It wasn't just another year on the calendar; it was 1984. And as the actual year unfolded, marked by burgeoning pop optimism and brightly coloured tracksuits, a film emerged that felt like a deliberate, chilling counterpoint. Watching Michael Radford's adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four, particularly during its release year, felt less like viewing science fiction and more like peering through a distorted mirror reflecting anxieties simmering just beneath the surface of the Cold War era. There was an unsettling resonance then, a feeling that hasn't entirely faded with time. Slipping that tape into the VCR, you knew you weren't settling in for escapism.

### A World Washed Clean of Colour and Hope

From the opening frames, the film plunges you into a state of perpetual damp decay. This isn't the gleaming, high-tech dystopia often imagined; it's a world ground down, exhausted, perpetually grey. Much of this suffocating atmosphere is owed to the remarkable work of cinematographer Roger Deakins, then relatively early in his illustrious career. He employed a demanding bleach bypass process on the colour film stock, deliberately washing out hues to create a near-monochromatic palette dominated by sickly greens, grimy browns, and oppressive greys. It’s a visual choice that perfectly mirrors the Party’s systematic draining of life, individuality, and joy from Oceania. Filming occurred between April and June 1984, intentionally aligning with the dates specified in George Orwell's novel, adding another layer of eerie verisimilitude to the production, shot largely in rundown areas of London, including around the iconic Battersea Power Station which looms like a concrete behemoth.

### The Flicker of Humanity in John Hurt

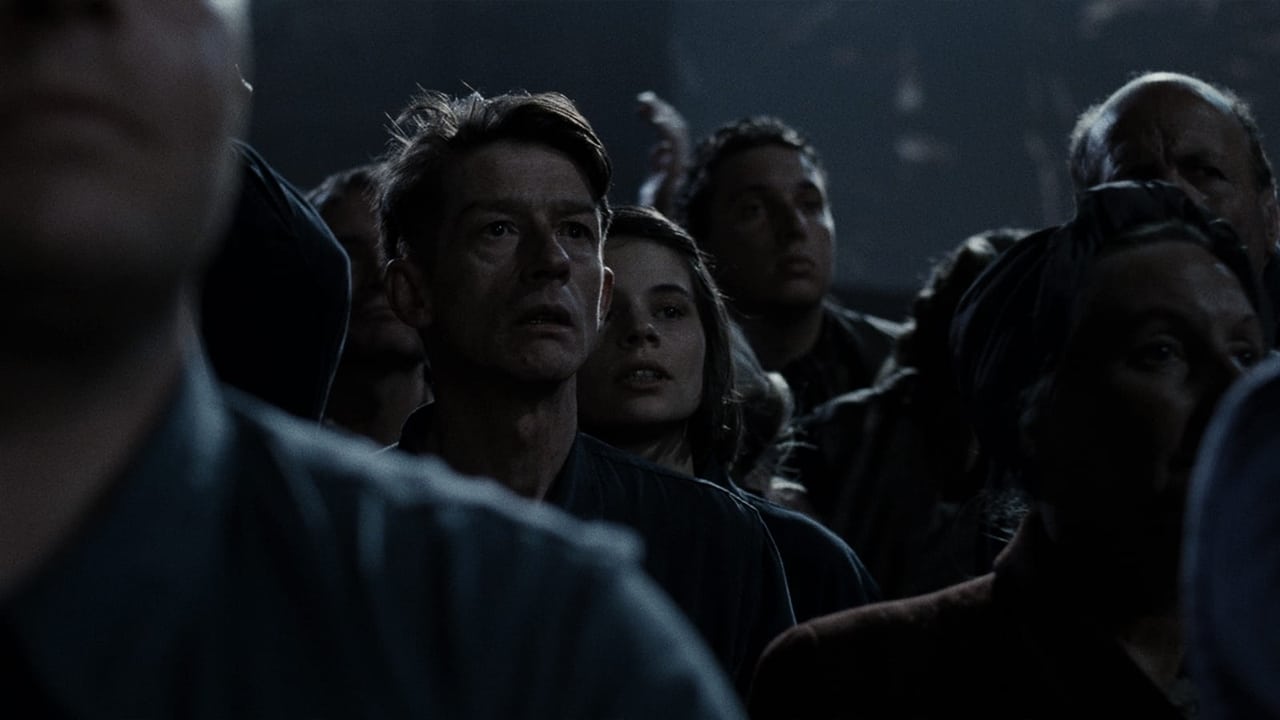

At the heart of this oppressive gloom is Winston Smith, embodied with weary perfection by John Hurt. Hurt, no stranger to bleak visions after his memorable turn in Alien (1979), doesn't play Winston as a hero itching for revolution, but as an ordinary man worn thin by omnipresent surveillance and psychological manipulation. His performance is a masterclass in suppressed emotion – the furtive glances, the tiny tightening around the eyes, the desperate act of writing in a forbidden diary. We see the crushing weight of the Party not through grand speeches, but through the exhaustion etched onto Hurt's face. His fragile hope, kindled by his illicit affair with Julia (Suzanna Hamilton, bringing a vital, albeit doomed, spark of rebellion), feels achingly real precisely because it seems so utterly futile against the monolithic state.

