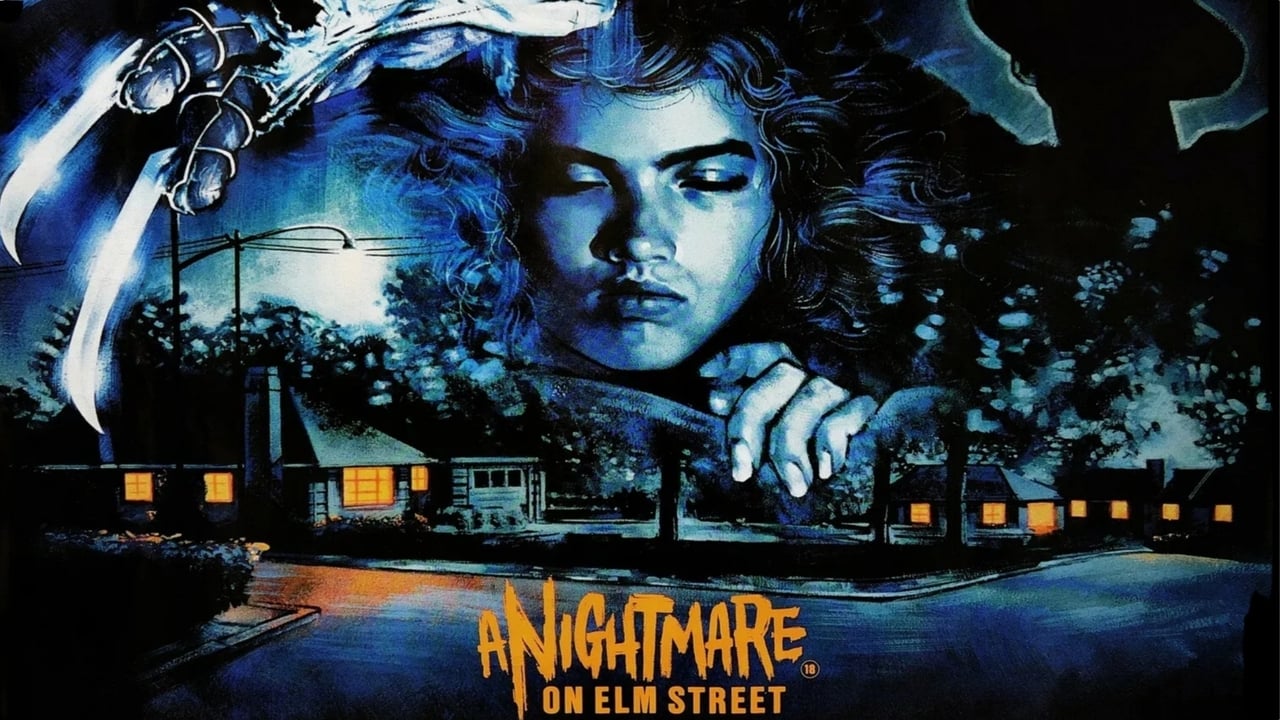

It began, as the most insidious nightmares often do, with a sliver of reality. Reports surfaced of young men, healthy one day, found dead the next, succumbing to horrors unseen in their sleep. Director Wes Craven, a filmmaker already adept at plumbing the depths of primal fear with films like The Last House on the Left (1972) and The Hills Have Eyes (1977), seized upon this unsettling mystery. From it, he didn't just craft a horror film; he birthed a modern myth, a boogeyman whose hunting ground was the one place we could never truly escape: our own minds. A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) wasn't just another slasher flick spilling onto Blockbuster shelves; it felt like a violation.

Where Sleep Offers No Sanctuary

The genius of Elm Street lies in its elegantly terrifying premise. Forget cabins in the woods or deserted summer camps; the threat here is woven into the fabric of adolescence itself – the exhaustion, the anxieties, the dawning realization that the adult world holds terrors far stranger than monsters under the bed. For Nancy Thompson (Heather Langenkamp) and her friends, sleep transforms from a refuge into a terrifying gauntlet ruled by a figure dredged from a shared, repressed past: Fred Krueger. The film masterfully builds a sense of suffocating dread, where the boundaries between the waking world and the dreamscape blur and eventually shatter. That haunting children's rhyme – "One, two, Freddy's coming for you..." – wasn't just creepy; it felt like a countdown whispered directly into your subconscious as the VCR whirred late at night. Doesn't that melody still send a faint shiver down your spine?

