There's a certain kind of melancholy that hangs heavy over some films, a weight that feels deeper than just the narrative unfolding on screen. Watching Billy Bob Thornton's adaptation of Cormac McCarthy's All the Pretty Horses (2000) today evokes exactly that feeling. It’s a film steeped in the stark beauty and existential dread of McCarthy's prose, but it also carries the undeniable ghost of a different, perhaps grander, movie – the one the studio wouldn't let us see. This one landed right at the cusp of the DVD era, but its heart feels older, belonging to a tradition of sweeping Westerns, albeit one filtered through a lens of modern disillusionment. For many of us, it was likely one of the last 'new releases' we might have picked up on trusty VHS.

Across the Border, Into the Dust

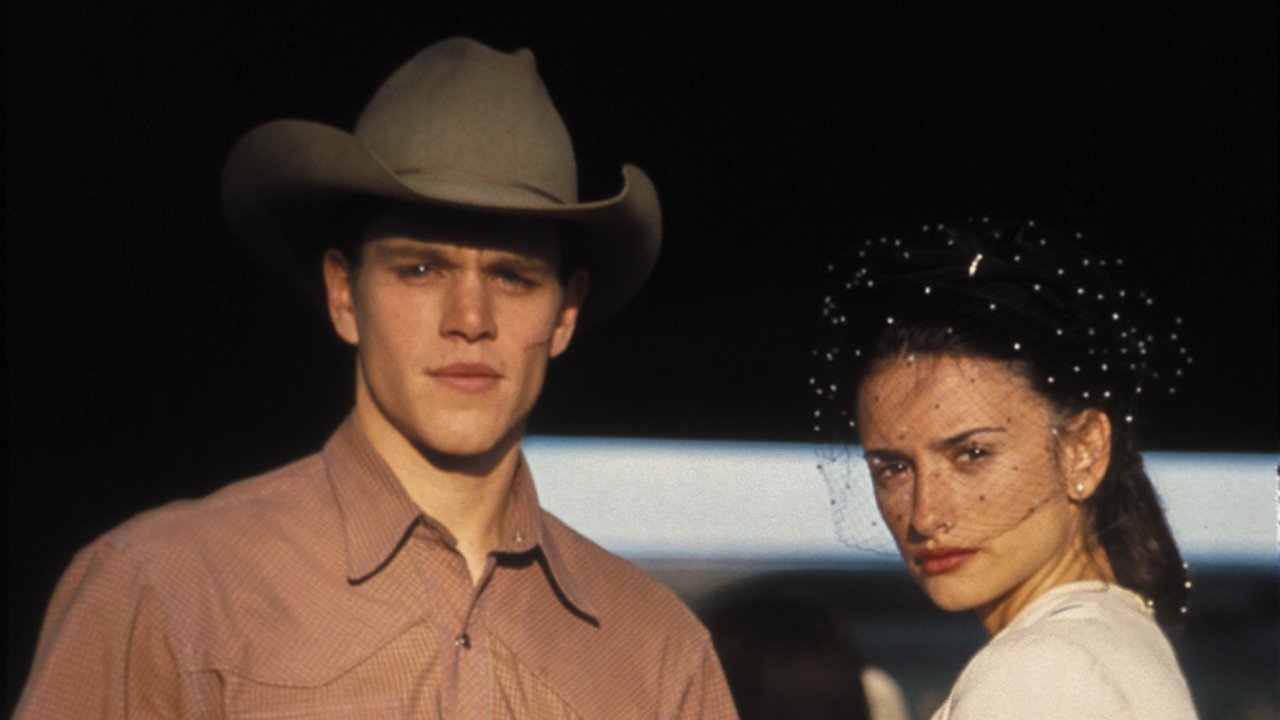

The premise itself is pure, yearning Americana, twisted by McCarthy's unsparing worldview. It’s 1949, and young Texan John Grady Cole (Matt Damon) finds his ancestral ranch sold, his way of life evaporating. Alongside his friend Lacey Rawlins (Henry Thomas – yes, Elliott from E.T., all grown up and facing a different kind of alien landscape), he rides south into Mexico, seeking work, adventure, and perhaps a connection to a fading cowboy ideal. They find work on a vast hacienda, and John Grady finds Alejandra (Penélope Cruz), the hacendado's daughter, igniting a passionate but forbidden romance that sets them all on a collision course with the harsh realities of this new land.

