It starts with the hands. One moment, they caress the keys of a piano, coaxing out the intricate architecture of a Bach fugue; the next, they’re instruments of brutal enforcement, collecting debts for a loan shark father. This jarring duality isn't just a plot point in James Toback's directorial debut, Fingers (1978); it's the fractured soul of the film itself, a raw, unsettling exploration of a man caught between artistic aspiration and violent inheritance. Watching it again, decades after first encountering its unsettling energy on a worn VHS tape, the film feels less like a straightforward narrative and more like a prolonged, waking fever dream set on the grimy streets of late-70s New York.

A City's Jagged Pulse

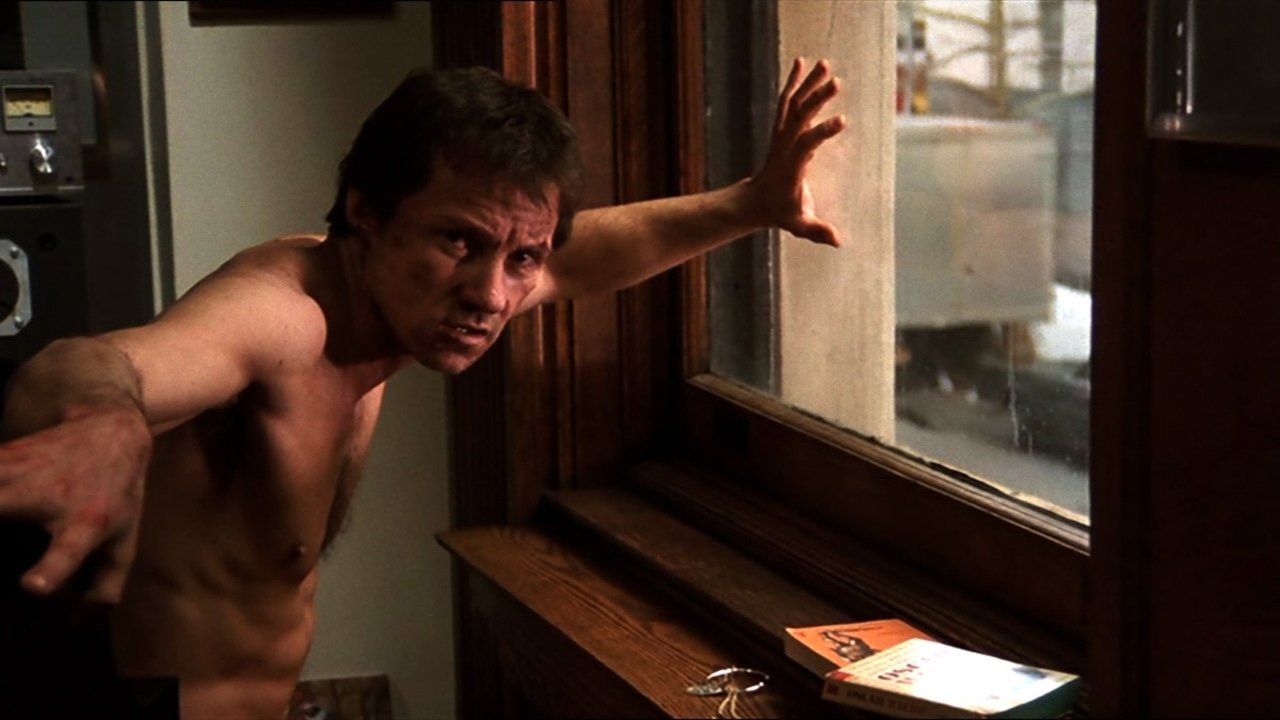

Toback, who also penned the script, plunges us headfirst into the world of Jimmy "Fingers" Angelelli. There's no gentle introduction, no easing into his chaotic existence. We're immediately confronted with his contradictions: the sensitive musician yearning for Carnegie Hall recognition and the volatile enforcer capable of sudden, shocking violence. The New York captured here isn't the romanticized version; it's dirty, dangerous, and pulsing with a nervous energy that perfectly mirrors Jimmy's internal state. The cinematography feels appropriately restless, often favouring uncomfortable close-ups that trap us within Jimmy's volatile headspace. It’s a film that feels less constructed and more excavated, dug out from the anxieties of its time and place.

