There's a certain kind of quiet that precedes violence in gangster films, a stillness that often feels more menacing than the eventual explosion. Robert Benton's Billy Bathgate (1991) positively marinates in that quiet. Watching it again, decades after pulling that distinctive VHS box off the rental shelf, I'm struck not by explosive action, but by its pervasive sense of elegy. It’s a film less about the rise and more about the meticulously observed decline, seen through the wide, watchful eyes of a young man stepping into a world already starting to crumble.

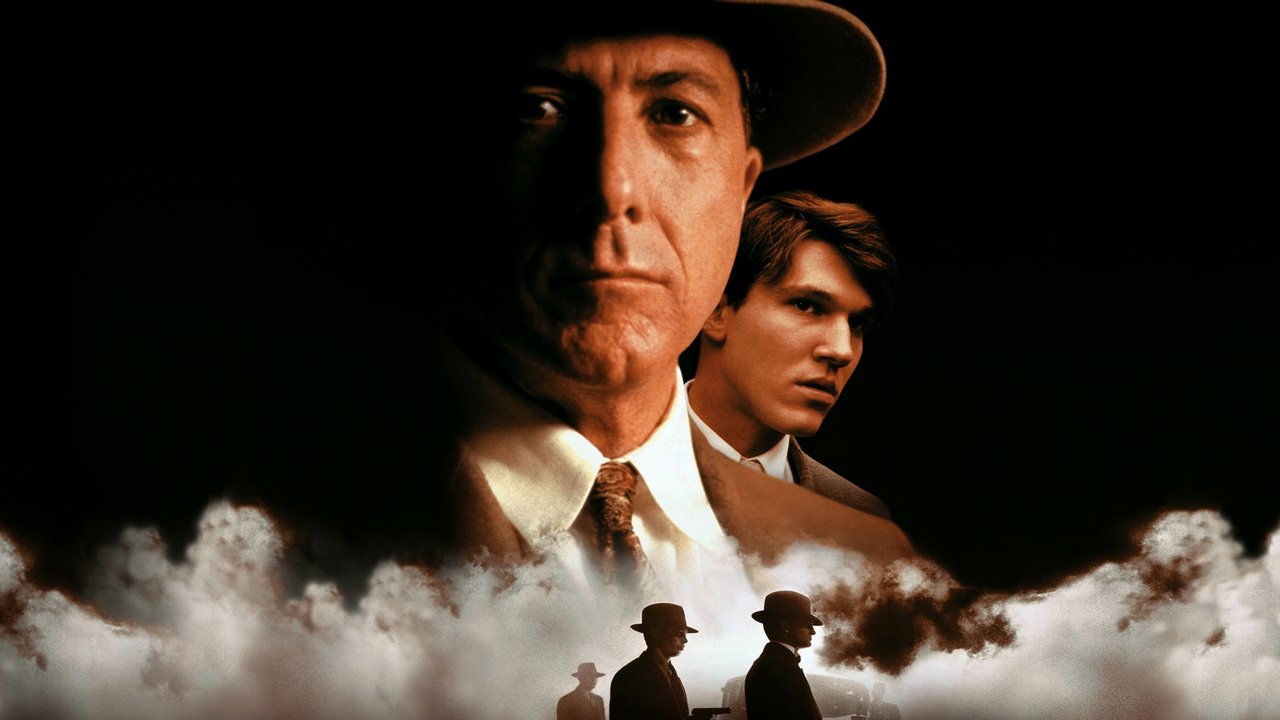

Based on E.L. Doctorow’s celebrated novel and adapted by none other than playwright Tom Stoppard, Billy Bathgate arrived with a pedigree that suggested prestige. Set against the twilight years of Prohibition, it follows young Billy (a fresh-faced Loren Dean), a street-smart kid from the Bronx who literally juggles his way into the inner circle of the notorious gangster Dutch Schultz (Dustin Hoffman). Billy becomes a gofer, an observer, a mascot almost, witnessing the paranoia, the brutality, and the strange codes of honor governing Schultz's doomed empire.

