It begins with an ending, doesn't it? The mournful sound of a lone bugle playing "Taps," a melody intrinsically linked with finality, with honor paid at the close of day or the close of life. That haunting sound permeates Harold Becker's 1981 drama, Taps, a film that burrowed under my skin when I first slid that hefty cassette into the VCR decades ago, and still resonates with a disquieting solemnity upon revisiting. It poses a stark question right from the outset: What happens when dedication curdles into fanaticism, when the ideals meant to build character become the very walls of a prison?

### The Last Stand at Bunker Hill

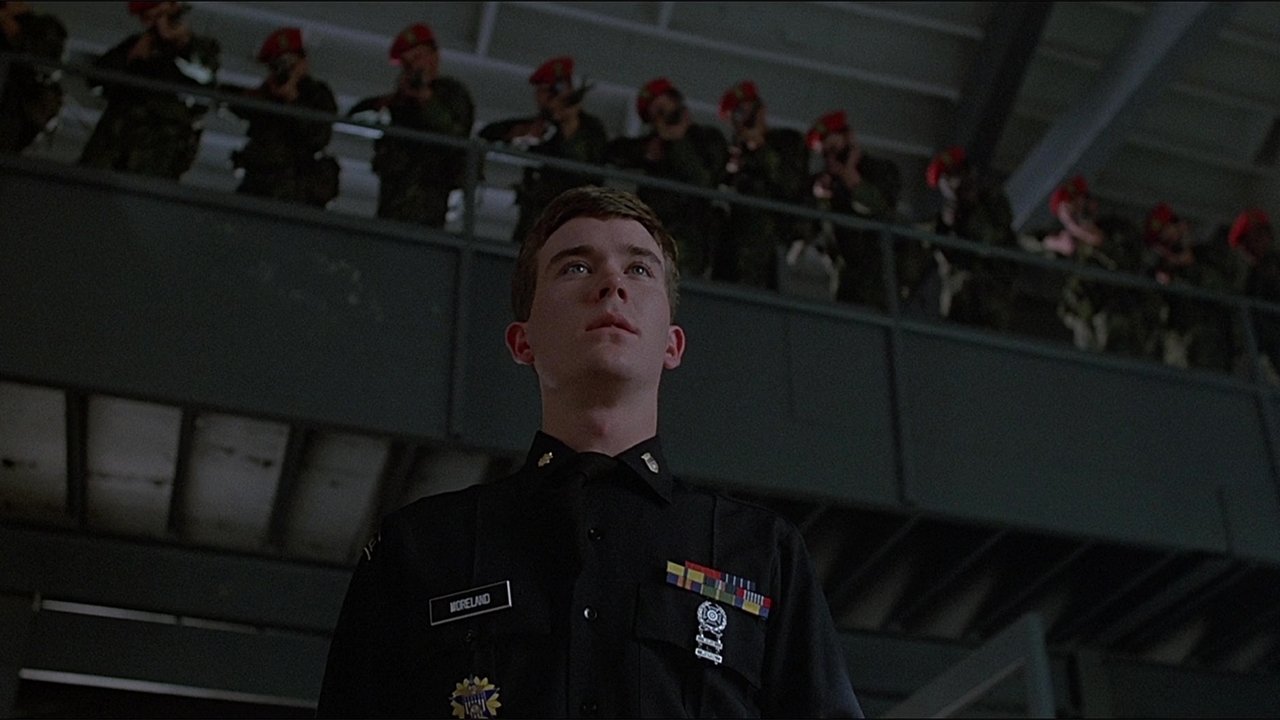

The setting is the venerable Bunker Hill Military Academy, a bastion of tradition seemingly untouched by the changing world outside its stone gates. But change is coming. The institution, deemed financially unviable, is slated to be sold to developers. For Cadet Major Brian Moreland (Timothy Hutton) and his fellow cadets, this isn't just losing a school; it's the desecration of a sacred way of life, embodied by the academy's stern but respected commanding officer, General Harlan Bache (George C. Scott). When a tragic accident involving Bache and local townies escalates, Moreland, driven by a fierce, almost terrifying sense of honor instilled by the General, makes a fateful decision: the cadets will seize the armoury, secure the campus, and hold Bunker Hill against the outside world until their demands are met. What starts as a principled stand rapidly spirals into something far more dangerous.

