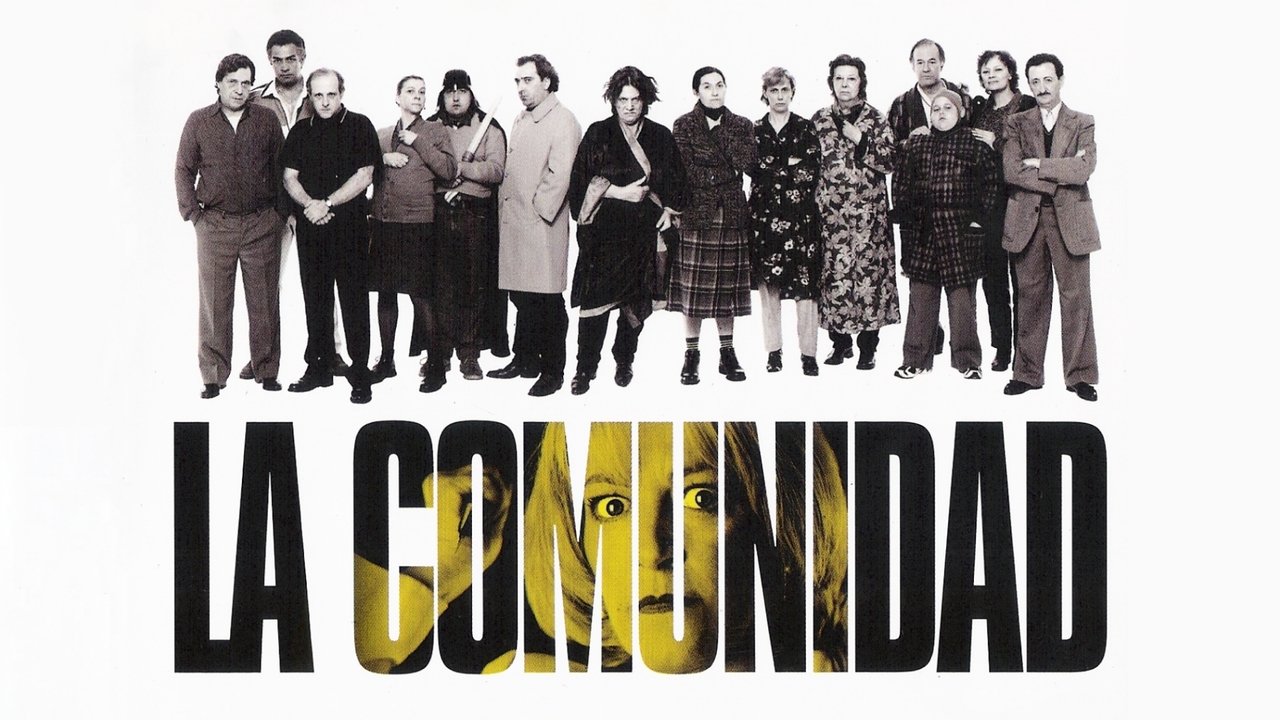

It often starts innocently enough, doesn't it? A dripping tap, a strange noise through the paper-thin walls of apartment living. But what happens when the hole you investigate reveals not just faulty plumbing, but a dead neighbour and a hidden fortune large enough to change your life forever? This is the wickedly dark premise dropped into the lap of Julia, the struggling real estate agent at the heart of Álex de la Iglesia's 2000 Spanish thriller, Common Wealth (original title: La Comunidad). Released right at the cusp of a new millennium, this film feels like a spiritual sibling to the cynical, sharp-edged genre pieces we devoured on tape throughout the 90s, albeit with a distinctly European flavour and a biting satirical edge that still draws blood.

A Community of Vultures

De la Iglesia, who already gave us the brilliant satanic absurdity of The Day of the Beast (1995), teams up again with his frequent writing partner Jorge Guerricaechevarría to craft a narrative that peels back the veneer of neighbourly politeness with surgical, almost gleeful, precision. Julia, played with frantic energy and desperate relatability by the legendary Carmen Maura (an icon cemented by her work with Almodóvar), thinks she’s hit the jackpot when she discovers 300 million pesetas stashed in the deceased man's apartment she’s trying to sell. Her dreams of escaping her loveless marriage and mundane existence seem within reach. But there’s a catch, isn’t there always? The entire eccentric, cash-strapped, and morally bankrupt community of residents in the building knows about the money – they were just waiting for the old man to die. And they are not about to let an outsider swoop in and claim their prize.

