It’s strange, isn't it, how some images lodge themselves in your memory? Not necessarily the explosive set pieces or the perfectly delivered punchlines we often sought on those Friday night trips to the video store, but something quieter, more unsettling. A flickering image on a CRT screen that suggested the world outside the multiplex was far more complex, and perhaps more disturbing, than we usually cared to admit. For me, encountering Tatsuya Mori's 1998 documentary, simply titled A, was one such experience. This wasn't a tape you grabbed for escapism; it was one that demanded your attention, pulling you into a space most would instinctively avoid.

Into the Eye of the Storm

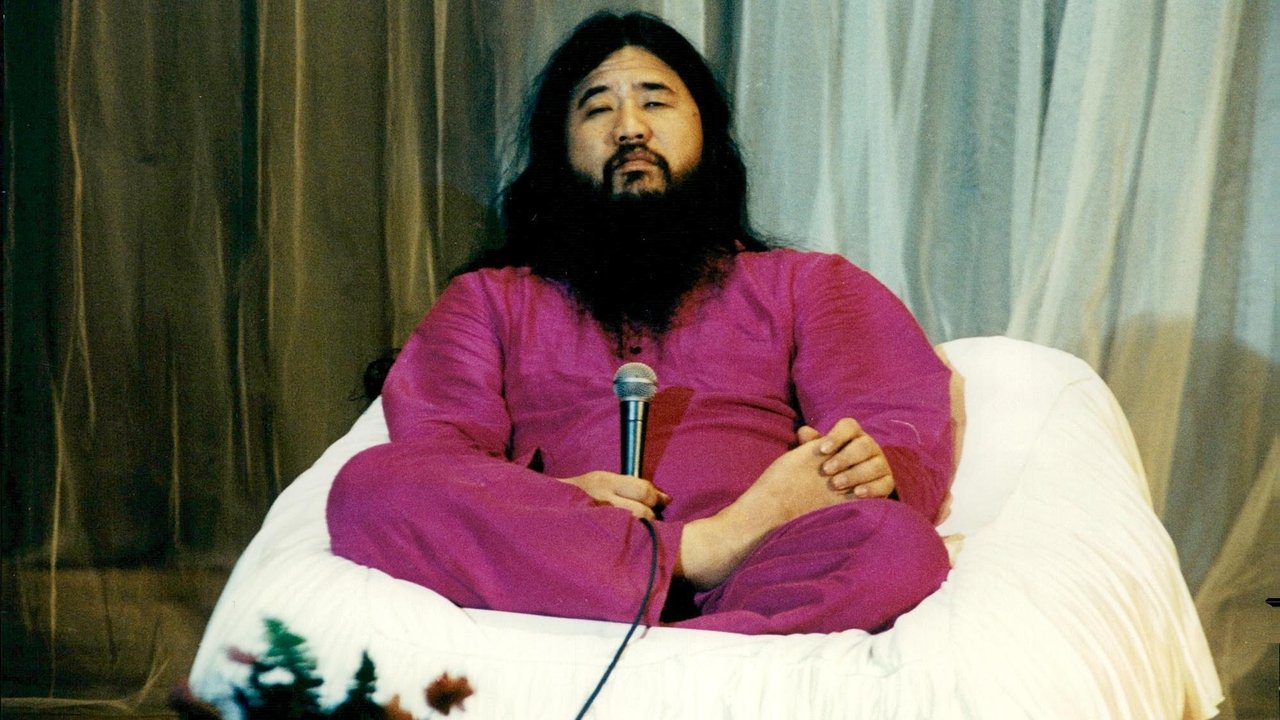

The premise alone was audacious, almost unthinkable in the wake of the horrifying 1995 Tokyo subway sarin attack: Tatsuya Mori gained intimate, prolonged access to the Aum Shinrikyo cult after the attack. He didn't focus on the imprisoned leader, Shoko Asahara, or rehash the details of the atrocity. Instead, his camera primarily follows Hiroshi Araki, the cult's young, surprisingly articulate public relations spokesman, along with other remaining members, as they navigate the intense media scrutiny, public hatred, and police surveillance that became their daily reality.

