## Snow, Gold, and the Weight of a Secret

There's a coldness that permeates The Claim (2000), and it’s not just the biting wind whipping through the snowbound Sierra Nevada town aptly named Kingdom Come. It settles deep in the bones, much like the guilt carried by Daniel Dillon, the town's de facto ruler. Here is a man who literally struck gold, carving a kingdom from ice and rock, yet his foundation is built not on ore, but on a desperate, unforgivable act committed twenty years prior. Watching it again, perhaps on a DVD rather than a worn VHS tape (it arrived just as the new millennium dawned, a cusp film in many ways), the film feels like a forgotten dispatch from an era grappling with the darker side of ambition, a revisionist Western cloaked in Hardyesque tragedy.

Kingdom Come's Bitter Harvest

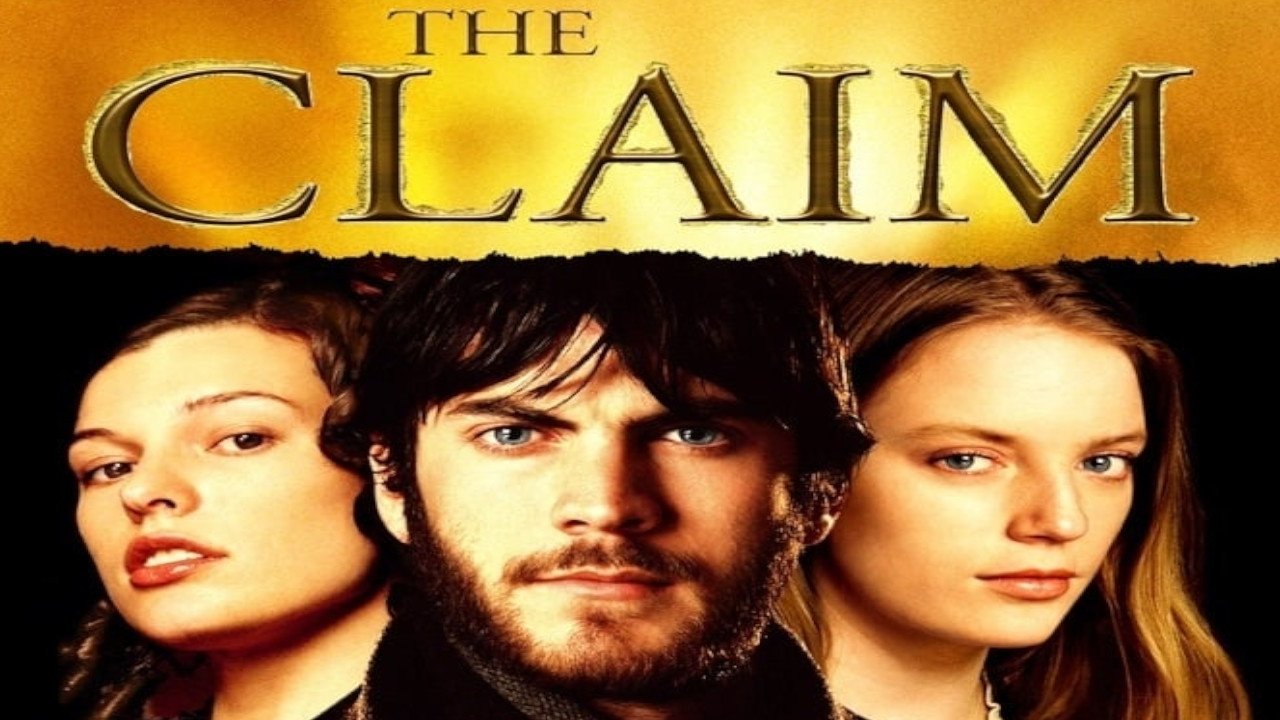

Directed by the ever-versatile Michael Winterbottom (known for everything from 24 Hour Party People (2002) to the Trip series), and penned by Frank Cottrell Boyce adapting Thomas Hardy's The Mayor of Casterbridge, The Claim transports the novel's themes of past sins and inescapable fate from Wessex fields to the unforgiving American frontier of 1867. Dillon (Peter Mullan) owns everything in Kingdom Come – the bank, the saloon, the general store, even the affections of the enigmatic saloon singer Lucia (Milla Jovovich). His word is law, his fortune seemingly boundless. But the arrival of two figures threatens to shatter his carefully constructed empire: Dalglish (Wes Bentley), a surveyor for the Central Pacific Railroad deciding whether to route the tracks through Kingdom Come, bringing prosperity or ruin; and, more devastatingly, Elena (Nastassja Kinski) and her daughter Hope (Sarah Polley), the wife and child Dillon sold for mining rights two decades earlier.

