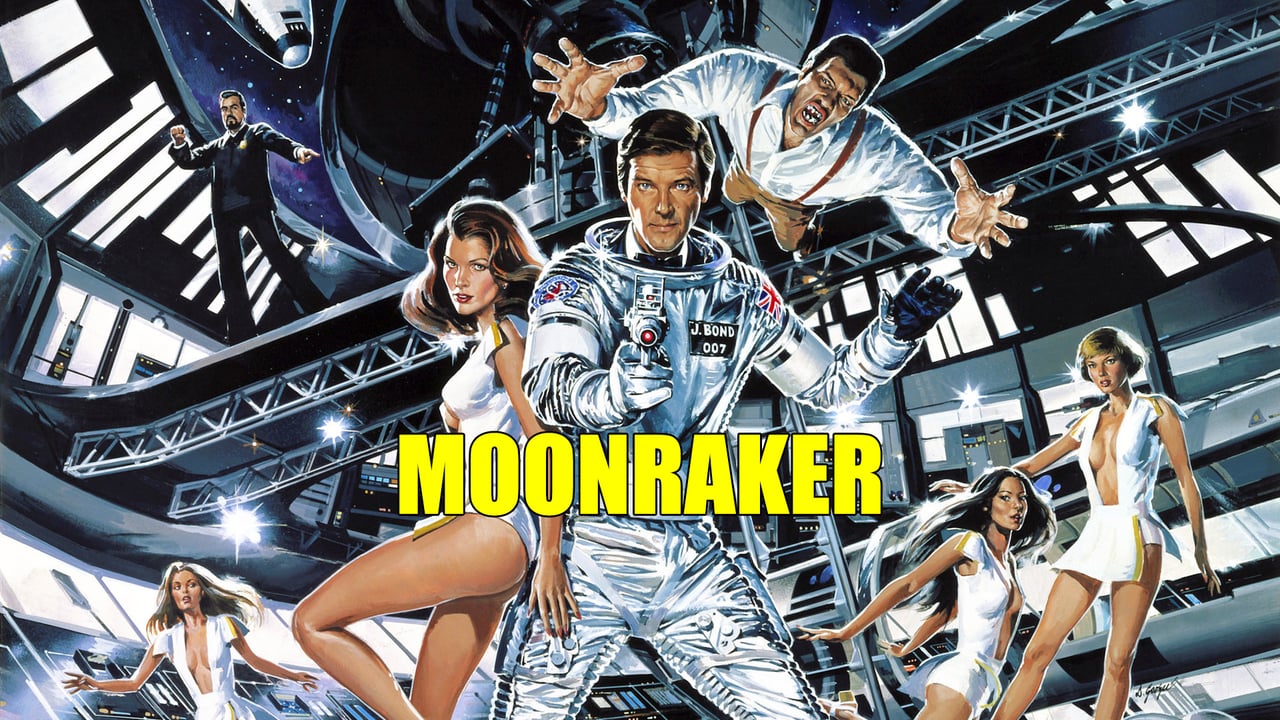

Alright, fellow tape travelers, let's rewind to a time when James Bond didn't just save the world, he saved it in space. Slide that worn copy of Moonraker into the VCR, adjust the tracking just so, and prepare for a blast-off of pure, unadulterated 1979 spectacle. Forget gritty realism; this was Eon Productions looking at the Star Wars phenomenon and saying, "Hold my vodka martini... and strap it to a rocket."

### From Venice with Love (and Hovercrafts)

Right from the iconic pre-credits sequence, Moonraker signals its intent: go bigger, go bolder, go absolutely bonkers. Bond (Roger Moore, hitting his stride in suave absurdity) gets shoved out of a plane without a parachute. What follows isn't CGI trickery, folks. This was terrifyingly real stunt work. Skydiver Jake Lombard actually performed the freefall, wrestling a chute off another jumper mid-air. Reportedly, it took an astonishing 88 jumps to capture those few minutes of heart-stopping footage, with a brave cameraman filming it all via a helmet rig. Remember how unbelievably tense that felt, watching it on a fuzzy CRT? That raw danger was palpable because it was real.

