Picture this: it’s 1988. The idea of Mickey Mouse sharing screen time with Bugs Bunny feels less like a movie pitch and more like a fever dream born from mixing too many sugary cereals. Yet, somehow, against all odds, it happened. Pulling Who Framed Roger Rabbit from its worn cardboard sleeve and slotting it into the VCR felt like accessing a secret, impossible world – a world where Toons weren't just drawings, but living, breathing (and often chaotic) residents of Hollywood.

This wasn't just another cartoon; it was a revelation. Directed by Robert Zemeckis, hot off the phenomenal success of Back to the Future (1985), and produced under Steven Spielberg's Amblin Entertainment banner, Roger Rabbit was an audacious gamble, a technical marvel wrapped in a surprisingly gritty film noir trench coat. Forget simple animation; this was a seamless, breathtaking blend of live-action grit and hand-drawn mayhem that hadn't just pushed the envelope – it had ripped it wide open.

### Welcome to Toontown Noir

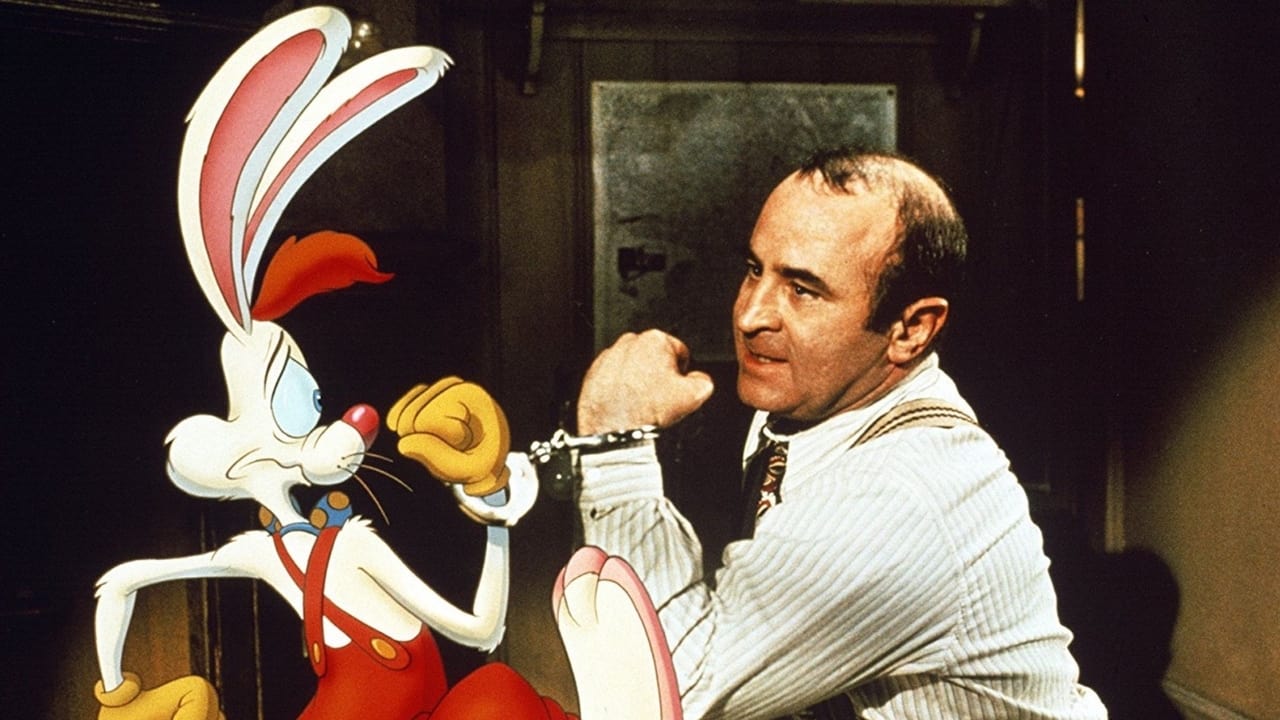

The premise alone is pure gold: In 1947 Los Angeles, cartoon characters ("Toons") coexist with humans. Enter Eddie Valiant (Bob Hoskins), a gruff, booze-soaked private eye nursing a deep-seated grudge against Toons after one killed his brother. He’s hired to get incriminating photos of Jessica Rabbit, the stunningly drawn wife of Maroon Cartoon superstar Roger Rabbit, seemingly playing patty-cake with gag magnate Marvin Acme. But when Acme turns up dead, Roger becomes the prime suspect, hunted by the terrifying Judge Doom (Christopher Lloyd) and his sinister Toon Patrol Weasels. Valiant, reluctantly, is Roger's only hope.

