Does a film truly capture a life, especially one lived as a deliberate enigma? Watching Miloš Forman's Man on the Moon again, nearly a quarter-century after its release, that question hangs heavy in the air, thick as the cigarette smoke in the comedy clubs Andy Kaufman once haunted. It’s less a straightforward biopic and more an elaborate performance piece about a performer whose ultimate act was blurring the line between himself and his creations, leaving us perpetually unsure where Andy ended and the Kaufman persona began. It arrived just as the VHS era was winding down, a challenging, often uncomfortable film that felt strangely out of step even then, demanding more from its audience than the usual rise-and-fall celebrity narrative.

The Unfilmable Subject?

Andy Kaufman was never just a comedian; he was a performance artist disguised as one, a provocateur who seemed to actively court confusion and alienation alongside laughter. How do you bottle that lightning – the awkward silences, the baffling character shifts from the wide-eyed 'Foreign Man' to the obnoxious lounge lizard Tony Clifton, the wrestling stunts that alienated half his audience? Writers Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, who had already proven their knack for sympathetically portraying cultural outsiders with Ed Wood (1994), lean into the chaos. They don't try to neatly explain Kaufman; instead, they present his most famous (and infamous) moments, letting the contradictions stand. It’s a structure that mirrors Kaufman’s own fractured approach to entertainment, a series of vignettes rather than a smooth arc. Does this mean we truly understand him by the end? Perhaps not. But maybe, as the film suggests, understanding wasn't the point Kaufman was trying to make.