### A Crucible of Young Talent

Taps is notable today perhaps as much for the confluence of young talent it showcased as for its narrative. Timothy Hutton, fresh off his poignant, Oscar-winning turn in Ordinary People (1980), carries the film's considerable weight. He embodies Moreland's journey from dutiful cadet leader to the burdened, increasingly isolated commander of a doomed cause. You see the conflict warring within him – the unwavering belief in Bache's code clashing with the horrifying practicalities of armed standoff. It’s a performance etched with a kind of tragic gravity.

And then there are the electrifying screen debuts of Sean Penn as Alex Dwyer, Moreland's pragmatic but loyal second-in-command, and a young Tom Cruise as the chillingly intense Cadet Captain David Shawn. Penn already radiates that coiled energy, the spark of rebellious intelligence questioning the escalating madness. Cruise, in a role reportedly expanded because he impressed director Becker so much during auditions, is utterly riveting as the cadet who embraces the military aspect with terrifying zeal. His portrayal of Shawn, eyes burning with conviction even as he advocates for deadly force, is an early, startling glimpse of the screen presence that would define his career. Seeing these three together, so young and brimming with raw potential, feels like witnessing the birth of future Hollywood titans within the tense confines of the academy grounds. Their commitment was palpable; stories circulated about Penn and Cruise, in particular, remaining intensely focused, almost living their roles during the shoot at the very real Valley Forge Military Academy and College in Pennsylvania, which lends the film an undeniable layer of authenticity.

### The Weight of Tradition

Beyond the performances, Taps succeeds in creating a specific, almost claustrophobic atmosphere. Becker, who would later helm thrillers like Sea of Love, directs with a steady, unflashy hand, letting the tension build organically. The film, adapted by Darryl Ponicsan (whose previous work like The Last Detail explored military life's absurdities and anxieties) and Robert Mark Kamen (future scribe of The Karate Kid), doesn't shy away from the seductive power of military tradition – the crisp uniforms, the precision drills, the unwavering code of honor. But it also interrogates it ruthlessly. George C. Scott, radiating the same authoritative command he brought to Patton, serves as the embodiment of this tradition. Bache isn't depicted as a villain, but as a figure whose deeply ingrained beliefs, passed down to impressionable young men, inadvertently sow the seeds of tragedy. His personal code, noble in his eyes, proves dangerously inflexible in the modern world. Is unwavering adherence to tradition always virtuous, the film seems to ask, or can it become a blinding, destructive force?

### Echoes in the Corridor

Watching Taps today evokes a particular kind of nostalgia – not just for the actors or the era, but for a certain type of earnest, issue-driven studio drama that feels less common now. It’s a film that takes its themes seriously, perhaps bordering on ponderous at times, but its commitment is admirable. The central conflict – youth idealism crashing against adult compromise and the harsh realities of consequence – remains potent. The practical effects, the tangible weight of the weapons and the academy itself, feel grounded in a way that CGI spectacle often lacks. The film's $14 million budget yielded a respectable $35.9 million at the box office, finding a solid audience, particularly as a staple on video store shelves – that well-worn tape felt heavy in the hand, mirroring the film's thematic load. The very title, invoking the somber bugle call, hangs over the proceedings, a constant reminder of the potential cost of the cadets' stand.

There's a profound sadness that lingers after the credits roll. It's the sadness of potential squandered, of innocence lost not through external corruption, but through an excess of misplaced virtue. It forces a reflection on how easily noble intentions can pave the road to disaster, especially when guided by rigid ideology rather than adaptable wisdom. What remains more powerful than any single scene is the collective portrait of boys forced into the crucible of manhood too soon, armed with weapons they barely understand and ideals they tragically misapply.

Rating: 7.5/10

Justification: Taps earns its score through its powerful central performances, particularly from the young trio of Hutton, Penn, and Cruise, and the gravitas provided by Scott. Its exploration of complex themes like honor, tradition, and the dangers of extremism is compelling and thought-provoking. The authentic location shooting and Becker's steady direction create a palpable atmosphere. However, it can feel slightly heavy-handed or slow in places, and the earnestness occasionally tips towards melodrama. Despite this, it remains a potent and memorable drama from the era.

Taps doesn't offer easy answers, leaving you instead with the haunting echo of that bugle call and the unsettling image of youthful conviction tragically hardening into something brittle, and ultimately, breakable. It’s a film that stays with you, a quiet testament to the perils of taking principles to their breaking point.