Some fears don't need ninety minutes to fester. They arrive in sharp, unnerving bursts, like static shocks in the dead of night. Remember those anthology horrors that felt like channel-surfing through someone's fractured psyche? 1983's Nightmares is precisely that kind of creature – a quartet of unsettling tales stitched together, leaving behind a lingering chill rather than a single, sustained scream. It’s the kind of tape you’d pick up based on the stark, evocative cover art alone, promising distinct flavours of dread packed onto one spool.

Flickering Fears, Uneven Dreams

Directed by the prolific Joseph Sargent (whose diverse credits range from the gritty realism of The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974) to the… well, less gritty Jaws: The Revenge (1987)), Nightmares has a fascinating, slightly fragmented origin story. It’s widely understood that these four segments were initially conceived as pilots for a prospective NBC horror anthology series, Darkroom, which ultimately didn't proceed beyond its initial run. Repackaged for theatrical release, this lineage perhaps explains the film's somewhat uneven feel – distinct episodes rather than a seamlessly woven tapestry. Yet, this very quality mirrors the experience of flipping through pulp horror magazines or catching disparate scary stories late at night, each leaving its own peculiar residue. The budget was a modest $5.5 million, and its $6.8 million box office return meant it wasn't a smash hit, cementing its status as more of a cult find than a mainstream memory for many.

Terror Runs on Unleaded

The first segment, "Terror in Topanga," plunges us into familiar territory: the urban legend. Cristina Raines (The Sentinel (1977)), chain-smoking her way through a late-night cigarette run despite news of an escaped killer, embodies a relatable, almost defiant vulnerability. The setup is pure campfire story – the isolated driver, the shadowy figures, the dawning realization of peril already inside the car. Sargent crafts genuine tension here, relying on atmosphere, tight framing within the claustrophobic car, and the power of suggestion over explicit gore. It’s simple, effective, and plays on primal fears of vulnerability and the dangers lurking just beyond the streetlight's glow. Doesn't that final reveal still pack a decent jolt, even knowing the trope?

