Okay, pull up a comfy chair, maybe grab a dusty tape from the shelf – let's talk about a sequel that arrived almost like a rumour whispered across video store aisles, decades after its iconic predecessor. I’m talking about To Sir, with Love II, which landed on our CRT screens in 1996, a full twenty-nine years after Sidney Poitier first charmed and challenged a classroom of unruly East End London teens. The very existence of this follow-up prompts a question, doesn't it? Can lightning really strike twice, especially when separated by such a vast gulf of time and cultural change?

From Swinging London to 90s Chicago

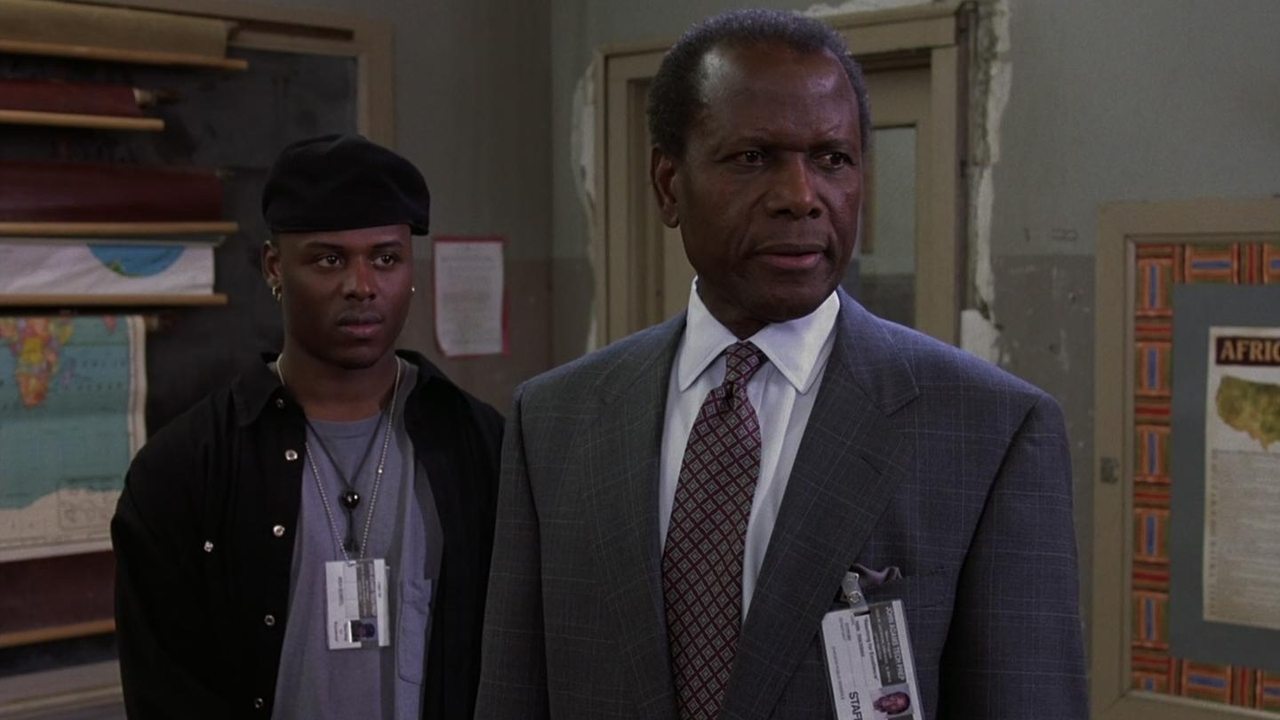

The setup immediately signals the shift. Mark Thackeray (Sidney Poitier), now retired from his teaching career in London, is drawn back into the fray, this time in the tough environment of an inner-city Chicago high school. Gone are the cheeky mods and beehives of the 60s; enter the baggy jeans, burgeoning hip-hop culture, and starker socio-economic realities of mid-90s America. It’s a bold move, attempting to transplant Thackeray’s unique brand of tough love and mutual respect into a radically different landscape. This wasn't just a change of scenery; it felt like a change of planet sometimes.