What unfolds is less a straightforward thriller and more a pressure-cooker black comedy, a descent into a claustrophobic hell of shared hallways and simmering resentment. The apartment building itself becomes a character – a decaying, labyrinthine space reflecting the warped souls within it. De la Iglesia masterfully uses the setting, amplifying the sense that there is no escape, each neighbour a potential threat, every shared glance loaded with suspicion. You can almost smell the stale air and desperation. It taps into that primal fear of being surrounded, outnumbered, your good fortune becoming the very thing that paints a target on your back. Doesn't this intense microcosm of greed feel disturbingly familiar, reflecting broader societal tensions?

Carmen Maura's Desperate Dance

At the centre of this vortex is Carmen Maura. Her performance is a tightrope walk between victimhood and calculating self-interest. Julia isn't a pure soul corrupted; she’s flawed, weary, and sees the money as her only way out. Maura makes you feel her panic, her moments of cunning, her sheer terror as the neighbours close in. It’s a physically demanding role, too, involving frantic chases, hiding, and eventually, outright battle. She earned a Goya Award (Spain's equivalent of the Oscar) for Best Actress for this, and it’s easy to see why. She anchors the escalating madness with a believable human core, even as the situation spirals into grotesque absurdity.

The supporting cast, portraying the titular "community," are a gallery of grotesques, each embodying a particular shade of avarice and petty grievance. From the domineering Señora Ramona (María Asquerino) to the various oddballs and schemers, they form a formidable, almost hive-mind-like antagonist. They are funny, yes, in a deeply uncomfortable way, but also genuinely menacing. Their collective desire for the money transforms neighbourly disputes into something primal and dangerous.

Style and Substance

De la Iglesia’s direction is kinetic and stylish, but never at the expense of tension. He knows how to build suspense through tight framing, unsettling camera angles, and sharp editing. There are sequences here – particularly a harrowing escape across the rooftops – that recall Hitchcock in their construction, blending nerve-shredding suspense with moments of unexpected, dark humour. While released in 2000, the film retains a certain gritty texture that feels akin to late 90s thrillers, before digital gloss became ubiquitous. It’s a tactile film, grounded in its squalid reality even as the plot escalates.

Interestingly, the film cost around €3.6 million to make and became a significant hit in Spain. It wasn't just the thrills; its cynical take on community and the corrupting influence of money clearly struck a chord. Perhaps it tapped into anxieties simmering beneath the surface of Spain's economic boom at the time? Watching it now, the themes feel depressingly timeless. What wouldn't people do for a life-changing sum of money, especially when they feel entitled to it?

A Hidden Gem Worth Unearthing

Common Wealth might have slipped under the radar for some, perhaps overshadowed by bigger Hollywood releases or arriving just as the VHS era was truly winding down, giving way to DVD. I remember finally catching it on a rental DVD, intrigued by de la Iglesia's name after The Day of the Beast, and being absolutely gripped by its relentless pace and biting wit. It’s the kind of film that feels like a discovery – smart, nasty, funny, and surprisingly thrilling. It lacks the outright supernatural elements of some of de la Iglesia's other work, grounding its horror firmly in human greed.

It's a film that doesn't offer easy answers or comforting resolutions. It stares into the abyss of human nature when neighbourly bonds dissolve under the weight of sudden wealth, and it doesn't blink. The dark humour prevents it from becoming overwhelmingly bleak, but the underlying cynicism leaves a mark.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects a tightly constructed, brilliantly acted, and wickedly entertaining thriller that masterfully blends suspense and black comedy. Carmen Maura delivers a powerhouse performance, and Álex de la Iglesia directs with kinetic energy and a sharp satirical eye. Its claustrophobic atmosphere and cynical take on community are highly effective, making the apartment building itself a memorable antagonist. While its bleakness might not be for everyone, its skill and thematic resonance are undeniable. It’s a standout piece of Spanish genre cinema from the turn of the millennium.

What lingers most after the credits roll? Perhaps the unsettling thought that the thin walls separating us from our neighbours might hide more than just noise – they might hide a shared capacity for desperation and greed, waiting for the right (or wrong) opportunity to emerge. A potent, unsettling gem.