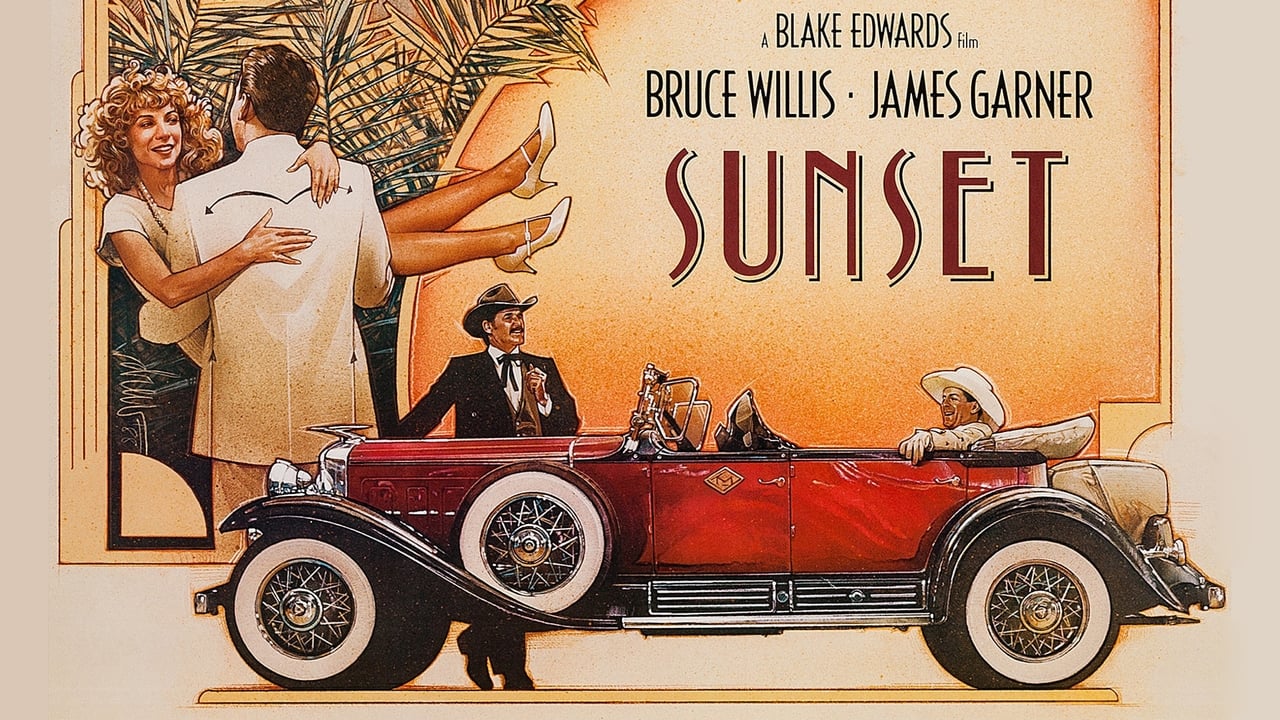

It's a strange kind of twilight the film casts, isn't it? That peculiar intersection where historical figures walk through the fabricated landscapes of memory and myth. Sunset (1988) arrives with such a tantalizing premise: the legendary lawman Wyatt Earp, aged but still formidable, navigating the gaudy, nascent dream factory of 1929 Hollywood alongside the era's biggest Western movie star, Tom Mix. The very idea evokes a certain wistfulness, a collision of American archetypes under the California sun, promising a reflection on authenticity and artifice.

Ghosts in the Dream Factory

The film immediately establishes a mood that’s less rollicking adventure and more elegiac noir, filtered through the lens of late-era Blake Edwards. Known primarily for his masterful touch with comedy (The Pink Panther, Victor/Victoria), Edwards here attempts something decidedly more complex, weaving a murder mystery into this tapestry of historical fiction. The air hangs thick with the scent of orange groves and corruption, a Hollywood on the cusp of sound, where fortunes are made and secrets buried with equal speed. Henry Mancini, Edwards' indispensable collaborator, provides a score that underscores this duality – tinged with jazz-age melancholy and occasional bursts of Western fanfare, it perfectly captures the film's often uneasy blend of tones. It’s a score that feels less like accompaniment and more like an atmospheric guide through this gilded, shadowed world.