Bob Hoskins is simply magnificent as Eddie Valiant. Tasked with acting opposite characters who literally weren't there, relying on meticulously planned eyelines and physical cues, he grounds the entire fantastical premise in believable human weariness and eventual heroism. Hoskins reportedly had trouble shaking the role, even experiencing hallucinations of Toons for months after filming wrapped – a testament to the immersive (and perhaps mentally taxing) nature of the production. His performance is the hardboiled heart of the film, making the outrageous world feel tangible.

### More Than Just Jokes and Ink

While the film is bursting with slapstick energy and hilarious visual gags, writers Jeffrey Price and Peter S. Seaman (adapting Gary K. Wolf's darker novel Who Censored Roger Rabbit?) weave in surprisingly mature themes. There's the underlying commentary on prejudice (the segregation of Toons), corporate greed (Cloverleaf Industries' ominous freeway plot), and even temptation, embodied by the unforgettable Jessica Rabbit (voiced sultrily by Kathleen Turner, though uncredited, with Amy Irving providing her singing voice). Jessica's line, "I'm not bad, I'm just drawn that way," became instantly iconic, a perfect encapsulation of the film's playful subversion of expectations.

And then there's Christopher Lloyd as Judge Doom. Fresh from playing Doc Brown, Lloyd delivered a performance of pure, chilling menace. His cold, calculating presence is genuinely unnerving, building towards one of cinema's most nightmare-inducing reveals (Spoiler Alert! if you've somehow never seen it). The moment Doom reveals his true Toon nature, eyes bulging red, voice screeching high – fueled by the horrific "Dip" he created to execute Toons – is burned into the memory of anyone who saw it as a kid. It was proof that animation could be terrifyingly effective.

### The Miracle of Animation and Collaboration

Let's talk about the magic trick at the film's core. The integration of hand-drawn animation (led by the legendary animation director Richard Williams) with live-action footage was unprecedented in its complexity and execution. Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) handled the optical compositing, painstakingly adding shadows, highlights, and physical interactions that made the Toons feel truly present in the physical space. Actors rehearsed with rubber models and puppets, performers in creature suits, or sometimes just thin air, requiring immense concentration and imagination.

The budget ballooned to a then-staggering $50.6 million (around $130 million today), making it one of the most expensive films ever produced at the time. Disney executives were understandably nervous, but the gamble paid off handsomely, grossing nearly $330 million worldwide and revitalizing interest in theatrical animation. It snagged four Academy Awards, including a Special Achievement Award for Williams' animation direction and creation of the cartoon characters – a well-deserved nod to the groundbreaking work.

Perhaps just as astonishing was the diplomatic feat of getting rival studios' characters to appear together. Securing cameos from icons like Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Mickey Mouse, Goofy, Betty Boop, and dozens more required intricate negotiations, often stipulating equal screen time and dialogue for flagship characters like Mickey and Bugs. Seeing them interact is still a thrill, a piece of cinematic history that feels almost too good to be true.

### Retro Fun Facts

- Casting What-Ifs: Before Bob Hoskins landed the role of Eddie Valiant, numerous actors were considered, including Harrison Ford, Bill Murray, and Eddie Murphy. Imagine those versions!

- Deleted Darkness: An infamous deleted scene involved Eddie being given a literal pig's head by Judge Doom in Toontown, deemed too disturbing and cut before release. Fragments occasionally surface online, hinting at an even darker original vision.

- Practical Magic: Many "interactions" involved clever practical effects. Props were often manipulated by wires, rods, or puppeteers hidden just out of frame to simulate Toons handling objects. The attention to detail was immense.

- Jessica's Inspiration: Jessica Rabbit's design drew inspiration from various classic Hollywood starlets, including Rita Hayworth, Lauren Bacall, and Veronica Lake.

### The Verdict

Who Framed Roger Rabbit isn't just a movie; it's a landmark achievement. It's a dazzling fusion of genres – noir mystery, slapstick comedy, fantasy adventure – executed with technical brilliance and genuine heart. It respects its cartoon characters while placing them in a surprisingly adult, complex narrative. Rewatching it today, the effects largely hold up, a testament to the artistry involved, and the story remains as engaging and clever as ever. It perfectly captured that late-80s moment where filmmaking ambition felt limitless.

Rating: 10/10

This film earns a perfect score not just for its technical wizardry, which redefined what was possible in blending animation and live-action, but for its perfect storm of brilliant performances (Hoskins' grit, Lloyd's terror), sharp writing, Zemeckis' masterful direction, and its sheer, unadulterated imaginative power. It truly felt like the impossible made real.

For pure, unadulterated cinematic magic that bridged generations and studios, Who Framed Roger Rabbit remains a high-water mark, a treasured tape from the golden age of ambitious blockbusters. Pppppplease, Eddie? You won't regret revisiting this one.