The lights flicker. A grainy image resolves on the CRT screen – the unmistakable, decaying grandeur of a future Manhattan transformed into the ultimate penitentiary. It's 1997, as envisioned by 1981, and the air crackles not just with static, but with the palpable dread and cynicism that John Carpenter, already a master of tension after Halloween (1978) and The Fog (1980), bottled so perfectly in Escape from New York. This isn't just a movie; it's a mood, a grimy prophecy delivered on magnetic tape, a film that felt dangerous and thrillingly plausible late at night in a darkened living room.

Welcome to the Jungle, Pal

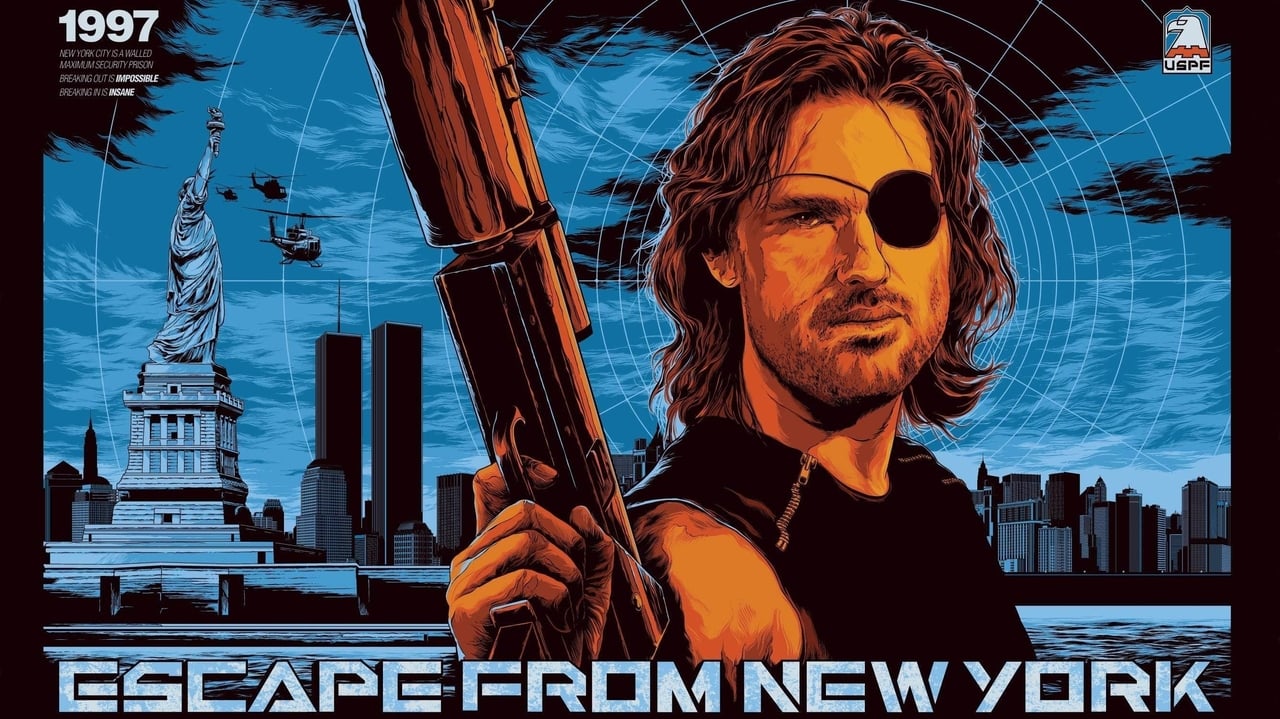

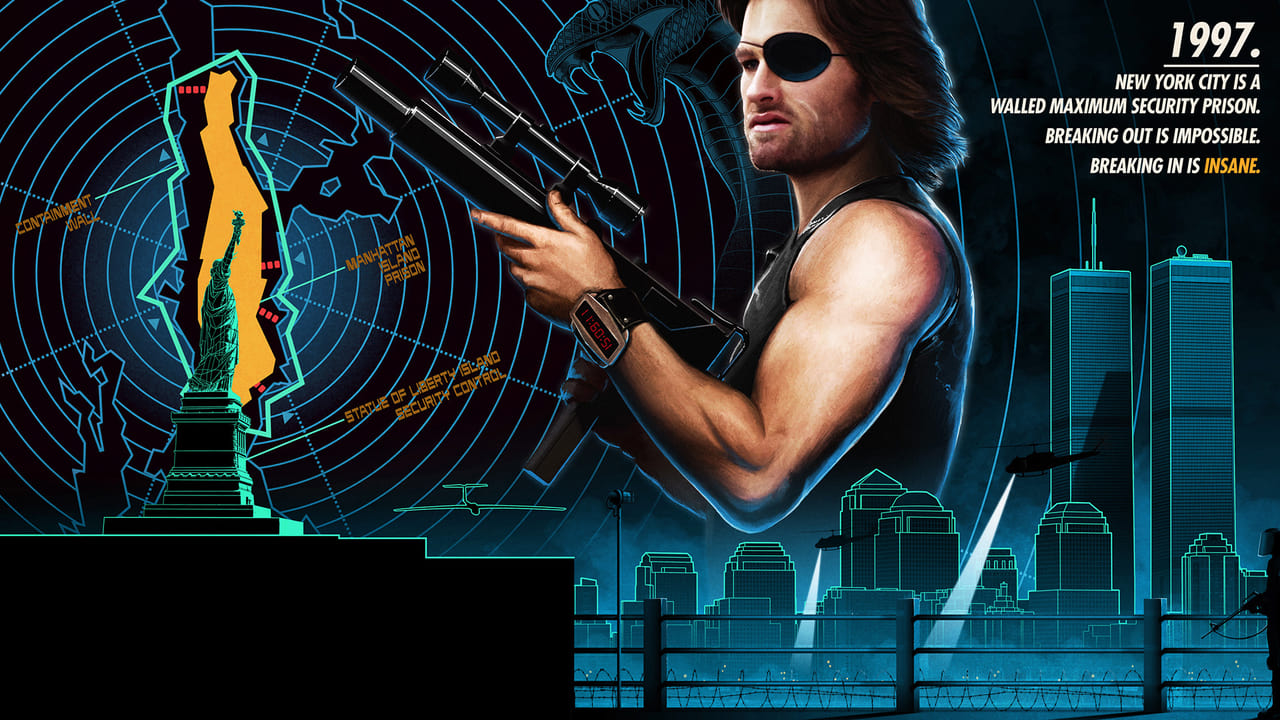

The premise is elegantly simple, brutally effective: Air Force One is downed over the maximum-security island prison of Manhattan. The President of the United States (a perfectly cast Donald Pleasence) is lost somewhere in the urban wilderness, held hostage by the inmates. The clock is ticking – a vital peace summit hangs in the balance. Who do you send into this hellhole? Not a hero. Not a team. You send the baddest man available: notorious bank robber and war hero-turned-criminal, Snake Plissken. Kurt Russell, shedding his Disney image with venomous glee, becomes Snake. The eye patch, the perpetual scowl, the weary resignation – it wasn't just a role; it was the birth of an instant anti-hero icon, a figure whose cynical cool resonated deeply in an era wrestling with disillusionment. Remember how effortlessly badass he seemed, even with microscopic explosives ticking away in his neck?

Carpenter’s genius here lies in the world-building, achieved with remarkable economy. He doesn't over-explain. We feel the decay, the desperation, the tribal savagery that has overtaken the city. The darkness is oppressive, punctuated by flickering fires and the eerie glow of makeshift encampments. This wasn't shot in a gleaming studio backlot version of dystopia. Carpenter, ever resourceful, famously utilized parts of St. Louis, Missouri, specifically areas ravaged by a massive fire in 1977, providing incredibly authentic, large-scale urban decay on a relatively meager $6 million budget. Those haunting cityscapes felt disturbingly real, enhancing the feeling that society was truly teetering on the brink.