The film then whisks us off on a typically lavish Bondian tour: the canals of Venice, the vibrant chaos of Rio de Janeiro, the depths of the Amazon, and eventually... well, you know. Director Lewis Gilbert, returning after the similarly spectacular The Spy Who Loved Me, clearly understood the assignment: deliver escapism on an epic scale. In Venice, we get a gondola chase that suddenly involves Bond deploying... a hovercraft conversion. It's silly, it's audacious, and honestly, completely unforgettable. You can almost hear the producers saying, "How can we top the Lotus Esprit submarine? I know!"

### Drax, Jaws, and Jaw-Dropping Sets

Our villain is the magnificently calm and chilling Hugo Drax, played with understated menace by Michael Lonsdale. His plan? Wipe out humanity from orbit and repopulate with a master race bred in space. Standard billionaire stuff, really. Lonsdale delivers lines like "Look after Mr. Bond. See that some harm comes to him," with a delightful dryness that contrasts perfectly with the escalating madness around him. Fun fact: apparently, James Mason was considered for the role, but Lonsdale brings a unique Euro-cool villainy that fits the film's slightly detached tone.

Alongside Bond is CIA agent Dr. Holly Goodhead (Lois Chiles), a capable scientist who holds her own, even if the character name belongs firmly in the Moore era's playbook of double entendres. And who could forget the return of Jaws (Richard Kiel)? Fresh off his debut in The Spy Who Loved Me, the seemingly indestructible giant with the metal teeth gets some of the film's most memorable action beats, including that terrifying, vertigo-inducing fight atop the Sugarloaf Mountain cable cars in Rio. That sequence involved incredibly dangerous stunt work high above the ground, primarily performed by Richard Graydon (doubling Moore) and Martin Grace (doubling Kiel). Richard Kiel himself, a towering but gentle man, needed specially made, non-functional steel teeth props created by his dentist for the role – imagine wearing those all day!

The sheer scale of the production, masterminded by legendary designer Ken Adam, is breathtaking. Drax's Amazonian lair and his colossal space station are marvels of late-70s production design. These weren't digital creations; they were vast, physical sets built across enormous soundstages (some in France, partly to take advantage of their larger facilities and favourable tax conditions at the time). The film's budget ballooned to around $34 million – making it the most expensive Bond film ever produced up to that point. Adjusted for inflation, that's a serious chunk of change today, but it clearly paid off, grossing over $210 million worldwide and proving audiences were absolutely ready for Bond's cosmic adventure.

### Reaching for the Stars (Literally)

Okay, let's address the space-elephant in the room. The final act, featuring laser battles between US Space Marines and Drax's forces aboard his orbiting station, is where Moonraker fully embraces its sci-fi ambitions. Yes, it looks dated now. The zero-gravity effects rely heavily on obvious wirework, and the laser blasts have that charmingly simplistic animated quality. But think back to 1979. Seeing James Bond in a custom space suit, blasting away with a laser gun? It was mind-blowing! This wasn't the sleek, physics-conscious sci-fi we often see today; it was a comic book splash page brought to life using practical models, intricate compositing, and sheer filmmaking nerve. Composer John Barry’s lush score swells appropriately, anchoring the fantasy in that classic Bond sound, capped off by Shirley Bassey's powerhouse title theme – her record third for the franchise.

While critics were divided, with some finding the leap into space a step too far, audiences flocked to it. It became one of the highest-grossing films in the series, proving that sometimes, more is definitely more. It leans heavily into the campier side of Roger Moore's interpretation, full of quips and raised eyebrows, but it does so with such commitment and visual flair that it's hard not to get swept along for the ride.

***

VHS Heaven Rating: 7/10

Justification: Moonraker might be the Bond franchise at its most ludicrously excessive, but it delivers sheer, unadulterated spectacle like few other films of its era. The practical stunt work remains genuinely impressive (that opening freefall!), Ken Adam's production design is legendary, and the globetrotting adventure is pure escapist fun. It loses points for stretching the Bond formula to its absolute limit (and perhaps beyond) and for some effects that haven't aged gracefully, but its ambition and commitment to go-for-broke entertainment earn it a solid place in the pantheon of memorable, if divisive, 007 outings.

Final Thought: Forget subtlety; Moonraker is Bond blasting off into pure fantasy, fuelled by 70s excess and some truly daring practical filmmaking – a glorious, slightly goofy artifact from a time when aiming for the stars meant actually building the rocket.