrillers and horror films that followed, particularly those dealing with societal breakdown and hidden threats. It proved that remakes could not only honor the original but also carve out their own distinct and terrifying identity.

Does it still hold up? Absolutely. The themes remain potent, the direction is sharp, the performances are committed, and those practical effects still possess a uniquely disturbing quality that CGI often struggles to replicate. It’s a film that crawls under your skin and stays there long after the credits roll, leaving you glancing sideways at your neighbours, just in case.

Rating: 9.5/10

Justification: This near-perfect score reflects the film's masterful direction, chilling atmosphere, superb performances, groundbreaking (and still disturbing) practical effects, and its intelligent adaptation of the source material into a contemporary paranoid thriller. The slow-burn tension, culminating in that unforgettable ending, makes it a high-water mark for the genre. It loses half a point only because absolute perfection is near-impossible, but it comes incredibly close.

Final Thought: Decades later, that final scream echoing through the empty city streets remains one of the most potent and terrifying endings in cinema history – a perfect capsule of 70s disillusionment served cold. Don't fall asleep.