Okay, pull up a chair, maybe crack open a cold one. Let's talk about a film that doesn’t quite fit comfortably on the shelf next to the high-noon shootouts and heroic posse rides. We're dropping the needle on Tom Horn, the 1980 Western that arrived like a cold gust of wind across the Wyoming plains, carrying with it the weight of a closing era, both on screen and, tragically, for its legendary star. This isn't your typical Saturday matinee fare; it's something quieter, bleaker, and altogether more haunting.

### A Chill in the Air

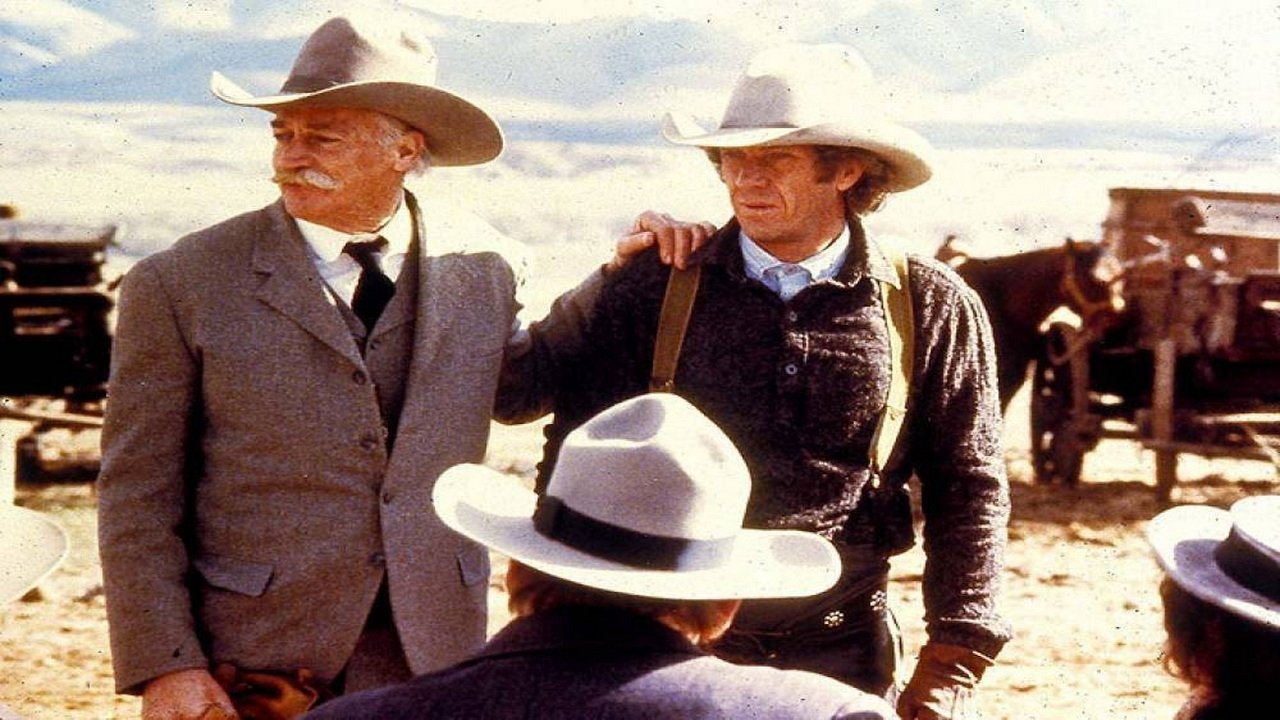

From the opening frames, captured with stark, often desolate beauty by cinematographer John Alonzo (who brought a very different kind of atmosphere to Chinatown), Tom Horn establishes a mood of profound unease. We meet Horn, played by Steve McQueen, not as a conquering hero, but as a man slightly out of time, adrift in a West that's rapidly fencing itself in, both literally and metaphorically. He’s a relic, a renowned tracker and former cavalry scout whose skills, once celebrated, are now becoming inconvenient, even dangerous, to the very cattle barons who hire him to deal with rustlers. There's an immediate sense of isolation, not just in the vast, unforgiving landscapes, but deep within the man himself.

