It’s a strange thing to consider: a film likely seen by more people on Earth than Star Wars or Titanic, yet one that rarely flickers across the screens of mainstream retrospectives or cult film festivals. I’m talking about Jesus, the 1979 production spearheaded by The Genesis Project. Pulling this one from the metaphorical shelf doesn't feel quite like revisiting a blockbuster; it’s more like unearthing a cultural artifact, one many of us encountered not in multiplexes, but perhaps in church basements, school halls, or via a slightly worn VHS tape passed along with earnest conviction. It existed in a parallel distribution universe, a staple of religious outreach for decades, making its presence deeply felt throughout the 80s and 90s in a way few other films can claim.

Filming the Word

The ambition behind Jesus was staggering, not in terms of explosive set pieces or star power, but in its unwavering commitment to its source. Co-directed by Peter Sykes (who brought a certain gothic flair to Hammer films like Demons of the Mind) and John Krish (a respected documentarian), the film aims for a near-literal translation of the Gospel of Luke to the screen. Forget narrative embellishments or dramatic license; the screenplay by Barnet Bain adheres rigorously to the biblical text, often feeling less like a traditional biopic and more like a visual accompaniment to the scripture itself, underscored by the steady, authoritative narration of Alexander Scourby. This adherence is both its defining strength and, from a purely cinematic perspective, its potential limitation. It trades dramatic pacing for textual fidelity, creating an experience that feels earnest, educational, and profoundly sincere.