Interestingly, the project wasn’t just a studio whim. E.R. Braithwaite, the author whose autobiographical novel inspired the original film, actually co-wrote the teleplay for this sequel alongside Philip Rosenberg. Having the original author involved lends a certain weight, a feeling that perhaps Thackeray’s journey wasn’t quite finished in his mind. Yet, the film, directed by none other than Peter Bogdanovich (The Last Picture Show (1971), Paper Moon (1973)), aired as a CBS television movie, a detail that immediately sets expectations. Could the nuanced character study and quiet power of the original truly translate to the constraints and perhaps different priorities of network TV in the 90s?

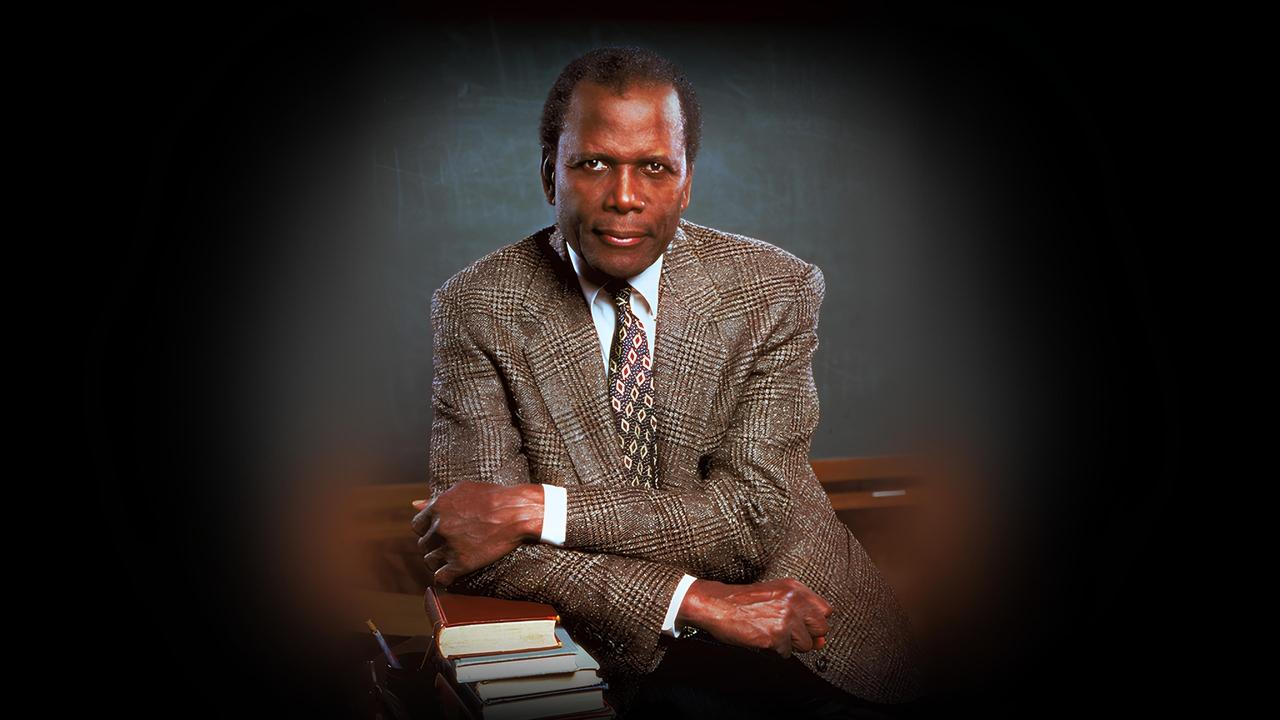

The Enduring Grace of Poitier

Let's be frank: the primary reason to seek out this tape, then or now, is Sidney Poitier. Seeing him step back into Thackeray's shoes is undeniably poignant. He carries the intervening years with a quiet dignity, his familiar presence a comforting anchor. Poitier doesn't try to simply replicate his younger self; there’s a weariness etched alongside the wisdom, a sense that the battles are harder now, the cynicism deeper among his students. He brings an inherent gravitas that elevates the material considerably. Watching him navigate the challenges of this new environment – trying to connect with kids hardened by violence, poverty, and systemic neglect – is where the film finds its most compelling moments. His performance feels authentic, a man wrestling with whether his old methods still hold water in a world that feels increasingly fractured. Does that patient insistence on respect and self-worth still resonate when survival seems like the only lesson worth learning?

A Different Classroom, A Different Battle

The students here are facing different demons than their London counterparts. Issues of gang violence, racial tension within the student body itself, and profound disillusionment are front and centre. The film deserves credit for not shying away from these tougher realities, even within its TV movie framework. The dynamic is less about breaking down class barriers (though that's still present) and more about piercing the armour of trauma and distrust. We see familiar archetypes – the tough leader (played with intensity by Christian Payton), the quietly observant student, the one desperately seeking a way out – but the context feels heavier, the stakes arguably higher. Daniel J. Travanti (Hill Street Blues) also provides solid support as the initially skeptical principal.

