Okay, fellow tapeheads, gather ‘round. Sometimes, digging through those dusty bins at the back of the video store, or maybe scanning the handwritten labels on a traded tape, you unearthed something… special. Not necessarily good, mind you, but special. Something that radiated a weird energy, its cover art promising thrills that the slightly fuzzy tracking lines on your CRT TV might struggle to deliver. Friends, let me tell you about the time I encountered the cinematic enigma known simply as Cruel Jaws (1995). This wasn't just a movie; it felt like finding a bootleg cassette of your favorite band, except instead of killer riffs, it was filled with… well, something else entirely.

### When Bruno Met Jaws (Again, and Again)

First things first: this aquatic nightmare bears the fingerprints of Italian exploitation maestro Bruno Mattei, a director who, shall we say, approached filmmaking with a certain… resourcefulness. Working here under the pseudonym William Snyder (one of several he used), Mattei wasn't just inspired by Spielberg's Jaws; he treated its sequels and a few other shark flicks like a personal stock footage library. Watching Cruel Jaws is less like viewing a cohesive film and more like experiencing a bizarre cinematic collage, stitched together with shameless audacity. Forget homage; this is straight-up highway robbery committed on celluloid, and frankly, it’s kind of breathtaking in its brazenness.

The setup is classic seaside terror: the quaint tourist town of Hampton Bay is gearing up for its annual regatta, but wouldn't you know it, a particularly nasty tiger shark decides it's buffet time. Standing between the beast and beachgoers are the grizzled Sheriff Francis (David Luther), a visiting marine biologist (George Barnes Jr., doing his best), and perhaps most memorably, Dag (Richard Dew), the owner of the local budget SeaWorld who bears an uncanny, and surely entirely coincidental, resemblance to a certain wrestling superstar known for his 24-inch pythons. Oh, and did I mention the Mafia is somehow involved, possibly having created the super-shark by dumping toxic waste? Because of course they are.

### Spot the Scene: A Viewer’s Guide to Cinematic Kleptomania

Let's talk about the real star here: the stolen footage. This isn't subtle, folks. One minute you're watching our low-budget heroes looking concerned on a Florida dock, the next you're suddenly plunged into crystal-clear, professionally shot underwater sequences lifted directly from Jaws (1975), Jaws 2 (1978), and Enzo G. Castellari's infamous Italian Jaws clone, The Last Shark (L'ultimo squalo, 1981) – a film Universal itself successfully sued to block distribution in North America! Mattei even swipes bits from his own earlier, lesser-known shark B-movie, Deep Blood (1990). The mismatch in film stock, lighting, and visual quality is often hilariously jarring. Remember that iconic pier attack from Jaws 2? It’s here. The Orca getting chomped in Jaws? Yep, spliced right in. It becomes a game: "Hey, I know that shot!" This incredible cinematic recycling was, unsurprisingly, a retro fun fact that led to Universal Pictures reportedly taking legal action, which hampered the film’s release in many territories, condemning it primarily to the shadowy realm of straight-to-video obscurity where it truly belongs.

