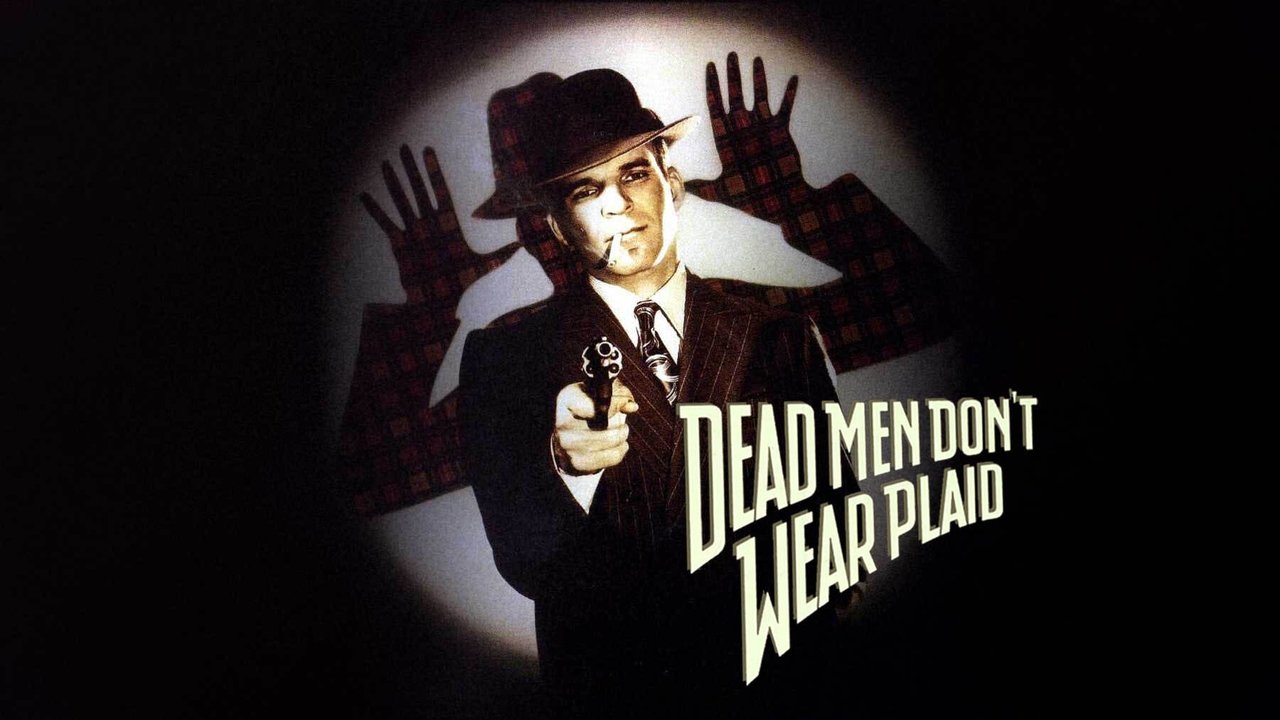

Okay, slide that beat-up copy of The Maltese Falcon to the side for a second. Remember digging through the comedy section at the video store, past the usual stand-up specials and broad slapstick, and finding that black and white box? The one with Steve Martin looking impossibly cool, aiming a heater, surrounded by ghosts of Hollywood past? Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid (1982) wasn't just another comedy; it felt like stumbling onto a secret handshake between the goofball 80s and the smoky, cynical world of 40s film noir. And watching it again now? It's still unlike anything else.

The premise alone is pure, high-concept genius sparked by director Carl Reiner (coming off hits like The Jerk with Martin) and co-writers George Gipe and Martin himself. Private eye Rigby Reardon (Steve Martin, naturally) is hired by the stunning Juliet Forrest (Rachel Ward) to investigate the suspicious death of her father, a renowned cheesemaker. What unfolds is a plot so convoluted it makes The Big Sleep look like a nursery rhyme, but the real magic trick? Rigby interacts directly with characters from nineteen genuine film noir classics. We're talking Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, Ingrid Bergman, Burt Lancaster, Barbara Stanwyck – the absolute titans – seamlessly woven into Rigby's investigation.

### A Gumshoe Walks Into A Dozen Movies

Forget CGI trickery; this was old-school movie magic, the kind that required painstaking planning and flawless execution. The sheer audacity of writing a coherent (well, comedically coherent) story around pre-existing dialogue and scenes from Golden Age Hollywood is mind-boggling. Think about it: they had to script Martin's lines and reactions to perfectly match snippets of dialogue recorded decades earlier. It’s a testament to the writers’ ingenuity and Martin’s pitch-perfect performance. He doesn't just react; he inhabits the noir world with a brilliant blend of hardboiled cool and his signature physical absurdity. Watching him get driving directions from Alan Ladd or tough advice from Bogart never gets old. My well-worn tape of this always seemed to pause best right when Rigby was getting inadvertently insulted by someone who filmed their lines 40 years prior.

The film's technical brilliance extends beyond the concept. Cinematographer Michael Chapman (Raging Bull, Taxi Driver) masterfully shot the new footage in stark black and white, meticulously matching the lighting, camera angles, and even the film grain of the classic clips. This wasn't just slapping Martin into old movies; it was recreating the feel of noir so precisely that the seams barely show. The editing, by the legendary Bud Molin (a frequent Reiner collaborator), is the unsung hero, weaving these disparate pieces into a functional narrative tapestry. It must have been an absolute nightmare in the editing bay, trying to sync up Martin’s reactions with Cagney’s threats or Lancaster’s pronouncements.