Keitel: A Portrait in Raw Nerves

At the absolute centre, holding this fragmented world together, is Harvey Keitel. This isn't just a performance; it's an act of exposure. Keitel embodies Jimmy with a frightening intensity, veering wildly between moments of quiet introspection at the piano and explosions of terrifying rage. He makes Jimmy’s internal war palpable – the desire for transcendence through music constantly undercut by the gravitational pull of his father's world and his own barely contained impulses. It's a performance devoid of vanity, often uncomfortable to watch, yet utterly compelling. You see the flicker of hope in his eyes when he talks about his audition, only for it to be extinguished by the deadening weight of his obligations. James Toback reportedly drew heavily on his own experiences with gambling and obsessive behaviour, channeling them into the script, and Keitel seems to have tapped directly into that raw, autobiographical nerve. Trivia buffs might know Keitel, despite not being a pianist, worked diligently to make his playing look authentic, focusing on the physicality and passion required for Bach's demanding pieces – a commitment visible in every frame he spends at the keyboard.

Worlds Colliding

The narrative, such as it is, follows Jimmy's increasingly desperate attempts to reconcile his two lives. His father, Ben (Michael V. Gazzo, unforgettable from The Godfather Part II), represents the suffocating pull of the past and the streets. His potential escape route lies through Carol (Tisa Farrow, Mia's sister, bringing an ethereal, almost detached quality), a spacey artist who seems to exist in a different reality altogether, and his potential music manager, Dreems (Jim Brown, the legendary NFL star projecting sheer physical intimidation), a powerful figure straddling the legitimate and criminal worlds. The interactions are often jarring, reflecting Jimmy's own disjointed experience. Scenes don't always flow conventionally; sometimes they collide, mirroring the character's inability to integrate the disparate parts of his life. Is Carol a genuine connection, or just another manifestation of Jimmy's fractured psyche? The film leaves these questions hanging, preferring ambiguity over easy answers.

Retro Fun Facts & Lingering Dissonance

Fingers was made on a relatively low budget (estimated around $900,000), and that rawness contributes significantly to its authentic, street-level feel. It wasn't a box office smash upon release, earning mixed reviews, but its uncompromising nature and Keitel's powerhouse performance secured its cult status over the years, particularly among cinephiles who discovered it later on home video – a true gritty 70s crime drama VHS find. Its influence resonated, notably inspiring the acclaimed 2005 French remake The Beat That My Heart Skipped, directed by Jacques Audiard. Toback's insistence on shooting on location in some rough New York neighbourhoods adds a layer of verisimilitude that studio sets could never replicate. The juxtaposition of high art (Bach) with low-life crime wasn't just thematic; it was structural, creating a constant, unsettling tension. Remembering pulling this tape off the shelf back in the day… it was definitely not the kind of crime film you casually popped in for easy entertainment. It demanded your attention, burrowed under your skin.

What lingers most after the screen fades to black isn't a neat resolution, but a feeling of profound unease. Fingers doesn't offer easy answers about nature versus nurture, or the possibility of escaping one's background. It presents a character study so intense, so stripped bare, that it borders on the primal. It asks uncomfortable questions about masculinity, violence, and the often-unbridgeable gap between who we are and who we aspire to be. Doesn't Jimmy's struggle, in its extremity, echo the quieter battles many fight against their own ingrained patterns or inherited burdens?

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's undeniable power and Keitel's towering performance, balanced against its deliberately abrasive and sometimes uneven nature. It's not an easy watch, and its pacing can feel erratic, but its raw honesty and psychological depth are unforgettable. Fingers stands as a unique, challenging piece of 70s American cinema, a testament to James Toback's singular vision and Harvey Keitel's fearless commitment. It’s a film that gets under your skin and stays there, like a dissonant chord that refuses to resolve.