There's a certain quiet confidence, isn't there, in the way Claude Chabrol lets a story unfold? It's less about frantic action and more about the intricate dance of human behavior, the subtle shifts in power and trust. Watching The Swindle (originally Rien ne va plus, 1997) again after all these years, pulling that tape off the shelf feels less like revisiting a heist movie and more like eavesdropping on a peculiar, long-standing relationship built on petty crime and unspoken affections. It’s a film that likely sat alluringly on the video store shelf, perhaps promising a straightforward caper, only to deliver something far more nuanced and deceptively complex.

A Partnership Forged in Deceit

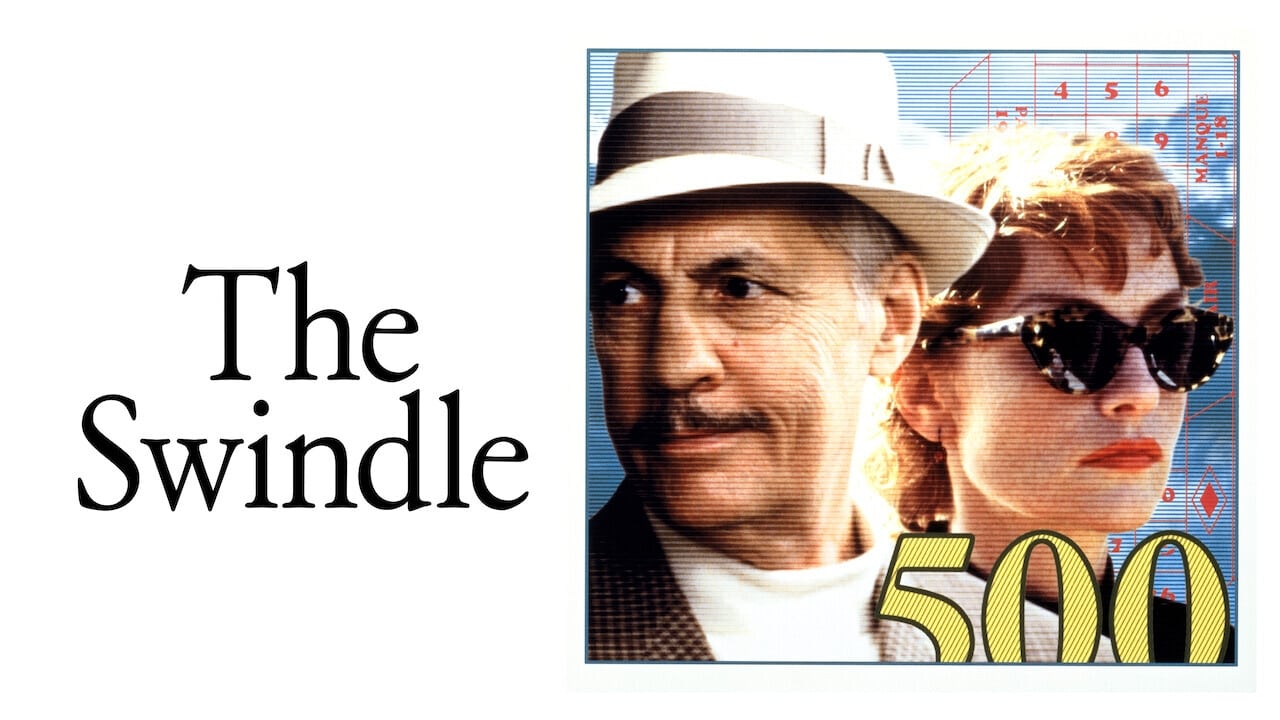

At the heart of The Swindle are Betty, played by the incomparable Isabelle Huppert, and Victor, embodied with weary charm by the great Michel Serrault. They aren't master criminals pulling off multi-million dollar heists; their game is smaller, more intimate. Betty uses her allure to target attendees at business conferences, setting them up for Victor to swoop in, often posing as a concerned relative or authority figure, relieving them of their cash. There’s a practiced rhythm to their routine, a comfortable symbiosis built over years. You sense a history there, a father-daughter dynamic perhaps, or something murkier, less defined. Chabrol, ever the master of ambiguity, leaves it tantalizingly unclear.