### The Weight of McQueen

This film lives and breathes through Steve McQueen. By 1980, the 'King of Cool' persona was something he seemed eager to shed, or at least complicate. His Tom Horn is weathered, quiet, almost spectral. Gone is the easy charisma of Bullitt or the rebellious spark of The Great Escape. Instead, we see a man carrying the burden of his past, his face a map of hard miles and unspoken regrets. It’s a performance of remarkable restraint, relying on subtle glances, weary sighs, and a palpable sense of resignation. There’s an undeniable authenticity here, a feeling that McQueen tapped into something deeply personal.

Knowing the behind-the-scenes story adds another layer of poignancy. McQueen was fiercely passionate about bringing Horn’s story to the screen, so much so that he clashed with initial director James William Guercio (producer/manager for the band Chicago, and director of Electra Glide in Blue), leading to his replacement by TV veteran William Wiard. McQueen also had significant input on the script, working with writers Thomas McGuane (The Missouri Breaks) and Bud Shrake. He needed to tell this story. Tragically, McQueen was already battling the mesothelioma that would claim his life later that year. Watching him portray a man facing his own obsolescence and mortality, knowing his own time was short, lends the performance an almost unbearable weight. It’s impossible not to see the parallels, intended or not.

### Fading Legends and Fragile Connections

The supporting cast provides solid grounding. Richard Farnsworth, a former stuntman whose late-career renaissance was just beginning (he’d soon earn an Oscar nomination for The Grey Fox), brings a quiet dignity to John C. Coble, Horn’s rancher friend and employer, a man caught between loyalty and the changing tides of power. Linda Evans, pre-Dynasty fame, plays Glendolene Kimmel, the schoolteacher who offers Horn a fleeting glimpse of connection and warmth. Their scenes together have a gentle, fragile quality, though perhaps the romance feels somewhat secondary to Horn's inevitable collision course with 'progress'. It's a quiet counterpoint to the film's overarching bleakness.

### More Than Just Rustlers

Tom Horn isn't really about catching cattle thieves. It's about the brutal transition of the West from mythic frontier to settled territory, controlled by money and political influence. Horn represents the untamed spirit, the individual skilled in violence who becomes a liability once order is superficially imposed. The film deliberately muddies the waters regarding Horn’s guilt in the murder of a young boy – the crime for which he's ultimately tried and hanged. Was he framed? Was it a tragic mistake? Or did the lines simply blur for a man paid to dispense rough justice? The film doesn't offer easy answers, forcing us to confront the ambiguity. It’s a story drawn partly from Horn's own memoirs, written while awaiting execution, adding another layer to the legend vs. reality theme. It certainly stands in contrast to the more traditional, heroic portrayal seen in the 1979 TV movie Mr. Horn, which starred David Carradine.

### Production Echoes

The film's somewhat troubled production – the director change, McQueen's deep involvement, his failing health – arguably contributes to its slightly uneven feel at times. Some critics noted pacing issues or a lack of conventional narrative drive. Yet, these elements also mirror the film's themes: a world losing its certainty, a protagonist wrestling with forces beyond his control. Shot primarily on location in the stark landscapes of Arizona, the film reportedly cost around $3 million and earned a modest $9 million at the box office – a far cry from McQueen's earlier blockbusters, but perhaps fitting for such a somber tale. It wasn't designed to be a crowd-pleaser in the traditional sense.

### Final Verdict

Tom Horn might not be the first Steve McQueen movie you reach for on a Friday night. It lacks the visceral thrills of his action hits and the adventurous spirit of his earlier Westerns. But it possesses a quiet power and a haunting melancholy that lingers long after the credits roll. It’s a film about endings – the end of the Wild West, the end of a certain kind of man, and, unknowingly, nearing the end of a screen icon's life. McQueen's performance is a masterclass in understated intensity, a raw and vulnerable portrayal that feels deeply authentic. The atmosphere is thick with foreboding, and the film raises uncomfortable questions about justice, progress, and the price of clinging to the past.

Rating: 8/10 - The rating reflects the film's significant strengths, particularly McQueen's towering, deeply felt performance and its potent, elegiac atmosphere. While some pacing issues or underdeveloped subplots might slightly detract for some viewers, the film's thematic depth and haunting resonance make it a powerful and essential late-era Western, elevated by the tragic weight of its star's final turn in the genre he helped define.

It's a film that sits with you, a stark reminder that not all legends ride off into the sunset – some just fade into the cold, unforgiving landscape. A fittingly somber farewell from the King of Cool.