High Score, High Stakes

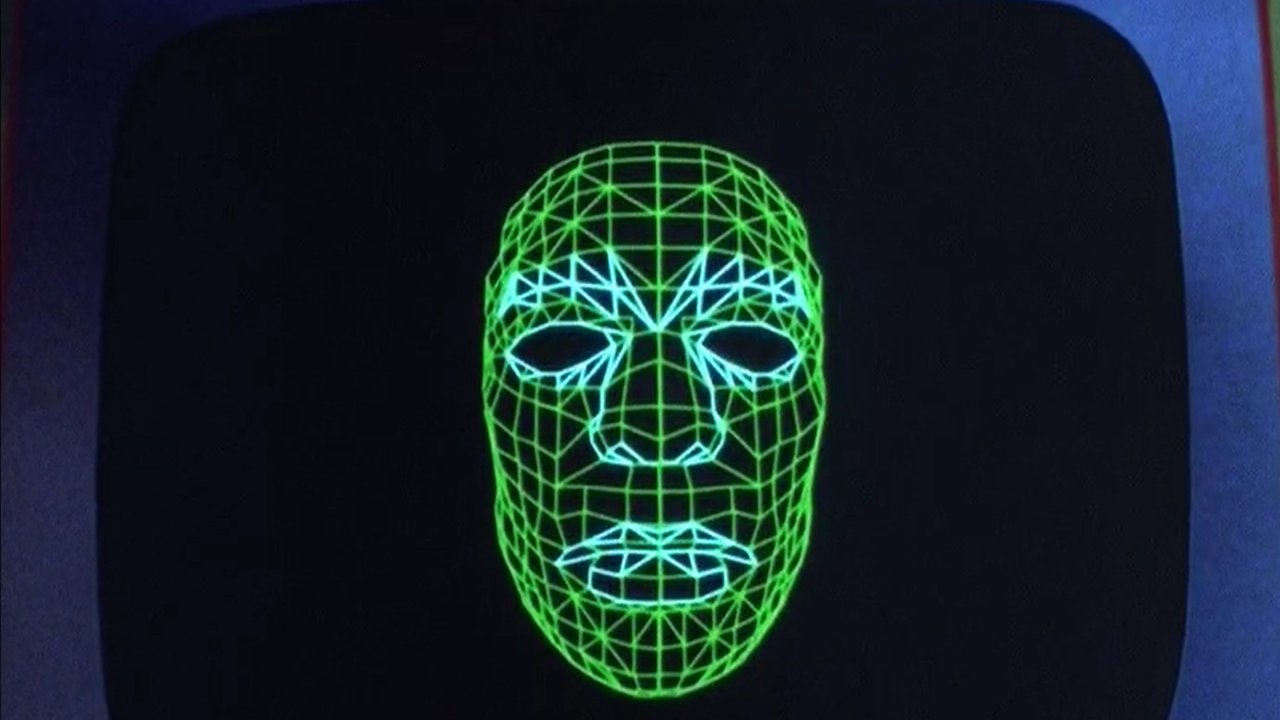

Then comes the segment that arguably burned itself into the retinas of a generation of arcade-goers: "The Bishop of Battle." Young Emilio Estevez, radiating punk energy and adolescent obsession, is J.J. Cooney, a kid hell-bent on conquering the notoriously difficult, almost mythical arcade game of the title. This chapter perfectly captures the buzzing, dimly lit intensity of early 80s video arcades – temples of blinking lights and digital dreams. The narrative escalates from teenage rivalry to something far stranger as the game itself begins to bleed into reality. The practical effects, merging rudimentary vector graphics with tangible, glowing adversaries emerging from the cabinet, were genuinely eye-popping back then. It's a fantastic time capsule of the era's anxieties about technology and obsession, culminating in a surreal, almost psychedelic showdown. Reportedly, the effects team faced significant challenges integrating the physical props with the animated game elements, a testament to the practical ingenuity required before digital compositing became commonplace. This segment alone often justified the rental fee back in the day.

Highway to Hell

"The Benediction" shifts gears dramatically, offering a slice of stark, supernatural dread. Lance Henriksen, bringing his signature intensity, plays a priest wrestling with a profound crisis of faith in a desolate desert town. After a tragic event shakes his belief, he hits the road, only to be pursued by a demonic, black pickup truck seemingly intent on his destruction. This segment drips with atmosphere – the vast, empty landscapes, the oppressive silence broken by the roar of an engine, Henriksen’s haunted performance. The truck itself, a hulking, malevolent presence with subtly unsettling modifications, is a fantastic piece of practical menace. It’s less about jump scares and more about existential terror and the feeling of being hunted by forces beyond comprehension. The choice of remote desert locations amplified the sense of isolation, making the priest's ordeal feel even more inescapable.

Something Scurrying in the Walls

Finally, "Night of the Rat" delivers a dose of good old-fashioned creature feature paranoia. Veronica Cartwright (a familiar face to sci-fi/horror fans from 1979's Alien), plays Claire, a suburban housewife increasingly terrified by a rodent infestation that proves to be far more than just a nuisance. As her pragmatic husband dismisses her fears, the evidence mounts, leading to a confrontation with an oversized, malevolent rat. This segment leans into B-movie territory, particularly with the reveal of the giant rat puppet. While perhaps the most dated segment effects-wise, there's a certain effectiveness to the claustrophobic domestic setting and the escalating sense of invasion. Working with the animatronic rat reportedly posed its own set of unique challenges, requiring clever camera angles and quick cuts to maximize its impact and conceal its limitations. It taps into that primal fear of vermin and the unsettling idea of your home being violated by something monstrous.

The Sum of Its Parts

Nightmares is undeniably a mixed bag, as anthologies often are. The segments vary in tone and effectiveness, lacking a strong connecting thread beyond their shared exploration of fear. Yet, viewed through the lens of VHS nostalgia, its appeal endures. It captures a specific flavour of early 80s horror – grounded in relatable anxieties but willing to veer into the bizarre and supernatural. The practical effects, even when dated, possess a tangible quality often missing today. It feels like a product of its time, a collection of dark fables discovered on a dusty video store shelf, perfect for a late-night viewing session where expectations are tempered, and the flickering glow of the CRT enhances the mood.

Rating: 6/10

Justification: Nightmares earns a solid 6 for its memorable segments, particularly the iconic "Bishop of Battle," and its effective capturing of different horror subgenres. While the anthology structure leads to unevenness and some segments feel underdeveloped or dated compared to others ("Night of the Rat" especially), the highs ("Bishop," "Benediction") are genuinely atmospheric and unsettling. Its origin as potential TV pilots explains some narrative thinness, but Joseph Sargent delivers moments of real tension and visual interest across the board. It lacks the cohesive brilliance of Creepshow (1982) but offers enough distinct chills and 80s flavour to remain a worthwhile slice of VHS-era horror history.

Final Thought: More than a collection of scares, Nightmares feels like flipping through unsettling snapshots of early 80s anxieties – technological obsession, urban legends, crises of faith, and the fear of what lurks just out of sight. A flawed but fascinating artifact from the golden age of video rentals.