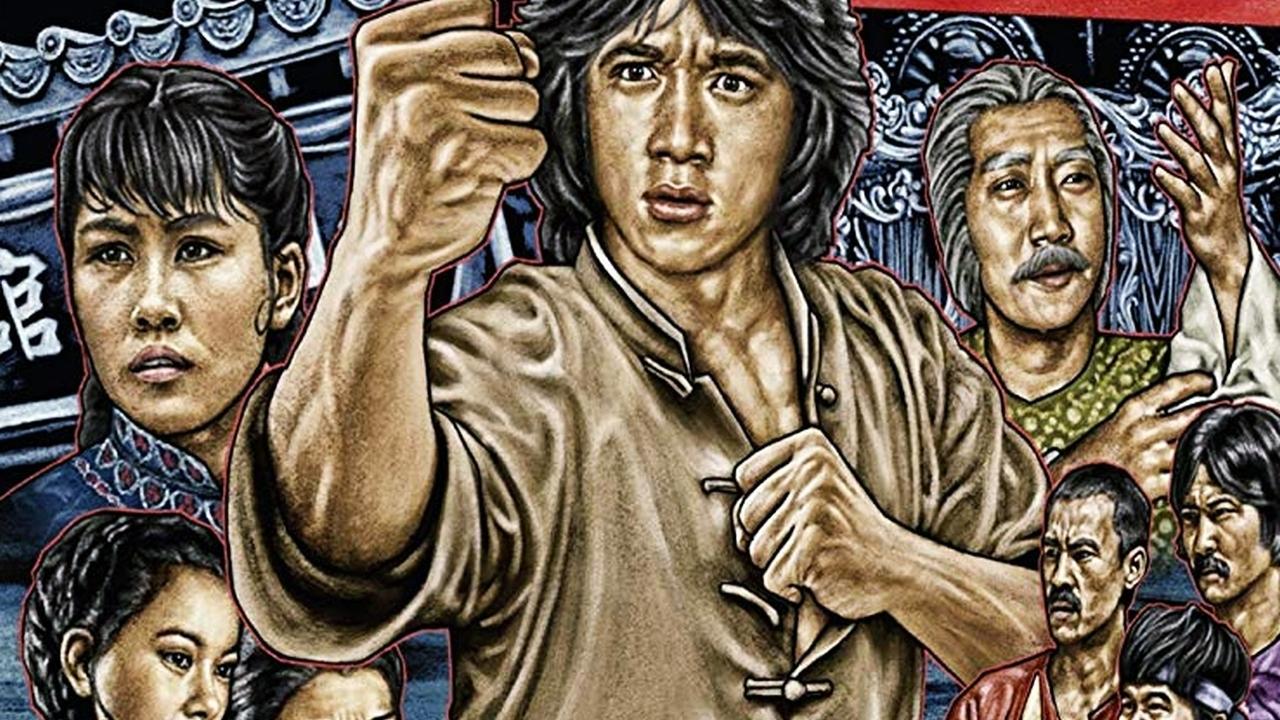

Okay, pop that tape in, ignore the tracking lines for a second, and let’s talk about a fascinating, slightly awkward corner of the Jackie Chan cinematic universe: Dragon Fist (1979). This wasn't the smiling, prop-wielding Jackie many discovered later. Released right after his star-making turns in Snake in the Eagle's Shadow and Drunken Master blew the doors off Hong Kong cinema, Dragon Fist feels like a throwback, a glimpse of the star Lo Wei thought he was building. And you know what? It’s a compelling, sometimes brutal watch, especially when viewed through that flickering CRT glow.

### Before the Laughter, There Was Fury

The first thing that hits you about Dragon Fist is its tone. It’s serious. Forget the intricate physical comedy; this is straight-up revenge-fueled martial arts melodrama. Jackie Chan plays Tang How-Yuen, a disciple whose master is killed in a sneak attack by the ruthless Chung Chien-Kuen (played with sneering menace by Yen Shi-Kwan). Tang, along with his master’s widow (the great Nora Miao, a frequent co-star of Bruce Lee) and daughter, seeks justice, leading them into a web of betrayal and simmering resentment in a new town.