A Human Messiah

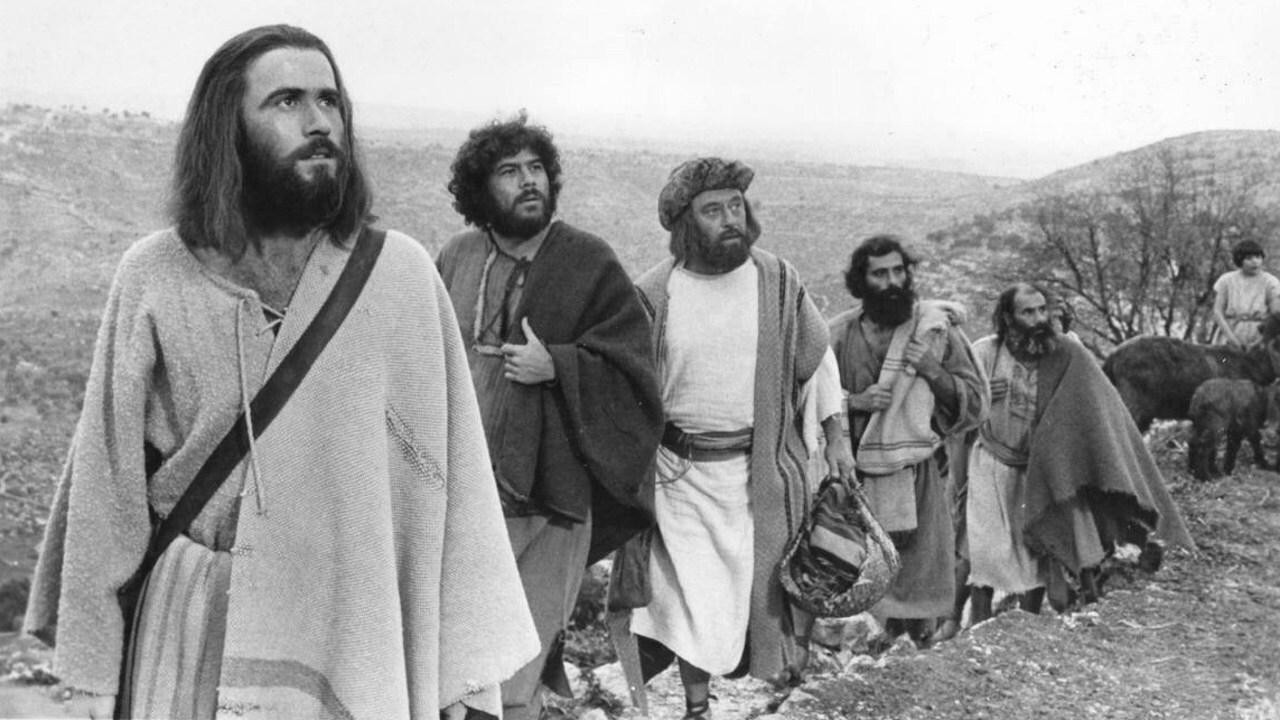

Central to the film's quiet power is the performance of Brian Deacon as Jesus. Reportedly chosen from hundreds of actors partly for his "ethnically correct" appearance and relative anonymity, Deacon portrays Christ with a grounded humanity. There’s little of the ethereal glow or booming pronouncements found in earlier epics. His Jesus is approachable, often smiling, his authority conveyed through quiet conviction rather than overt displays of divinity (though the miracles are depicted straightforwardly). It’s a performance that serves the film's purpose perfectly: presenting Jesus as relatable, a figure one could imagine walking and talking with on the dusty roads of Galilee. Supporting players like Rivka Neuman as Mary offer solid, if brief, contributions, but the focus remains resolutely on Deacon and the narrative path laid out by Luke. Watching it again, Deacon's performance feels remarkably restrained and effective within the film's specific constraints.

Authenticity on a Budget

Shot entirely on location in Israel, the production aimed for a high degree of historical and cultural accuracy for its time. The costumes, sets, and depiction of daily life strive for an authentic feel, avoiding the polished Hollywood sheen often seen in biblical epics. This quasi-documentary approach lends the film a unique texture. It feels less like a spectacle and more like an attempt to witness events as they might have unfolded. While some aspects inevitably feel dated now, the commitment to this grounded realism is palpable and contributes significantly to the film's enduring appeal for its intended audience. There's a certain charm to its practical, unadorned presentation, a far cry from the CGI-heavy interpretations that would follow decades later.

The VHS Phenomenon

For many readers of "VHS Heaven," the memory of Jesus is likely tied directly to the clunky plastic cassette. This wasn't typically a movie you rented from Blockbuster on a Friday night. Its distribution, largely through Campus Crusade for Christ (now Cru) and the resulting "Jesus Film Project," was a groundbreaking phenomenon in itself. The goal was translation and dissemination on an unprecedented scale. The fact that it holds the Guinness World Record for the most translated film in history (into over 2,000 languages as of recent counts) speaks volumes about its reach. Seeing that slightly fuzzy, perhaps pan-and-scan version on a CRT TV became a shared experience for millions globally, completely bypassing conventional distribution channels. It’s a potent reminder of how VHS technology enabled niche content – in this case, faith-based – to find vast audiences far beyond the cinema.

Legacy Beyond the Screen

Evaluating Jesus purely as a piece of cinema is complex. It wasn't made to compete with Hollywood dramas; it was crafted as a tool for evangelism and education. Judged by its own intentions – to present the life and ministry of Jesus according to Luke accurately and accessibly – it is remarkably successful. Its straightforward narrative, Deacon's humanizing portrayal, and the sheer scale of its global distribution make it a unique landmark. Does it offer the complex character interpretations or dazzling cinematic techniques of other films? Perhaps not. But its power lies in its simplicity, its sincerity, and its unparalleled reach. It aimed to translate a specific text into a visual medium for the widest possible audience, and in that, its success is undeniable.

Rating: 7/10

The rating reflects the film's effectiveness in achieving its specific, monumental goals, Brian Deacon's earnest performance, and its unique cultural footprint via initiatives like The Jesus Film Project, particularly during the VHS era. While perhaps lacking the dramatic flair or cinematic innovation of other religious epics, its fidelity to the source material and unprecedented global reach make it significant. It stands apart, less a movie in the conventional sense, and more a filmed gospel intended for the world.

What lingers after watching Jesus again isn't necessarily cinematic artistry, but the sheer, quiet conviction behind its creation and the extraordinary journey that followed, carrying its message across languages and continents, often housed within the humble shell of a VHS tape.