The Weight of the Word

Adapting Cormac McCarthy is no small feat. His language is poetic yet brutal, his landscapes vast and unforgiving, his themes elemental. Ted Tally, who so brilliantly brought Thomas Harris's darkness to life in The Silence of the Lambs (1991), faced a different challenge here: translating McCarthy's internal monologues and mythic atmosphere into visual storytelling. Thornton, fresh off the critical success of Sling Blade (1996), clearly aimed for an epic scope, mirroring the novel’s meditative pace and philosophical weight. The film looks magnificent, with cinematographer Barry Markowitz painting stunning vistas of Texas and New Mexico (standing in for Mexico) that capture the allure and isolation drawing the boys south. You can almost feel the sun, the dust, the sheer scale of the world they've entered.

The Phantom Edit (Retro Fun Facts)

But here’s where the melancholy deepens. All the Pretty Horses became infamous for its post-production battles. Thornton delivered a cut reportedly close to four hours long, aiming for a faithful, immersive experience. Miramax, then under Harvey Weinstein, balked. Heavy pressure led to the film being slashed to its current 116-minute runtime. Imagine nearly half the story, half the character development, half the atmosphere, simply gone. This wasn't just trimming; it was cinematic surgery without anesthetic. One casualty was much of the original score by Daniel Lanois (though thankfully some cues remain, adding haunting texture), replaced by more conventional music.

The impact is palpable. Scenes feel abrupt, emotional transitions sometimes jarring, and crucial character motivations (especially Alejandra’s) can feel underdeveloped. What should feel like a slow burn descent into tragedy occasionally feels like a highlights reel. The film, budgeted at a hefty $57 million (around $100 million today), ultimately struggled at the box office, pulling in only $18 million worldwide. Initial reviews reflected this dichotomy: praise for the visuals and Damon’s performance often sat alongside criticism of the choppy narrative. Knowing this history transforms the viewing experience; you're constantly sensing the missing pieces, the phantom limbs of the larger story.

Faces Weathered by Fate

Despite the compromised structure, the performances anchor the film. Matt Damon, then solidifying his leading man status post-Good Will Hunting (1997) and Saving Private Ryan (1998), embodies John Grady's stoic idealism and quiet intensity. He carries the weight of McCarthy's world-weary young protagonist admirably, conveying deep emotion through subtle glances and quiet resolve. Penélope Cruz, on the cusp of international stardom, is luminous and magnetic as Alejandra, even if the script's truncation leaves her character feeling more like a catalyst than a fully explored person. And Henry Thomas provides a crucial counterpoint as Lacey, the more pragmatic, perhaps more easily broken, friend. His journey from hopeful companion to traumatized survivor is one of the film's more affecting, albeit compressed, arcs.

A Flawed Beauty

So, what are we left with? All the Pretty Horses is undeniably beautiful. The cinematography is breathtaking, capturing the romanticism of the West even as the story dismantles it. There are moments of genuine power: the raw intensity of the prison sequences, the quiet despair in Damon’s eyes, the potent sense of loss that permeates the final act. Thornton's reverence for the source material shines through in the film's tone and visual poetry. It feels like a Cormac McCarthy story, even if it’s an abridged one.

Does the knowledge of the studio interference excuse the film's narrative shortcomings? Not entirely. The released version has undeniable pacing issues and underdeveloped threads. Yet, there's a nobility in its ambition, a sincerity in its performances, and a visual grandeur that sticks with you. It’s a film that makes you ache, not just for its characters, but for the fuller experience that might have been. It occupies a strange space – too polished perhaps for some cult classic lists, too compromised for unqualified masterpiece status.

Rating: 6/10

Justification: The score reflects a film caught between ambition and interference. The stunning cinematography, committed performances (especially Damon's), and palpable McCarthy atmosphere earn significant points. However, the heavily compromised edit demonstrably harms the pacing, character depth, and overall narrative coherence, preventing it from reaching the heights it clearly aimed for. It’s a film whose beauty is constantly undercut by the feeling of missing pieces.

Final Thought: All the Pretty Horses remains a haunting 'what if' of modern cinema – a visually rich, emotionally resonant fragment that makes you forever wonder about the epic that got away.