A Towering Central Performance

At the heart of the film's bleak power is Peter Mullan. His Dillon isn't a swaggering Western archetype; he's a man visibly burdened, his face a roadmap of regret etched deeper by the harsh mountain light. Mullan embodies the simmering tension between Dillon's outward authority and his internal decay. You see the desperate calculations behind his eyes as his past arrives like an avalanche, the fierce, almost primal love he develops for the daughter he doesn't initially know is his, and the tragic inevitability of his downfall. It’s a performance of immense gravity, capturing a man who achieved the American dream through an act that fundamentally damned him.

Echoes in the Ensemble

The supporting cast orbits Mullan’s gravitational pull effectively. Milla Jovovich, often known for action roles like The Fifth Element (1997), delivers a nuanced performance as Lucia, a woman caught between her affection for Dillon and her own survival instincts. Her relationship with Dillon feels weary but genuine, complicated by his secrets and the changing landscape. Wes Bentley, fresh off American Beauty (1999), portrays Dalglish with a quiet intensity, representing the relentless march of progress and a different kind of ambition – calculated, modern, and ultimately just as potentially destructive. And Nastassja Kinski brings a haunting fragility to Elena, the ghost of Dillon’s past made flesh, her presence triggering the story’s inexorable slide towards tragedy.

Forged in the Cold

One cannot discuss The Claim without acknowledging its incredible sense of place. The film was notoriously shot under extreme conditions in the Canadian Rockies (near Fortress Mountain, Alberta), with the entire town of Kingdom Come built from scratch on location. You feel the cold, the isolation, the sheer effort of survival in every frame. This wasn't movie magic conjured on a backlot; Winterbottom and cinematographer Alwin H. Küchler capture the tangible struggle against the elements, mirroring the internal struggles of the characters. Knowing the production battled temperatures dropping to -40°C and faced monumental logistical challenges only deepens the appreciation for the film's visceral atmosphere. This commitment to realism, a hallmark often appreciated by fans of gritty 70s and 80s cinema, gives the film a weight few modern CGI-enhanced dramas possess. Even Michael Nyman's score feels less like soaring Western strings and more like a stark, percussive heartbeat against the vast, indifferent landscape.

A Tale Twice Told

Interestingly, the film's adaptation from Hardy is remarkably faithful in spirit, transposing the core moral dilemma and its consequences seamlessly to this new setting. Knowing its literary roots adds another layer – it’s not just a Western, but a timeless story about how our past actions define our present, regardless of the frontier. The original working title, Kingdom Come, perhaps speaks more directly to the ephemeral nature of Dillon’s empire. Despite its ambition and artistry, the film struggled commercially, grossing just over $1 million worldwide against a reported $20 million Canadian dollar budget. It became something of a hidden gem, perhaps too bleak or deliberately paced for mainstream audiences at the time, but one that resonates with those who appreciate character-driven drama and atmospheric storytelling.

Final Thoughts

The Claim isn't an easy watch. It offers few moments of levity and marches towards its tragic conclusion with grim determination. Yet, there's a profound beauty in its bleakness, anchored by Mullan's towering performance and the palpable sense of a specific, harsh time and place. It forces us to consider the true cost of ambition and whether absolution is ever truly possible when the foundations of success are built on profound moral compromise. What lingers most isn't the gold, but the cold, hard weight of choices made and the ghosts they inevitably summon.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's exceptional central performance, its powerful atmosphere born from challenging practical filmmaking, and its thoughtful engagement with complex themes. While its deliberate pacing and bleak outlook might not suit all tastes, its artistry and emotional depth make it a compelling, if melancholic, piece of cinema that deserves rediscovery. It’s a stark reminder that some claims stake themselves not on land, but deep within the human soul.