Here's a crucial bit of retro fun fact context: Dragon Fist was actually filmed before Chan hit superstardom with his Seasonal Films collaborations under Yuen Woo-ping. Director and producer Lo Wei, who had Chan under a tight contract, was still trying desperately to mold him into the next Bruce Lee – intense, brooding, lethal. When Snake and Drunken Master exploded at the box office in 1978, Lo Wei rushed to release his backlog of Chan films, including this one, to cash in. This explains why Dragon Fist feels stylistically different from the films that immediately preceded its release date; it represents an earlier, more constrained phase of Chan's career development. You can almost feel Chan straining against the dramatic confines, itching to inject more of his unique personality.

### Raw Power, Practical Pain

Let’s talk about the action, because that’s why we kept renting these tapes, right? While Lo Wei’s direction can feel a bit stiff compared to the dynamism Chan would later achieve directing himself or working with collaborators like Sammo Hung, the fight choreography here has a raw, impactful quality. This is classic late-70s Hong Kong stunt work – fast, intricate, and undeniably physical.

Remember how real those hits looked back then? No CGI wire removal, no digital touch-ups. When someone gets slammed into a wall or takes a flying kick, you feel the jolt. Jackie Chan is already showcasing his incredible athleticism and timing, even if the scenarios aren't as wildly inventive as his later work. The weapon fights, particularly involving staffs and swords, are sharp and well-executed. The final confrontation is a highlight – a lengthy, punishing battle that really showcases Chan’s endurance and burgeoning screen presence. It lacks the playfulness of his peak work, but substitutes it with a certain grounded ferocity that was common in the genre at the time. It’s a reminder of an era where stunt performers genuinely put their bodies on the line with fewer safety nets, delivering thrills that felt visceral and immediate.

### More Than Just Jackie

While Chan is the undeniable draw, the supporting cast adds weight. Nora Miao brings a quiet dignity and resolve to her role as the grieving widow, providing the film's emotional anchor. James Tien, a reliable face in Hong Kong cinema (often seen alongside both Bruce Lee and later Jackie Chan), plays Fang Kang, a man caught in the middle, delivering a nuanced performance that adds complexity to the plot. The villain, Yen Shi-Kwan, is effectively hateable, providing a solid antagonist for Chan's righteous quest.

Lo Wei, despite his somewhat rigid directorial style here compared to his earlier Bruce Lee hits like The Big Boss (1971) and Fist of Fury (1972), still knew how to stage a traditional martial arts narrative. The plot, while relying on familiar tropes of revenge and hidden identities, moves along serviceably, punctuated by those all-important action set pieces. The film reportedly had a decent budget for its time, allowing for some evocative period sets and costumes that lend authenticity to the story.

### A Stepping Stone, Not a Destination

Watching Dragon Fist today is like looking at an early photograph of a superstar. You see the potential, the raw talent, the physical gifts. But you also see the constraints – the attempt to fit Chan into a pre-existing mold, the dramatic beats that feel a touch heavy-handed now. It wasn't a massive hit like Drunken Master, nor did it redefine Chan's image. Instead, it served as a potent, if slightly somber, reminder of his contractual obligations to Lo Wei just as his own creative star was ascending. I remember finding this on a dusty shelf at the local video store, probably in a slightly battered box, expecting the usual Jackie laughs and instead getting this surprisingly grim tale. It was jarring, but the action still delivered that late-night viewing thrill.

Rating: 6.5 / 10

Justification: Dragon Fist earns its points for showcasing Jackie Chan's early, powerful martial arts skills in a series of well-executed, grounded fight scenes. The presence of Nora Miao adds class, and the film serves as a fascinating historical document of Chan's career transition under Lo Wei. However, it loses points for the somewhat dated melodrama, Lo Wei's occasionally static direction, and the overall feeling that Chan's unique comedic and acrobatic talents are being held back. It's good, sometimes even great in its action moments, but lacks the sheer inventiveness and joy of his subsequent peak work.

Final Thought: Before the blooper reels, there was the burn – Dragon Fist is a potent shot of 70s kung fu seriousness, a necessary, sometimes painful step on Jackie Chan's journey to becoming the legend we know and love. Worth seeking out for a glimpse of the legend finding his footing, fists first.