A Symphony of Urban Decay

The atmosphere is thick enough to choke on, amplified by Carpenter's own iconic, minimalist synthesizer score (composed with Alan Howarth). Those pulsing, repetitive themes became synonymous with Snake's journey, underlining the tension and the isolation. It’s a score that burrows into your subconscious, as integral to the film's identity as the decaying sets or Plissken's sneer. The supporting cast, too, feels perfectly etched into this grim tapestry. Lee Van Cleef as Police Commissioner Bob Hauk embodies weary authority, his grudging respect for Plissken palpable. Ernest Borgnine brings a surprising warmth as Cabbie, a relic of the old world navigating the new chaos. And then there's Isaac Hayes as The Duke of New York, "A-Number-One," cruising through the ruins in his chandelier-adorned Cadillac – a flamboyant counterpoint to Snake's stripped-down survivalism. Each performance adds texture to this vision of societal collapse.

It's fascinating to remember the hurdles. The studio, Avco Embassy Pictures, wasn't initially sold on Kurt Russell, pushing for established tough guys like Charles Bronson or Tommy Lee Jones. Carpenter, who had previously worked with Russell on the TV movie Elvis (1979), had to fight hard for his choice, correctly sensing Russell's potential to embody Snake's unique blend of grit and charisma. Another fun fact often shared amongst fans: the opening narration and the coolly detached voice of the prison computer? That was an uncredited Jamie Lee Curtis, returning the favour after Carpenter launched her career in Halloween. These little details enrich the lore of a film made with grit and ingenuity.

Through the Grime and the Grain

Watching it again on a worn VHS copy (or, okay, maybe a slightly cleaner digital version these days) still hits differently. The practical effects, the matte paintings by artists like James Cameron (yes, that James Cameron, who worked as a special visual effects photographer and matte artist early in his career), the reliance on actual locations rather than sterile CGI – it all contributes to a tactile sense of reality, even within its fantastical premise. Sure, some elements might look dated to modern eyes accustomed to seamless digital wizardry, but there's an undeniable charm and weight to the practical craftsmanship. Doesn't that slightly clunky glider sequence still feel nail-biting precisely because it looks so precarious?

The film wasn't just an action romp; it tapped into post-Watergate, post-Vietnam anxieties, presenting a future where authority was compromised and survival depended on cynical pragmatism. Snake wasn't saving the President out of patriotism; he was saving his own skin. That resonated. Escape from New York felt less like escapism and more like a grim reflection, albeit through a pulpy, B-movie lens. Its influence is undeniable, echoing in countless dystopian films and famously inspiring Hideo Kojima's Metal Gear Solid video game series (Solid Snake owes a lot to Plissken). Even the less-loved sequel, Escape from L.A. (1996), further cemented Snake's cult status.

The Verdict

Escape from New York remains a high-water mark for John Carpenter and 80s sci-fi action. It’s lean, mean, atmospheric, and anchored by one of the most iconic anti-heroes in cinema history. The world-building is immersive, the score unforgettable, and the sheer audacity of the concept still thrills. While some effects betray their age, the film's gritty style, cynical heart, and Kurt Russell's star-making performance haven't aged a day. It perfectly captured a specific cultural mood and delivered a pure shot of dystopian cool that fans like us devoured back in the video store days. I distinctly remember the worn clamshell case being a permanent fixture near my VCR for a good while.

Rating: 9/10

Final Thought: Call him Snake. Decades later, this grimy, electrifying trip into the Big Apple prison still feels like essential viewing – a testament to Carpenter's vision and the enduring power of a great concept executed with style and swagger.