A World Through a Glass, Darkly

What Benton, known for character studies like Kramer vs. Kramer (1979) and Places in the Heart (1984), captures so effectively is the atmosphere. This isn't the kinetic energy of Goodfellas, released just a year prior. Instead, it's draped in the stunning, painterly cinematography of the legendary Nestor Almendros (in what would tragically be his final film). The light seems burnished, autumnal, reflecting the dying gasp of Schultz's reign. Scenes unfold with a deliberate pace, focusing on glances, textures, the weight of unspoken threats. You feel the chill in the air at the upstate New York retreats, the stifling formality of the gangster's court. It’s a gorgeous film to look at, evoking the period with immaculate production design and a keen eye for detail. Perhaps too immaculate? Some critics at the time felt the film’s polished surface kept the viewer at arm's length, a criticism not entirely without merit. Made for a hefty $48 million, its quiet intensity didn't translate into box office gold, barely recouping $15.5 million domestically – a tough outcome for such a star-studded project.

The Dutchman and His Court

At the center, naturally, is Dustin Hoffman as Dutch Schultz. It’s a fascinating performance. Hoffman doesn't go for easy caricature; his Schultz is volatile, yes, prone to sudden, terrifying shifts in mood, but also surprisingly banal at times, almost pathetic in his desperate grasp for control and legitimacy. He's a numbers man consumed by superstition and rage. There's a coiled tension in Hoffman's portrayal, a sense that the violence is always just simmering beneath a tightly controlled surface. It’s not his most beloved role, but it’s a complex and often unsettling piece of work.

Surrounding him is a strong ensemble. Loren Dean carries the weight of being the audience's eyes and ears. He effectively conveys Billy's initial awe slowly curdling into disillusionment and fear, though the character sometimes feels more like a narrative device than a fully fleshed-out individual. Then there's Nicole Kidman as Drew Preston, the kept woman of Schultz's recently dispatched rival, Bo Weinberg (a brief but memorable turn by Bruce Willis, radiating casual menace before his infamous exit). Kidman is luminous, ethereal, gliding through scenes with a kind of detached grace. Drew represents a different kind of danger and allure for Billy, though her character feels somewhat underwritten, more symbol than person. Perhaps the standout, though, is the venerable Steven Hill as Otto Berman, Schultz's loyal consigliere. Hill exudes a quiet wisdom and weary pragmatism that grounds the film; his scenes with Dean, imparting cryptic advice, are among the most compelling.

Echoes in the VHS Static

I remember renting Billy Bathgate back in the day, probably expecting something faster, flashier, more in line with the gangster renaissance happening at the time. It wasn't quite that. It felt... different. More literary, perhaps reflecting Stoppard's involvement. More contemplative. The violence, when it comes (and it does, memorably and brutally, particularly concerning Bo Weinberg’s fate – no spoilers, but it involves water and cement), feels almost depressingly inevitable rather than thrilling. It lacks the propulsive narrative drive of Scorsese or Coppola's masterpieces, opting instead for mood and character moments. This deliberate pacing, which might have felt slow on a Friday night rental back then, plays differently now. It allows the sense of dread and the nuances of the performances to settle. It’s less a rollercoaster, more a slow immersion into a chillingly elegant purgatory. It was filmed primarily on location in Saratoga Springs, New York, and the authenticity of those settings really anchors the period feel, something that translates well even on a lower-resolution format.

A Polished Relic

Is Billy Bathgate a forgotten classic? Not quite. It remains somewhat overshadowed by its contemporaries and perhaps hampered by its own stately reserve. The emotional connection can feel muted at times, the plot occasionally meandering. Yet, there's an undeniable craft and intelligence at work here. It’s a beautifully made film with several powerful performances, particularly Hoffman’s unsettling Schultz and Hill’s stoic Berman. It captures a specific, melancholic mood unlike many other gangster pictures – the feeling of watching powerful men realize, too late, that their time is irrevocably up.

Rating: 7/10

This score reflects the film's undeniable strengths – its gorgeous visuals, strong central performances, and palpable atmosphere – balanced against its narrative detachment and occasional lack of momentum. It doesn't quite reach the heights of the genre's best, but its thoughtful, almost elegiac approach and meticulous craft make it a compelling watch, especially for those seeking a different flavor of 90s gangster movie beyond the usual touchstones.

It lingers not as a thrill ride, but as a portrait of decay, elegantly rendered yet chillingly cold – like a perfectly preserved photograph of a world about to vanish.