Carrey's Disappearing Act

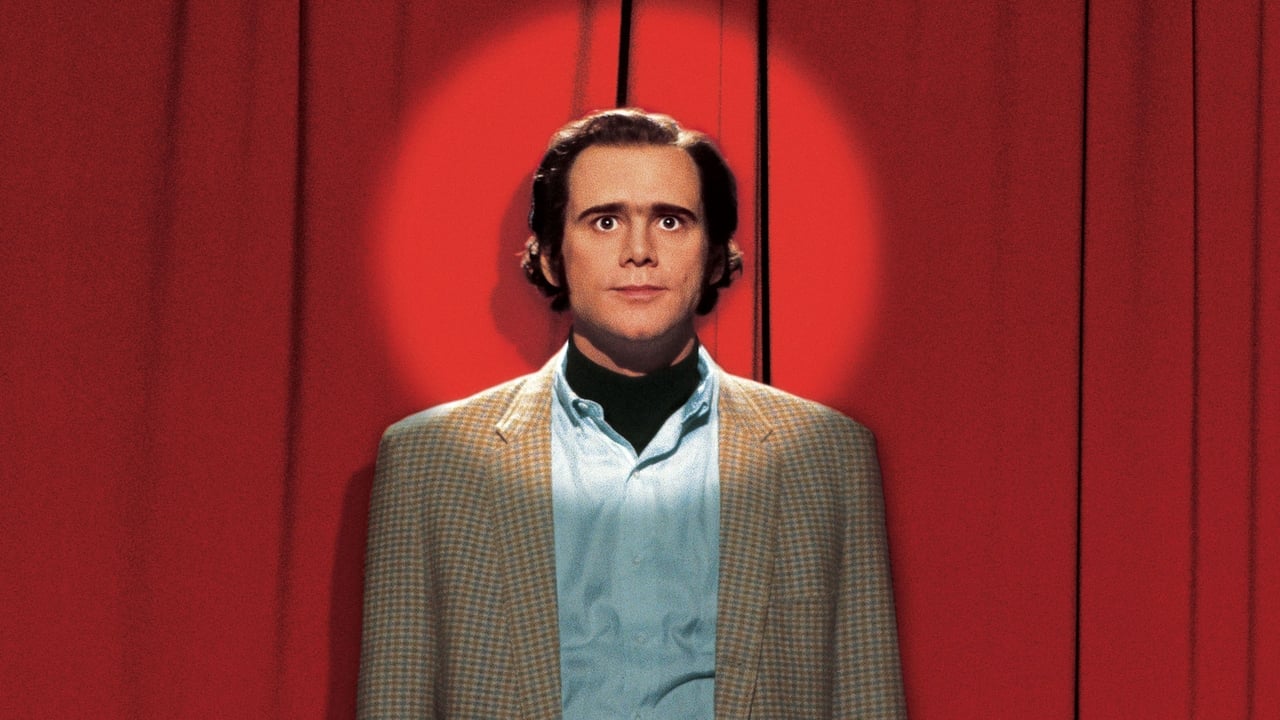

At the center of this whirlwind is Jim Carrey, and it's impossible to discuss Man on the Moon without grappling with his monumental, almost terrifyingly immersive performance. Fresh off mainstream smashes like Liar Liar (1997) and the more contemplative The Truman Show (1998), Carrey didn't just play Andy Kaufman; by all accounts, he became him (and often, the abrasive Tony Clifton) on set, blurring the lines just as Kaufman did. While the stories of his method approach are now well-documented, what matters is what’s on screen. It’s a transformation that goes beyond mimicry. Carrey captures Kaufman's peculiar energy – the childlike vulnerability one moment, the aggressive hostility the next. He nails the voices, the mannerisms, but more crucially, he embodies the commitment Kaufman had to his bits, no matter how alienating. It's a performance that earned him a Golden Globe but, bafflingly to many at the time, no Oscar nomination. Watching it now, it feels less like acting and more like channeling. The sheer audacity is undeniable, even if it sometimes feels like we're watching Jim Carrey being Andy Kaufman, rather than simply playing him – a meta-layer Kaufman himself might have appreciated.

Forman's Steady Hand in the Storm

Overseeing this was Miloš Forman, a director famed for chronicling rebellion and genius against the grain (One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975), Amadeus (1984)). His steady, almost classical style provides an interesting counterpoint to Kaufman's anarchy. Forman doesn't impose a flashy directorial signature; he lets the performances and the recreated moments speak for themselves. This sometimes results in a slightly disjointed feel, a sense that the conventional biopic framework is struggling to contain its unconventional subject. Yet, Forman’s skill lies in capturing the human moments amidst the performance art – Kaufman’s relationship with his manager George Shapiro (a warm, grounding Danny DeVito, who knew the real Kaufman from their Taxi days) and his girlfriend Lynne Margulies (Courtney Love, surprisingly effective and vulnerable). A fascinating touch was Forman’s decision to populate the film with many of Kaufman's actual colleagues playing themselves – Judd Hirsch, Marilu Henner, Christopher Lloyd, Carol Kane, wrestling legend Jerry "The King" Lawler, even David Letterman. This adds a layer of eerie authenticity, blurring the past and its recreation right before our eyes.

Reliving the Confusion

I distinctly remember renting this on VHS, probably expecting a zany Jim Carrey comedy, and being utterly bewildered. It wasn't laugh-out-loud funny in the way Ace Ventura was; it was something stranger, sadder, more complex. The film perfectly recreates that sense of watching Kaufman on Saturday Night Live or Fridays back in the day – the feeling of "What am I watching? Is this supposed to be funny?". It captures the hostility of the Tony Clifton character, the bizarre commitment to the intergender wrestling saga, and the profound discomfort of his final Carnegie Hall performance, where he genuinely seemed to be wrestling with his own mortality. The use of R.E.M.'s music, particularly the haunting title track "Man on the Moon" and the specifically written "The Great Beyond," adds immeasurably to the film's melancholic, searching atmosphere. It’s a film that cost a reported $52 million but struggled to find its audience, grossing only $47 million worldwide – perhaps a testament to how successfully it channeled Kaufman’s own challenging relationship with mainstream appeal.

Lasting Impressions

Man on the Moon isn't a perfect film. It sometimes feels episodic, and it offers few easy answers about its subject's motivations. Yet, its power lies in its refusal to sanitize or simplify Andy Kaufman. It embraces the weirdness, the discomfort, and the profound questions Kaufman's life and career provoked about the nature of identity, performance, and the contract between entertainer and audience. Carrey's performance remains a towering achievement, a full-bodied immersion that is both magnetic and unsettling.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's ambition, its unforgettable central performance, and its courageous commitment to portraying an artist who defied easy categorization. While the somewhat conventional structure occasionally clashes with the subject's unconventional nature, and it might leave viewers more perplexed than enlightened (which, arguably, is fitting), the sheer force of Carrey's transformation and Forman's skillful recreation of Kaufman's world make it a compelling and essential watch. It remains a fascinating artifact from the turn of the millennium – a major studio biopic that dared to be as strange and provocative as the man himself. Did Andy Kaufman fake his own death? The film leaves it, like so much else, beautifully, maddeningly ambiguous.