### Martin, Master of Mock Noir

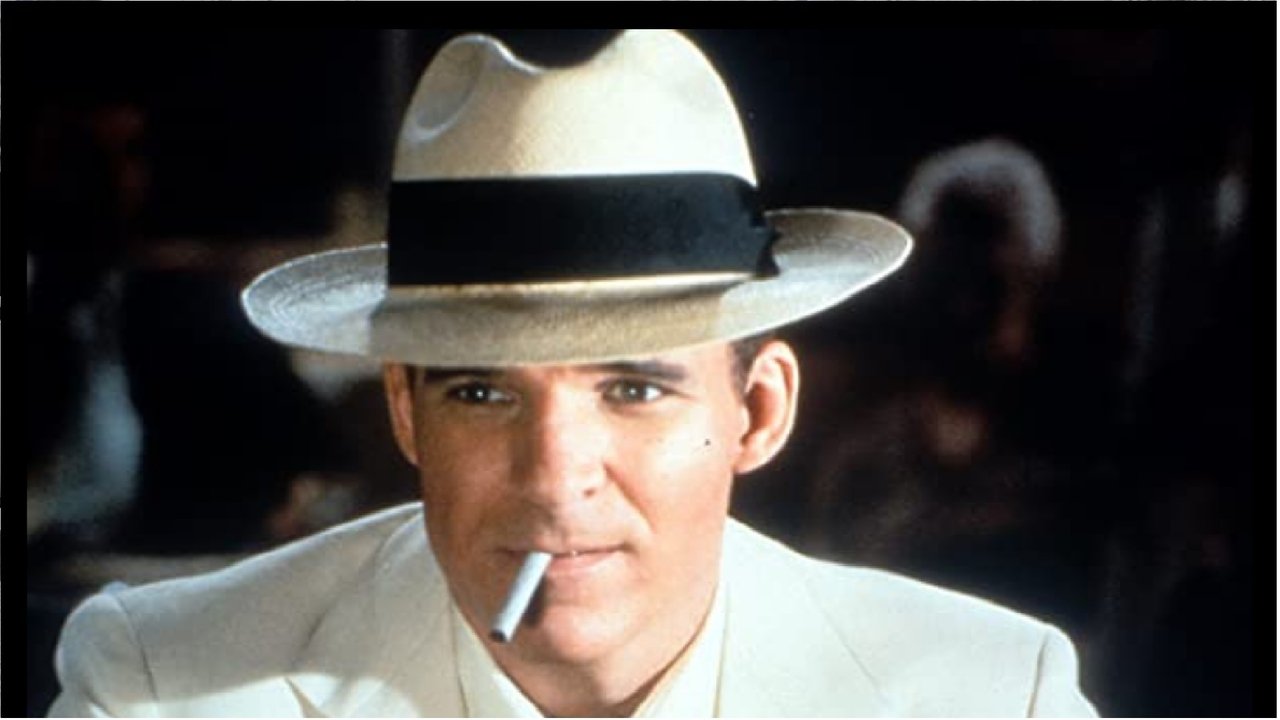

And then there's Martin. This film hit during his white-hot streak, transitioning from "wild and crazy guy" stand-up to versatile movie star. His Rigby Reardon is a masterclass in parody. He plays the tough-guy tropes straight enough to fit the noir aesthetic but injects just enough modern absurdity and physical comedy (like his ridiculously drawn-out bullet wound reaction or the infamous "cleaning woman" scene) to keep it hilarious. Remember how convincing those bullet hits looked back then, even in parody? Martin sells the exaggerated pain with gusto. Rachel Ward, fresh off Sharky's Machine, embodies the femme fatale archetype beautifully, playing the perfect foil to Martin's antics while radiating genuine Golden Age glamour. Let's not forget the legendary Edith Head designed the costumes – her final film credit, earning her a staggering 35th Oscar nomination. She absolutely nailed the period look.

Behind the scenes, securing the rights to use clips from all those iconic films (from multiple studios!) was apparently a Herculean task in itself, a testament to the producers' dedication. The film had a decent budget for the time, around $9 million, and while it wasn't a runaway blockbuster (grossing about $18.2 million), it found its audience – especially among film buffs who could appreciate the deep cuts and cinephile jokes woven throughout. Critics generally admired the cleverness, even if some found the central gimmick wore thin. But for those of us huddled around the CRT glow? It was pure gold.

### Still Sharper Than a Clean Bullet Wound

Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid works because it’s crafted with genuine affection. It’s not just mocking film noir; it's celebrating it, using its tropes as a playground for Martin’s unique comedic talents. The integration of classic footage feels less like a gimmick and more like an incredibly elaborate, loving homage. It's a time capsule – capturing both the glorious cynicism of 40s noir and the inventive absurdity of early 80s comedy.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the sheer technical achievement, Steve Martin's comedic brilliance perfectly suited to the role, and the film's enduring unique charm. It’s a masterclass in high-concept execution, blending parody and homage with incredible skill. While its plot is intentionally nonsensical, the joy comes from watching the impossible happen on screen.

Final Thought: In an age of seamless digital manipulation, there's a special kind of magic to Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid's analogue ingenuity – a reminder that sometimes the cleverest tricks were pulled off with scissors, glue, and pure cinematic love. It's still dazzlingly inventive today.