### The Chill of Unquestioned Authority: Richard Burton's Final Bow

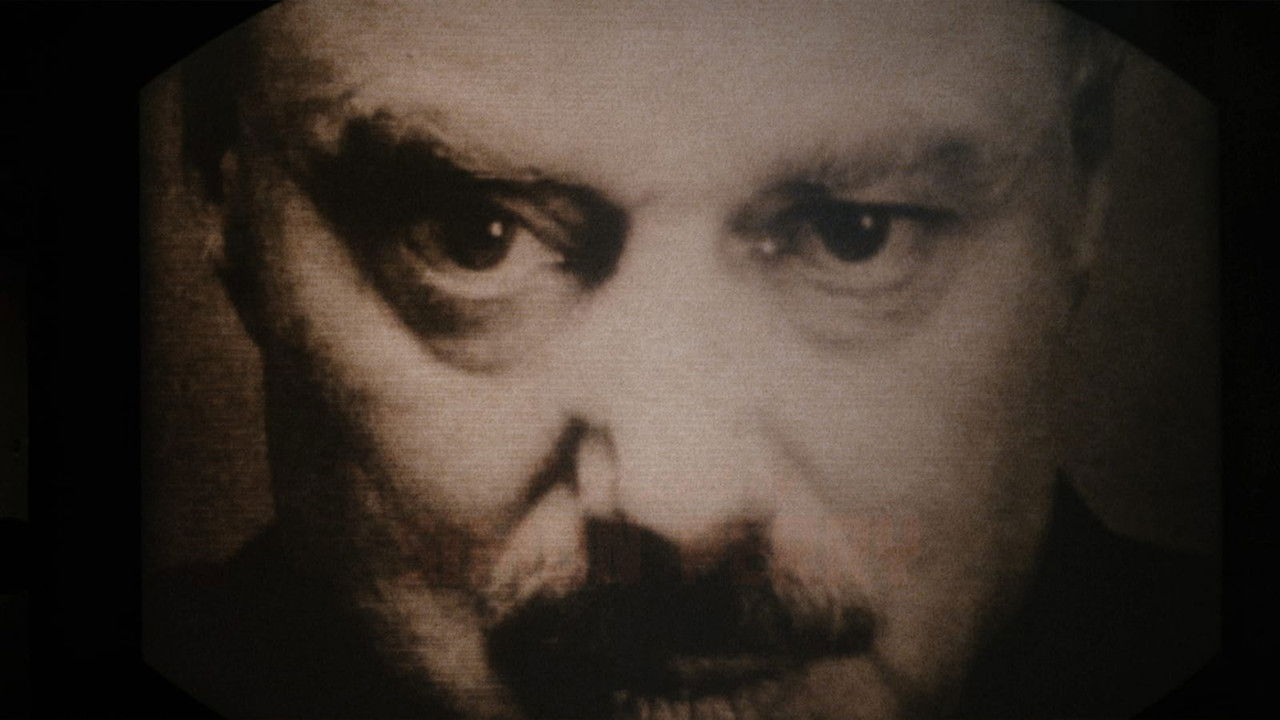

And then there is O'Brien. In his final screen role, Richard Burton delivers a performance of bone-chilling power. His O'Brien isn't a ranting megalomaniac; he is calm, intelligent, almost paternal in his cruelty. There's a weariness in him too, but it’s the weariness of absolute conviction in the Party's nihilistic ideology. The scenes between Hurt and Burton in the Ministry of Love, particularly in Room 101, are devastating. Burton, despite reportedly being in poor health during the shoot (he tragically passed away shortly after filming wrapped), commands the screen with an unnerving stillness. His quiet articulation of the Party's philosophy – the pursuit of power for its own sake, the denial of objective reality – is arguably more terrifying than any physical torture depicted. It's a towering final performance, imbued with a tragic weight that transcends the narrative.

### Behind the Iron Curtain of Production

The film's journey to the screen wasn't without its own struggles against powerful forces. Director Michael Radford, who also penned the adaptation, envisioned a specific bleak, orchestral score by Dominic Muldowney to complement the visuals. However, Virgin Films, the production company eager perhaps for wider appeal or a contemporary edge, commissioned and imposed a synth-pop score by Eurythmics. While some of the Eurythmics tracks undeniably capture a certain cold, electronic dread fitting the era, the conflict led to Radford feeling his artistic vision was compromised. Watching the film today, the moments featuring Muldowney's original cues often feel more organically woven into the oppressive fabric of the film, while the Eurythmics tracks sometimes feel like intrusions from the actual 1984 leaking into Orwell's nightmare vision. This soundtrack dispute became quite public, a fascinating footnote reflecting the perennial tension between artistic intent and commercial pressures. Made on a relatively modest budget (around £5.5 million), its box office ($8.4 million in the US) reflected its challenging nature – this was never destined to be a crowd-pleaser.

### Does Truth Still Matter?

What lingers most profoundly after watching Nineteen Eighty-Four isn't just the grim aesthetic or the powerful acting, but the questions it relentlessly forces upon us. In an age saturated with information, disinformation, and the constant curation of online personas, doesn't the Party's manipulation of history and language feel disturbingly relevant? Winston's desperate cling to the idea of objective truth ("Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four") resonates perhaps even more strongly now. The film avoids easy answers or catharsis. It offers a stark warning, rendered with artistic integrity and unwavering commitment to Orwell's vision. It’s a viewing experience that stays with you, leaving a cold residue of unease. I remember renting this tape, the stark cover art promising something intense, and it delivered – perhaps more than my teenage self was fully prepared for.

Rating: 9/10

Justification: This is a near-perfect adaptation, capturing the crushing atmosphere and thematic depth of Orwell's masterpiece with chilling precision. John Hurt and Richard Burton deliver career-defining performances, and Roger Deakins' innovative cinematography creates an unforgettable visual language. Its unflinching bleakness and the minor discordance of the imposed score prevent a perfect score, but its power and relevance are undeniable.

Final Thought: Decades after its release, and long after the year 1984 has passed, Radford's film remains a potent and deeply unsettling reminder: the greatest walls aren't always made of concrete, but of fear and the erosion of truth itself. A true heavyweight of the VHS era.