He arrives like a mirage, shimmering out of the heat haze, a figure etched against the imposing Sierra Nevada landscape. The name's Preacher, but the collar feels almost like a disguise, perhaps even a cosmic joke. From its opening moments, Clint Eastwood's 1985 Western, Pale Rider, invites us not just to watch a story, but to ponder a presence – one that feels both achingly familiar from the annals of the genre and yet profoundly, unsettlingly mysterious. It was a welcome sight on video store shelves back then, a sign that the classic Western wasn't quite ready to ride off into the sunset.

Dust, Greed, and a Whisper of the Supernatural

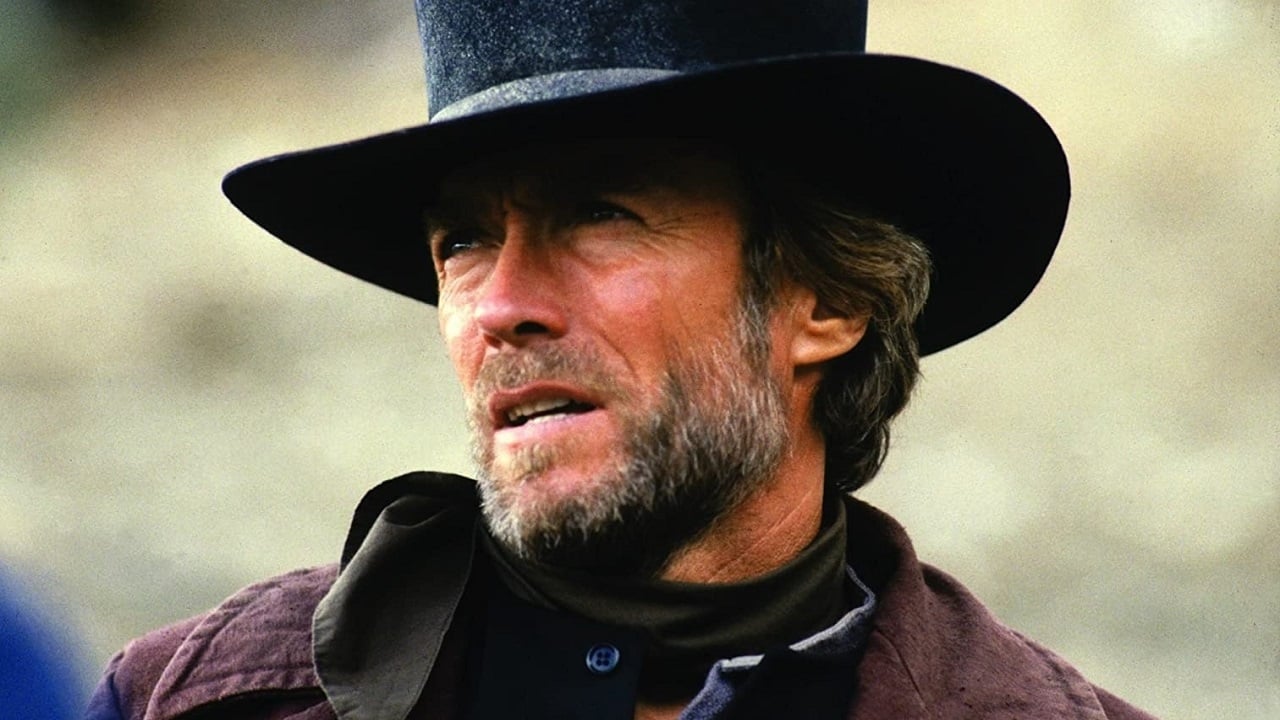

The setup is pure, distilled Western essence: a small community of independent gold prospectors ('tin pans') scratching a living in Carbon Canyon, relentlessly pressured by the ruthless industrial mining operation of Coy LaHood (Richard Dysart). LaHood’s methods are brutal, his ambition absolute, culminating in a violent raid that leaves the miners desperate. It’s young Megan Wheeler’s (Sydney Penny) heartfelt prayer for deliverance, spoken over a freshly dug grave, that seems to summon the lone rider. Is he merely a skilled gunslinger answering a call for help, or something more? The film masterfully walks this line. Eastwood, returning to direct and star in a Western for the first time since The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), doesn't give us easy answers. The Preacher carries the quiet authority we expect, but there's an otherworldly stillness to him, underscored by the prominent, almost ritualistically revealed bullet scars on his back. The title itself, drawn from the Book of Revelation ("And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death..."), hangs heavy in the air.