### Performances Hooked on Hope

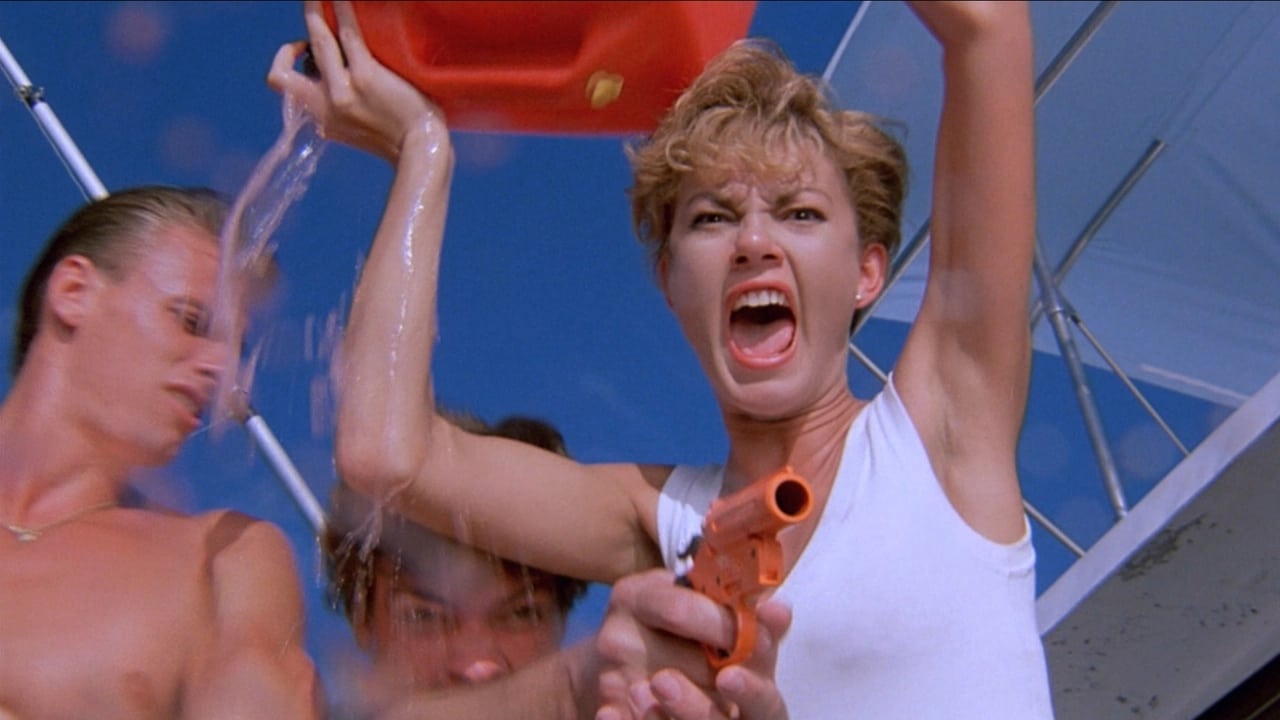

Amidst the chaos of spliced-in terror, the original cast soldiers on with varying degrees of success. David Luther as Sheriff Brody—I mean, Francis—gives it the old college try, looking suitably stressed. The interactions between the main characters feel earnest, if stiffly delivered, like they genuinely believe they're in a serious creature feature. And then there’s Dag. Richard Dew channels the Hulkster with such gusto – the bandana, the handlebar mustache, the sheer larger-than-life presence – that you almost expect him to bodyslam the shark. It’s a performance that transcends the film's limitations through sheer force of personality (or perhaps imitation). You can’t help but smile whenever he’s onscreen, flexing his way through dialogue about marine conservation and imminent shark attacks.

### The "Special" Effects

When Cruel Jaws isn't borrowing from its betters, the "action" involves a rubbery shark head that looks less menacing and more mildly inconvenienced. There are no awe-inspiring practical effects here in the vein of Stan Winston's Bruce. Instead, we get quick cuts, murky water, and that infamous stock footage doing the heavy lifting. While we wax nostalgic about the raw power of 80s practical stunts and explosions, Cruel Jaws serves as a counterpoint – a testament to what happens when the budget barely covers the catering (if there was any). Yet, there's a strange charm to its visible seams. You see the limitations, the frantic cutting to hide the unconvincing prop, the desperate attempts to make disparate scenes feel connected. It’s filmmaking by any means necessary, and the sheer nerve is almost admirable.

### A Treasure Trash Classic?

So, is Cruel Jaws good? By any conventional measure, absolutely not. The plot is nonsensical, the acting is variable, and its core premise is built on theft. Yet… it’s undeniably watchable. It belongs to that hallowed category of "so bad it's good" cinema, perfect for a late-night viewing with friends who appreciate cinematic oddities. It’s a time capsule not just of low-budget 90s filmmaking, but of a wilder, pre-internet era where something this brazen could actually get made and distributed onto video store shelves, waiting to be discovered like a weird, waterlogged message in a bottle. I definitely remember renting tapes like this, drawn in by the lurid cover, hoping for Jaws but getting… well, Cruel Jaws. And honestly? Sometimes that discovery was half the fun.

VHS Heaven Rating: 3/10

Rating Explained: This score reflects the film's technical and narrative failings – it’s objectively poorly made and ethically dubious. However, for sheer unintentional comedy, baffling filmmaking choices, and its legendary status as a "stock footage fiesta," it offers a unique, unforgettable (if bewildering) viewing experience for connoisseurs of cinematic trash.

Final Take: A flick only the VHS era could have produced and protected, Cruel Jaws is less a movie, more a glorious, baffling monument to copyright infringement and low-budget ambition. Approach with caution, a sense of humor, and maybe a checklist of other shark movies.