It often begins with a question, doesn't it? A nagging curiosity that burrows under the skin. For Al Pacino, a titan known more readily for navigating the treacherous streets of cinematic crime than the hallowed halls of Elizabethan theatre, the question was Shakespeare. Specifically, Richard III – that magnetic, monstrous vortex of ambition and evil. How could he bridge the perceived gap between the Bard and the modern American audience, the folks on the street who might shrug and say, "It's got nothing to do with me"? 1996’s Looking for Richard isn't just a film; it's the chronicle of that intensely personal, surprisingly raw quest.

More Than Just a Documentary

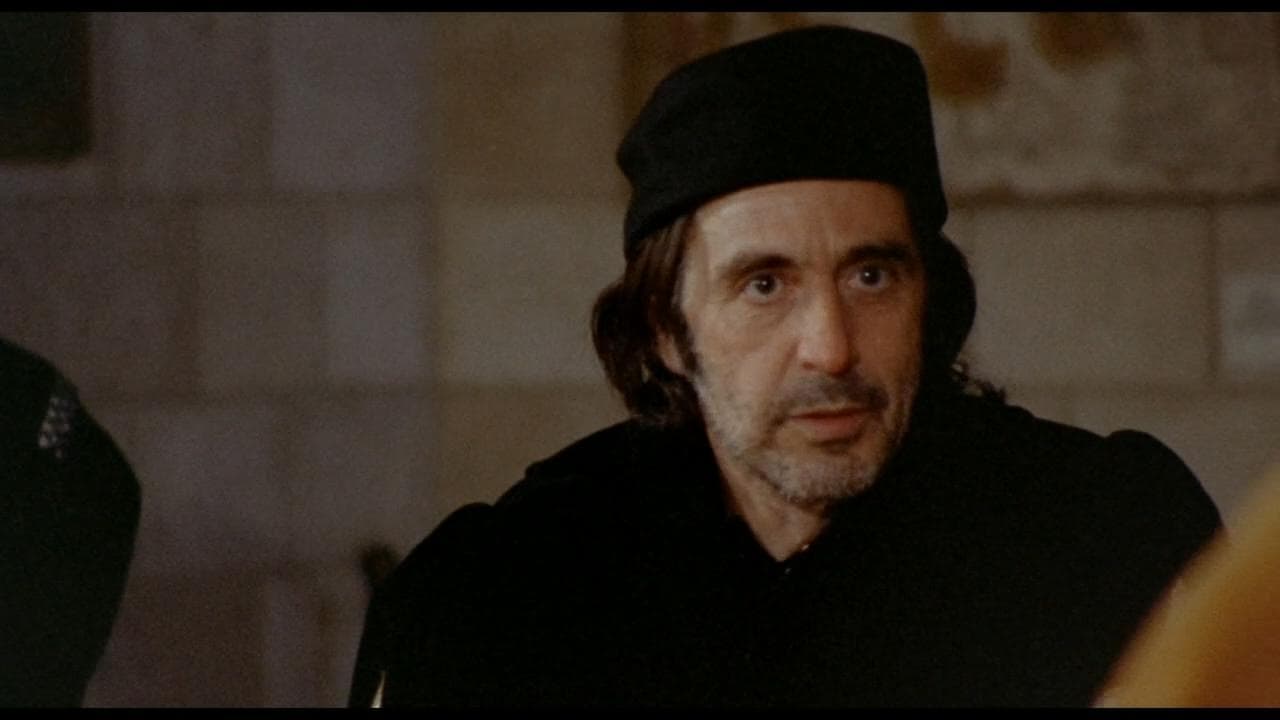

Forget any notion of a stuffy, academic lecture. Pacino, directing himself and a frankly astonishing ensemble cast, throws the conventional documentary format out the window. What emerges is a vibrant, sometimes chaotic, utterly captivating hybrid. It’s part rehearsal footage, part performance snippets, part historical investigation, part philosophical musing, and crucially, part street-level vox pop. Pacino, playing a version of himself – passionate, obsessive, charmingly exasperated – is our guide, dragging us along on his mission to unlock the power and relevance of Richard III. The energy is palpable, feeling less like a polished film and more like being invited into Pacino's whirlwind process. It's a film that feels like the 90s indie scene – raw, immediate, and driven by a singular vision, a stark contrast to the slicker studio fare dominating the multiplexes back then.