However, the script sometimes struggles to give these complex issues the depth they deserve, occasionally leaning into predictable plot points or slightly didactic speeches. Perhaps it’s the episodic nature inherent in its TV movie origins, or maybe it’s just incredibly difficult to recapture the specific alchemy of the original. The 1967 film felt like a cultural moment, perfectly capturing a generational shift with a charm and optimism that resonated deeply, boosted immensely by Lulu's iconic, chart-topping theme song. This sequel, while earnest, lacks that same spark, that feeling of capturing lightning in a bottle. There's no equivalent musical moment here that could define a generation, or even a summer.

Bogdanovich Behind the Lens

It's certainly interesting to see Peter Bogdanovich, a director associated with the auteur-driven cinema of the 70s, tackling a TV movie sequel in the 90s. His direction is competent and professional, focusing squarely on the performances, particularly Poitier's. There aren't many stylistic flourishes that scream "Bogdanovich," perhaps suggesting he approached it more as a craftsman fulfilling an assignment. Given his reverence for classic Hollywood, one wonders if the chance to work with a legend like Poitier was the primary draw. There’s a certain workmanlike quality to the filmmaking; it serves the story but rarely elevates it in the way the original's direction felt perfectly attuned to its time and place.

Worth Revisiting?

So, popping this tape into the VCR today... what’s the verdict? "To Sir, with Love II" is undoubtedly overshadowed by its legendary predecessor. It lacks the cultural impact, the infectious charm, and the tight narrative focus of the original. The shift to 90s Chicago presents compelling new challenges, but the execution sometimes feels formulaic, hampered perhaps by its television roots and the sheer impossibility of replicating the '67 magic.

Yet, it's far from a disaster. The core reason for its existence, and its enduring value, is Sidney Poitier. His return to the role is handled with grace, and his performance remains the film's strongest asset. It’s a thoughtful, if not groundbreaking, exploration of whether the core principles of respect, dignity, and education can bridge even the most daunting divides. For fans of Poitier, or those curious about how Thackeray's story continued (with the original author's blessing, no less), it offers a worthwhile, if somewhat melancholy, coda. It reminds us that the work of "Sir" is never truly done.

Rating: 6/10

The score reflects the undeniable power of Sidney Poitier's return and the earnest attempt to grapple with relevant themes, balanced against the film's made-for-TV limitations and its inability to escape the long shadow of the original classic. It’s a sequel that perhaps didn't need to exist, but thanks to Poitier, you're quietly glad it does, serving as a gentle echo rather than a vibrant new song. It leaves you pondering not just Thackeray's journey, but the enduring challenge of reaching young minds across generational and societal divides – a question as relevant now as it was in 1996, or indeed, 1967.