Forging an Icon of Fear

And then there's Freddy. Oh, Freddy. Before the sequels leaned into wisecracks and near-parody, the original Freddy Krueger, embodied with menacing physicality by Robert Englund, was pure, distilled nightmare fuel. Craven deliberately designed him to tap into subconscious fears: the dirty fedora pulled low, the obscuring shadows, that horrifyingly burnt visage. Fun fact: that iconic red-and-green sweater wasn't just a random choice. Craven had read an article claiming that specific color combination was one of the most difficult for the human eye to process simultaneously, creating a subconscious sense of unease. And the glove? Inspired by Craven observing a cat kneading its claws, fused with a primal fear of talons and sharp objects, it became an instant symbol of dread. Englund, initially not the frontrunner for the role (veteran actor David Warner was considered), brought a unique, almost balletic cruelty to Freddy's movements, making him more than just a hulking killer; he was a predator playing with his prey in their most vulnerable state.

Nancy Drew vs. The Nightmare Man

Standing against this force of nature is Nancy Thompson. Heather Langenkamp delivers a performance that grounds the film's surreal horror. She’s not just a damsel in distress; Nancy is intelligent, resourceful, and proactive. Watching her piece together the clues, confront the disbelief of the adults around her (a recurring theme in Craven's work), and ultimately decide to turn the tables on Freddy makes her one of the genre's most compelling "final girls." We root for Nancy not just because she's the protagonist, but because her terror feels authentic, her determination earned. Her journey from terrified victim to empowered dream warrior is the film's beating heart.

Practical Magic and Mayhem

What truly cemented A Nightmare on Elm Street's place in the VHS hall of fame were its astonishingly inventive and often terrifying practical effects. Working with a relatively modest budget (around $1.8 million – a pittance compared to its eventual box office haul which essentially built New Line Cinema, earning it the nickname "The House That Freddy Built"), the crew achieved miracles of nightmare logic. Who can forget Tina's (Amanda Wyss) body being dragged across the ceiling by an invisible force? Or Glen's (Johnny Depp in his feature film debut) explosive demise? That geyser of blood wasn't CGI, folks; it involved hundreds of gallons of fake blood and a purpose-built rotating room set that, legend has it, malfunctioned and spun the wrong way during one take, splattering gore absolutely everywhere. Even smaller moments, like the phone sprouting a tongue or Freddy pushing through the bedroom wall, have a tangible, unsettling quality that digital effects often struggle to replicate. These weren't just scares; they were surreal, often gruesome, works of art born from necessity and ingenuity. The battles with the MPAA over the intensity of these scenes were reportedly fierce, requiring several cuts to avoid an X rating.

Dream Logic, Enduring Terror

Wes Craven directed with a confidence that blended slasher tropes with surrealist horror, creating something genuinely unique. The film plays with perception, making the audience constantly question what's real and what's dream. The score by Charles Bernstein is instantly recognizable, its eerie synth notes perfectly complementing the on-screen dread. A Nightmare on Elm Street didn't just scare audiences; it burrowed into their psyche. It understood that the most effective horror often stems from the familiar twisted into the monstrous, and what's more familiar, more intimate, than our own dreams?

Its influence is undeniable, launching a massive franchise (of varying quality, let's be honest) and cementing Freddy Krueger as a horror icon alongside Michael Myers and Jason Voorhees. But revisiting the original, especially if you first experienced it on a grainy VHS tape rented from a local store, reminds you of its raw power. It was smart, scary, and unlike anything else out there.

VHS Heaven Rating: 9/10

This rating reflects the film's groundbreaking concept, its genuinely terrifying villain brought to life by Robert Englund, Heather Langenkamp's stellar performance, the astonishingly creative practical effects that still impress, and its lasting cultural impact. It’s a near-perfect execution of a high-concept horror idea that redefined the slasher genre in the 80s. Even now, decades later, the core idea retains its chilling power: what happens when sleep itself becomes the ultimate hunting ground? Sweet dreams... if you can manage them.