Watching A now, decades removed from the immediate shock of the Aum incident, is still a profoundly uncomfortable experience. Mori adopts a direct cinema approach – observational, patient, rarely intervening directly. He simply films. He films Araki dealing with aggressive reporters, fielding hostile phone calls, interacting politely with police officers conducting searches, and engaging in mundane conversations with fellow believers holed up in their commune-like headquarters. There’s a chilling banality to much of it. We see them eating, cleaning, discussing logistics – activities stripped bare of the monstrous label the world had assigned them.

The Uncomfortable Question of Seeing

What makes A so compelling, and indeed so controversial, is its refusal to demonize its subjects outright. Mori’s lens doesn’t excuse Aum’s actions, nor does it explicitly condemn the individuals remaining within its fold. Instead, it forces us, the viewers, into an uncomfortable proximity. We witness Hiroshi Araki’s attempts at reasoning, his moments of frustration, his quiet persistence. Is he brainwashed? A calculating manipulator? Simply a young man clinging to the only community he knows? The film offers no easy answers, and that ambiguity is precisely its power.

It challenges our tendency, amplified then by sensationalist 90s media cycles and perhaps even more so today, to flatten complex human realities into easily digestible narratives of pure good versus pure evil. By showing the daily life within the Aum compound – the shared meals, the anxieties, the attempts at maintaining normalcy under siege – Mori raises profound questions. How does belief function under extreme pressure? What does it mean to belong, even to a group universally reviled? Doesn't the relentless media hounding, captured unflinchingly by Mori, sometimes cross a line itself, bordering on a collective societal exorcism?

Beyond the Headlines

Finding detailed "behind-the-scenes" trivia for a film like A is different from digging into a Hollywood blockbuster. The context is the story. Tatsuya Mori, a former documentary director for television, reportedly secured access through sheer persistence and perhaps a willingness to listen when everyone else was shouting. He filmed for roughly two years, accumulating hundreds of hours of footage. The production itself was fraught; Mori faced suspicion from both Aum members wary of his intentions and authorities monitoring the group. Its release in Japan was, unsurprisingly, met with significant controversy, with some cinemas refusing to screen it, fearing backlash or accusing Mori of being overly sympathetic. Yet, it won awards, including at the Berlin International Film Festival, recognizing its courageous and nuanced approach. It’s a stark reminder that documentary filmmaking, especially on sensitive topics, often involves navigating immense ethical and practical challenges. Mori would later revisit the subject in A2 (2001), continuing his exploration.

A Mirror to Ourselves?

A isn't a film you "enjoy" in the conventional sense. It's probing, unsettling, and deeply thought-provoking. It doesn’t offer the catharsis of a thriller or the comfort of a comedy. Instead, it holds up a mirror, not just to the specific events surrounding Aum Shinrikyo, but to broader human tendencies: how societies react to fear, how media shapes perception, and the difficult, often blurred line between understanding and condoning. Watching it feels like handling a delicate, perhaps dangerous, historical artifact – a window into a specific moment of collective trauma and the complex human ripples spreading from it.

It stands as a powerful example of late-90s documentary filmmaking pushing boundaries, demanding more from its audience than passive consumption. It reminds us that sometimes, the most important stories are the ones that make us profoundly uneasy, forcing us to confront uncomfortable truths about the world and, perhaps, ourselves.

Rating: 9/10

A earns this high rating not for being entertaining, but for its sheer audacity, its rigorous observational approach, and its profound, enduring questions. Tatsuya Mori’s bravery in gaining access and his disciplined refusal to provide easy answers make this a landmark documentary. Its power lies in its quiet intensity and the uncomfortable ambiguity it forces upon the viewer, challenging simplistic notions of guilt, belief, and societal response. It's a demanding watch, far removed from typical VHS comfort food, but its importance and filmmaking craft are undeniable.

Final Thought: How willing are we, truly, to look closely at those we deem monstrous, and what might we learn – about them, and about ourselves – if we do?