What makes it captivating is watching these two veterans navigate their roles, both within the cons and within their own peculiar relationship. Huppert, who worked frequently with Chabrol (their chilling collaboration La Cérémonie hit screens just two years prior in 1995), is mesmerizing. She shifts effortlessly from vulnerable target to cool manipulator, her expressive face a canvas of calculated emotion. Serrault, a titan of French cinema perhaps best known internationally for La Cage aux Folles (1978), perfectly captures Victor's blend of paternalism, anxiety, and cunning. He’s the steady, slightly rumpled hand guiding their small enterprise, yet there's a constant flicker of worry in his eyes – is Betty getting too ambitious? Is their luck about to run out?

When the Stakes Get Real

Their established pattern gets disrupted when Betty sets her sights on Maurice (François Cluzet, another fine French actor), a seemingly ordinary corporate treasurer handling a large sum of offshore money. Suddenly, the small cons escalate into potentially dangerous territory involving Caribbean banks and shadowy figures. This is where Chabrol's genius truly lies. He doesn't ratchet up the action in a typical Hollywood fashion. Instead, the tension builds through psychological pressure, through shifting alliances and the ever-present question of who is conning whom. The original French title, Rien ne va plus, translates to "no more bets" – the croupier's call in roulette. It’s a perfect metaphor for the moment their familiar game spins potentially out of control.

Chabrol's Observational Eye

This isn't a film that relies on flashy editing or explosive set pieces. Chabrol's direction is classically precise, almost detached. He observes his characters with a cool, sometimes wryly amused eye, often setting their amoral activities against picturesque Swiss or Guadeloupean backdrops. It’s a technique he honed throughout his career, finding the darkness lurking beneath placid surfaces. The pacing is deliberate, allowing the nuances of the performances and the subtleties of the plot twists to breathe.

It’s fascinating to know that Chabrol reportedly wrote the script specifically with Huppert and Serrault in mind. You can feel it in the way the dialogue and situations perfectly play to their strengths, allowing their intricate chemistry to carry the film. It’s not just about the plot; it’s about watching these two characters orbit each other, their motivations remaining wonderfully opaque until the very end. It's a testament to the film's quiet power that it scooped the Golden Shell, the top prize at the San Sebastian International Film Festival.

A Different Kind of Thrill

For those of us browsing the aisles of "VHS Heaven," The Swindle represents a different kind of 90s thriller. It lacks the pyrotechnics of its American counterparts, but offers something richer, more lasting. It engages the mind more than the adrenaline glands. What truly resonates is the exploration of trust, or the profound lack of it, within this strange partnership. Can two people whose entire existence is based on deception ever truly rely on each other? What happens when genuine emotion – or the appearance of it – enters their carefully constructed world?

The film might not have been a blockbuster, made on a budget that would barely cover the catering on a Hollywood production of the era, but its value lies in its craftsmanship and its unforgettable central duo. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most compelling conflicts are the internal ones, the unspoken battles waged behind careful smiles and practiced lies.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's superb central performances, Chabrol's masterful, understated direction, and its intelligent, character-driven approach to the crime genre. It’s a sophisticated, wryly observed piece that might require a bit more patience than your average 90s caper, but the payoff in psychological depth and performance artistry is substantial. It loses a couple of points perhaps for a slightly meandering middle section, but the strength of the leads pulls it through decisively.

Final Thought: The Swindle lingers not because of the complexity of the con, but because of the enduring enigma of Betty and Victor – a partnership as fragile and fascinating as a house of cards built on a roulette table just before the ball drops.