Pacino's White Whale

This wasn't some casual whim. Looking for Richard was the culmination of decades of fascination for Pacino, who had wrestled with the role of Richard on stage. The film itself reportedly took years to complete, stitched together as Pacino found time and funding between his higher-profile acting gigs. You can feel that long-term investment; it permeates every frame. His goal wasn't just to perform Richard, but to dissect him, understand him, and crucially, communicate why this 400-year-old character still matters. He brings his trademark intensity, but it's channeled not into explosive rage, but into fervent intellectual and emotional exploration. There's a vulnerability here, seeing Pacino grapple with the text, consult scholars, and push his actors, all in service of demystifying Shakespeare. It cost a reported $1.5 million, a passion project funded largely by Pacino himself, and while it wasn't a box office smash ($1.3 million gross), its value lies far beyond dollars.

An Actor's Roundtable

Pacino surrounded himself with talent, a mix of screen stars and seasoned stage actors. Watching Alec Baldwin work through the nuances of Clarence, or a young Winona Ryder explore the complexities of Lady Anne under Pacino’s direction, is fascinating. Kevin Spacey, as the calculating Buckingham, offers a particularly sharp counterpoint to Pacino's Richard – their scenes together crackle with intelligence and veiled threat, showcasing Spacey's formidable talent before his later fall from grace. We also get insights from theatre legends like Estelle Parsons and Penelope Allen, alongside brief but illuminating interviews with figures like Kenneth Branagh and John Gielgud (in one of his final appearances), adding layers of expertise and perspective. The film becomes a masterclass not just in Shakespeare, but in the collaborative, often messy, process of acting itself. Seeing these familiar faces grapple with the language, finding the modern pulse within the verse, is a treat. Remember seeing Ryder, fresh off films like Reality Bites, tackling Lady Anne? It felt like a bold, unexpected move, typical of the film's surprising energy.

Breaking Down the Bard

Where Looking for Richard truly shines is in its accessibility. Pacino and his co-writer Frederic Kimball aren't afraid to stop the action, explain plot points, discuss motivations, or provide historical context. They intercut scenes performed in costume (often in evocative locations like The Cloisters in New York City) with spirited discussions amongst the actors and scholars. The famous opening monologue ("Now is the winter of our discontent...") is workshopped, debated, and explored from multiple angles. It never feels condescending; rather, it feels like an invitation. Pacino seems to be saying, "Look, this stuff might seem intimidating, but let's figure it out together." The man-on-the-street interviews, while occasionally jarring, serve a clear purpose: they ground the lofty text in everyday reality, highlighting the communication gap Pacino is determined to close. Do these moments always land perfectly? Perhaps not, but their inclusion speaks volumes about the film's democratic spirit.

A Lasting Impression

Does Looking for Richard succeed? Absolutely. It doesn't just present Shakespeare; it interrogates the experience of encountering Shakespeare. It makes the case, persuasively and passionately, for the enduring power of these stories and this language. For those of us browsing the video store shelves in the mid-90s, stumbling upon this tape might have been a revelation – expecting maybe a straightforward performance film, and instead finding this dynamic, personal exploration. It stands as a unique entry in Pacino’s filmography, a testament to his artistic curiosity beyond the roles that made him a screen icon. Watching it today, it feels like a time capsule – not just of 90s filmmaking sensibilities, but of a moment where a major star used his clout to champion something deeply personal and potentially uncommercial. It reminds us that great art isn't meant to be kept under glass; it's meant to be wrestled with, argued over, and ultimately, felt.

Rating: 8/10

Looking for Richard is a passionate, intelligent, and deeply engaging exploration of Shakespeare, acting, and the challenge of making classic art resonate today. Its unconventional structure and Pacino's infectious energy make it far more than a simple documentary. While perhaps niche, its earnestness and insight are undeniable, offering a rewarding experience for anyone interested in theatre, film, or the artistic process itself. It remains a compelling argument that the right approach can make even centuries-old texts feel immediate and alive. What lingers most is Pacino's insistent question, echoing long after the credits: Why shouldn't this belong to everyone?