A Tale of Two Icons

At the heart of Sunset are its two leads, embodying the film's central conceit. James Garner, bringing his innate charm and weary integrity, portrays Wyatt Earp not as the quick-draw hero of legend, but as an aging consultant, a living relic observing the celluloid mythmaking that would soon supplant his reality. Garner, no stranger to iconic Western roles himself (most notably Maverick), lends Earp a quiet dignity and understated authority that feels utterly authentic. There's a weight in his performance, a sense of a man who has seen too much, now bemusedly navigating a world obsessed with image. It’s a portrayal steeped in lived experience, far removed from simplistic heroism.

Playing opposite him is Bruce Willis as Tom Mix. Caught in that fascinating moment between TV's Moonlighting ending and Die Hard cementing his action-star status (though Die Hard actually hit theaters before Sunset), Willis tackles the role of the charismatic, perhaps naive, silent film cowboy with gusto. He captures Mix’s screen persona – the flashy smile, the performative swagger – while hinting at the man beneath the ten-gallon hat, drawn into a dangerous game far removed from his scripted heroics. The chemistry between Garner and Willis is palpable, a believable rapport between the seasoned veteran and the matinee idol, grounding the film even when the plot strains credulity.

Retro Fun Fact: While the film depicts a close working relationship and friendship forged during the murder investigation, the real Wyatt Earp and Tom Mix likely only knew each other peripherally, if at all. Earp did spend his final years in Los Angeles and served as an unpaid technical advisor on some early Westerns, offering filmmakers firsthand accounts of the Old West. Mix, a pallbearer at Earp's funeral in 1929, was indeed a colossal star. The film's central narrative, however, is pure invention, a fascinating "what if?" scenario crafted by Edwards.

Shadows Beneath the Tinsel

The plot itself revolves around the murder of a brothel madam, pulling Earp and Mix into the orbit of the menacingly decadent studio head Alfie Alperin, played with silky villainy by Malcolm McDowell. It’s here that Edwards leans into noir conventions: dark secrets, powerful figures operating above the law, and a pervasive sense of moral ambiguity lurking beneath the glamorous surface. The film explores themes of manufactured identity, the corrupting influence of power, and the often-brutal reality hidden by Hollywood's carefully constructed facade. How much of the heroic West was real, and how much was already a performance, even before Mix recreated it on screen? The film doesn't offer easy answers, preferring to let the questions linger in the hazy California light.

Retro Fun Fact: The production aimed for period accuracy, recreating the look and feel of late 1920s Hollywood, from the studio backlots to the opulent mansions. However, this ambition came at a cost. Budgeted at a respectable $16-19 million, Sunset unfortunately failed to connect with audiences, grossing a mere $4.6 million domestically. Critics were largely unkind, often pointing to the film's uneven tone – caught somewhere between comedy, mystery, Western, and character study – as a key weakness.

An Ambitious Misfire?

Looking back, Sunset feels like an ambitious experiment, a film perhaps too idiosyncratic for its time. It defied easy categorization, which likely contributed to its commercial failure. It even earned Blake Edwards a Razzie Award for Worst Director, a stark indicator of its troubled reception (co-star Mariel Hemingway also won Worst Supporting Actress). Yet, there's a distinct, melancholic charm to it. The central performances by Garner and Willis remain compelling, carrying a weight and nuance that elevates the material. The film's atmosphere is thick and evocative, and its core idea – the meeting of the real West and the reel West – retains a potent fascination.

Perhaps Sunset is best viewed not as a failed comedy or a straightforward mystery, but as a reflective, slightly surreal mood piece about the ghosts of American myth and the seductive, often dangerous, power of the Hollywood dream machine. What does it say about our relationship with legends, both historical and cinematic? How does the passage of time reshape our understanding of these figures?

VHS Heaven Rating: 6/10

Justification: While the uneven tone, sometimes languid pacing, and underdeveloped mystery prevent Sunset from being a true classic, the superb performances from James Garner and Bruce Willis, Henry Mancini's evocative score, the unique central concept, and the richly realized period atmosphere grant it significant merit. It’s a fascinating, flawed film whose ambition is palpable, even if its execution falters. The 6 reflects its strengths in performance and concept, balanced against its narrative and tonal inconsistencies.

Final Thought: Sunset remains a curious artifact of late 80s Hollywood – a film that tried to blend genres and eras with mixed results, but offers a uniquely melancholic reflection on fame, history, and the powerful illusions crafted under the California sky. It’s the kind of film you might have rented on a whim, drawn by the stars, only to find something stranger and more thoughtful than expected.