Echoes of the Past, Forged in the 80s

Watching Pale Rider again, decades after pulling that slightly worn VHS tape from its sleeve, what strikes me is how it feels both timeless and distinctly of its era. The core conflict – the little guy versus unchecked corporate power – resonates as strongly today as it did amidst the shifting economic tides of the mid-80s. Eastwood’s direction is lean and purposeful, much like his character. He lets the stunning Idaho locations (standing in for California) breathe, using the majestic, often harsh landscape captured beautifully by cinematographer Bruce Surtees as another character in the drama. There's a confidence here, a filmmaker fully in command of his craft and his signature genre.

Yet, it’s not simply a retread. While echoing the 'stranger comes to town' narrative seen in classics like Shane (1953) and even Eastwood’s own High Plains Drifter (1973), Pale Rider filters it through a slightly different lens. There's a cleaner, perhaps more polished look than the gritty revisionist Westerns of the 70s. The violence, when it erupts, is decisive and impactful, particularly in the climactic confrontation, but it lacks the raw, almost nihilistic edge of Drifter. Instead, the focus shifts towards that central enigma: the Preacher's true nature.

More Than Just a Man With No Name

Eastwood's performance is a masterclass in minimalist power. So much is conveyed through silence, a steely gaze, the slight tilt of his head. But the film wouldn't work nearly as well without the grounding presence of the supporting cast. Michael Moriarty, as Hull Barret, the de facto leader of the miners, is simply outstanding. He projects a vulnerability and quiet decency that makes him instantly sympathetic, providing the essential human counterpoint to the Preacher's mythic stature. His scenes with Carrie Snodgress as Sarah Wheeler, the woman he hopes to marry who finds herself drawn to the Preacher's quiet strength, carry genuine emotional weight. Their relationship, complicated by the stranger's arrival, adds a layer of adult drama that elevates the standard genre formula.

Let’s not forget the antagonists. LaHood might be a familiar greedy industrialist archetype, but Richard Dysart plays him with believable bluster. And then there's Marshal Stockburn, portrayed by Western veteran John Russell. His arrival with his six deputies, clad in distinctive dusters, is pure iconic imagery. Stockburn carries history with the Preacher, recognizing something terrifyingly familiar, adding another layer to the mystery and setting the stage for a truly memorable final showdown.

Retro Fun Facts: Behind the Dust

Pale Rider wasn't just a creative return for Eastwood; it was a significant commercial success, especially for a genre many considered past its prime in the 80s. Made for a relatively modest $6.9 million (around $19.7 million today), it pulled in over $41 million domestically (about $117 million adjusted for inflation), making it the highest-grossing Western of the decade for a time. This success arguably helped pave the way for other 80s/90s Western revivals like Young Guns (1988) and ultimately Eastwood’s own masterpiece, Unforgiven (1992). Interestingly, the script, credited to Michael Butler and Dennis Shryack, reportedly underwent significant changes by Eastwood himself, particularly emphasizing the ambiguous, possibly supernatural elements surrounding the Preacher.

The Lingering Shadow

Does Pale Rider reach the complex, deconstructive heights of Unforgiven? Perhaps not. Its narrative arc feels more traditional, its morality clearer, despite the central character's ambiguity. Some might find Megan's teenage infatuation with the Preacher a little awkward through a modern lens. Yet, the film's power endures. It’s a beautifully crafted, atmospheric Western that leans into the mythic elements of the genre with confidence and style. Eastwood delivers exactly what his audience wanted – the strong, silent hero taking down the bullies – but wraps it in layers of intrigue and spiritual questioning. What lingers most after the credits roll isn't just the satisfying action, but the haunting image of the Preacher, disappearing back into the landscape as enigmatically as he arrived. Did he even exist, or was he merely a manifestation of the miners' desperate hope?

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects a superbly executed, atmospheric, and iconic piece of 80s Western cinema. Eastwood is magnetic, the supporting cast is strong (especially Moriarty), and the direction is masterful. It successfully blends classic genre tropes with a compelling layer of mystery, making it more than just another revenge tale. While perhaps not as deep or revisionist as Eastwood's later Unforgiven, it stands as a significant and highly rewatchable entry in his directorial canon and a high point for the genre in its decade.

Pale Rider remains a potent reminder of Eastwood's unparalleled command over the Western, a ghost story wrapped in rawhide that still rides tall in the landscape of 80s film.